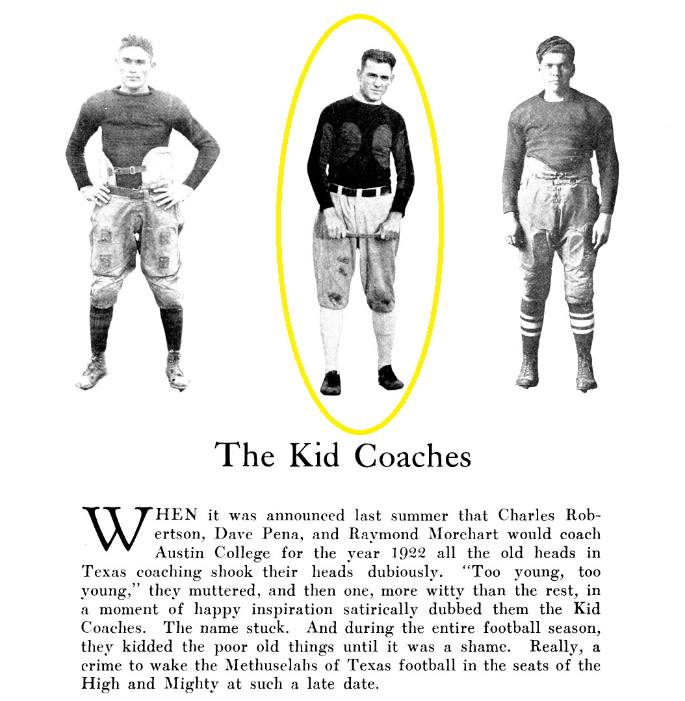

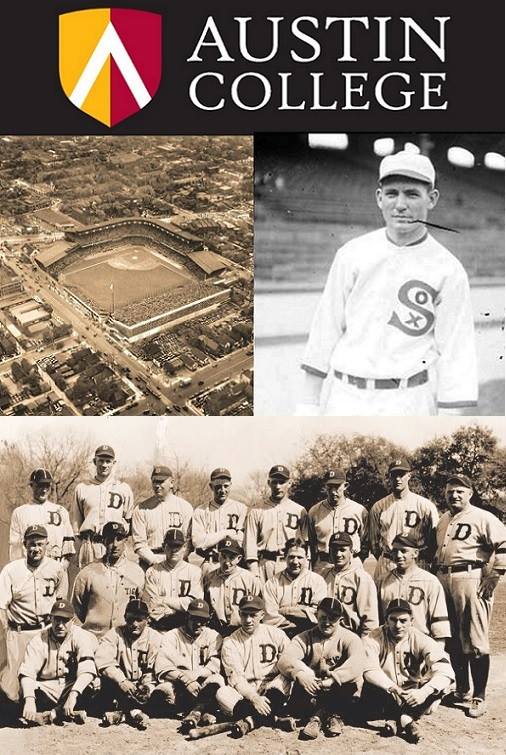

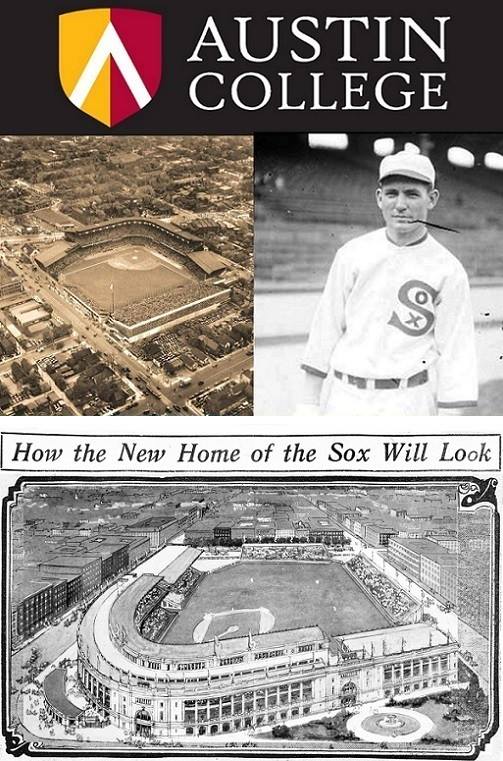

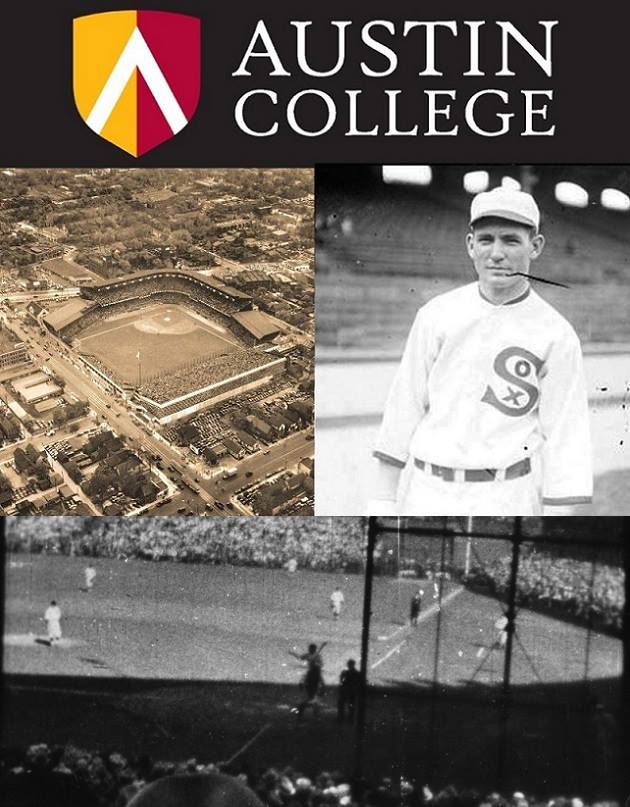

On May 13th, 1919, an Austin College Kangaroo pitcher made the lonely walk to the pitcher’s mound at Comiskey Park in Chicago.

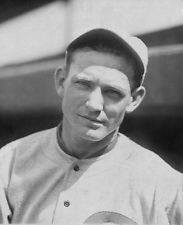

His name was Charlie Robertson. It was his first start ever for the Chicago White Sox.

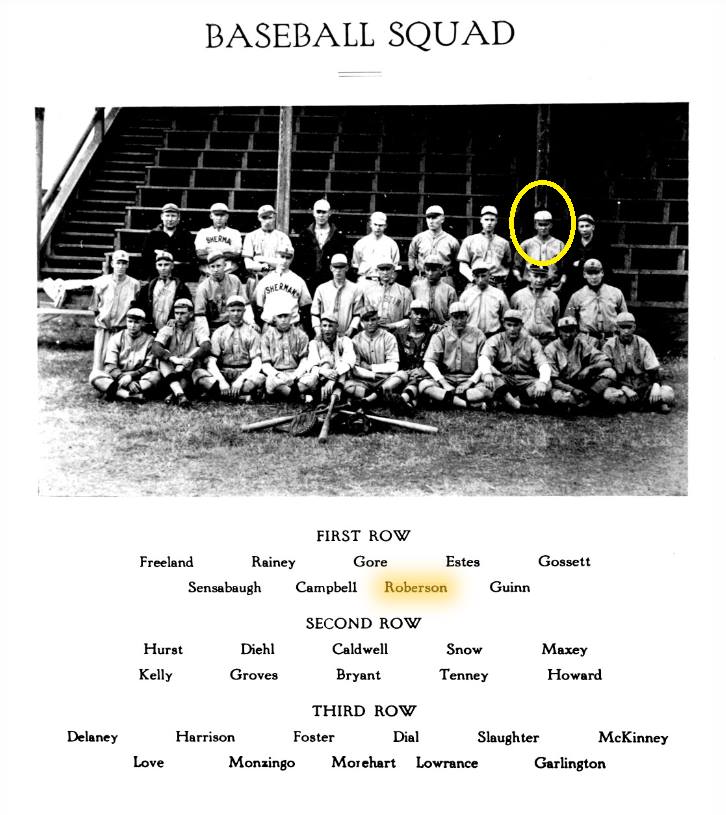

Robertson had graduated from Austin College in 1918. As a pitcher for the Kangaroos, he had faced the biggest schools in the state from Austin & College Station to Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, & Waco. Charles Comiskey’s club had shown enough interest to offer him a contract after Sherman, and Manager Kid Gleason had decided that May 13th would be Robertson’s rookie debut.

The 1919 White Sox were arguably the best team in the history of the franchise. Robertson had a lot of defense and power backing him up:

(1) Arnold “Chick” Gandil. First base. 1,176 hits over 9 years, and a member of the 1917 White Sox World Champion team. Gandil would go 2-for-4 at the plate on May 13th.

(2) Charles “Swede” Risberg. Shortstop. 394 hits over 3 years, and also a member of the 1917 championship team. Risberg would earn a walk and steal a base on May 13th.

(3) George “Buck” Weaver. Third base. A .272 batting average (BA) over 8 seasons with the White Sox, and also a member of the 1917 championship team. Weaver got a hit on May 13th.

(4) “Shoeless” Joe Jackson. Left Field. With a lifetime BA of .356 (3rd highest all time), Jackson is considered one of the best ever. He drew two walks, stole a base, and scored a run on May 13th.

(5) Oscar “Happy” Felsch. Center Field. Felsch’s 446 RBIs over five years with Chicago helped the White Sox earn the 1917 title. Felsch had a hit and stolen base on May 13th.

(6) Fred McMullin. Utility infielder. McMullin had seen action the day before and had reached first on a single. He’d spend May 13th watching Robertson from the dugout.

(7) Eddie Cicotte. Pitcher. Cicotte would pitch a four hit complete game shutout the next day. He cheered Robertson from the dugout on May 13th.

(8) Claude “Lefty” Williams. Pitcher. Williams had pitched a complete game shutout two days earlier. Alongside Cicotte, he would cheer Robertson from the dugout on May 13th.

All eight of these men would be banned from baseball after the 1919 season. The famous “Eight Men Out” were motivated by the selfishness, duplicity, and deceit of owner Charles Comiskey, and agreed to take bribes to throw the 1919 World Series. Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis, in an attempt to save the integrity of the game from gambling, banned all eight for life. No action was taken to address the unjust reserve clause, which created the conditions for the scandal in the first place.

The scandal is a century old this year, and is a part of American sports lore. The story is told in numerous books, and is remembered in the 1988 movie “Eight Men Out.” Risberg, Cicotte, Weaver, Gandil, and Shoeless Joe Jackson also appear in the 1989 movie “Field of Dreams.” In the movie, Jackson talks about the “thrill of the grass” and sadly notes that after the ban “I’d have played for nothing.” Kevin Costner’s character Ray Kinsella believes that if he builds it, Jackson will come. And he does, alongside others from the 1919 White Sox. At the end, Jackson reveals to Kinsella the actual person to which “he” refers.

In spite of the support that May day in 1919, Robertson lost a 2-1 decision to the St. Louis Browns. He gave up 5 hits, and was relieved by Dickey Kerr after two innings. Kerr, untainted by the Black Sox scandal, also appears in “Eight Men Out.”

The appearance at Comiskey for Robertson was a small taste of what was to come, a common path for rookie pitchers. After the loss, Robertson was sent down to the minors in Minneapolis. There, he watched the 1919 Black Sox scandal unfold from Minnesota. He also continued to work on his game.

By 1922, Robertson was called back up to the majors by White Sox player-manager Eddie Collins. Collins had been at second base on May 13th when Robertson headed to the mound. Like Kerr, Collins also had not been implicated in the Black Sox scandal.

The White Sox were in Michigan in late April of 1922, facing the Detroit Tigers at Navin Field (later renamed Tiger Stadium). Tiger Stadium, one of the most iconic ballparks in the game, was constructed in 1912 alongside Fenway and Wrigley; the stadium at Trumbull & Michigan remained in use by Detroit until 1999.

The 1922 Detroit Tigers were one of the best hitting teams in the history of the game; the year before, the Tigers had set an American League record by hitting an astounding .316 as a team. IT’S A RECORD THAT STILL STANDS TODAY. The 1922 Tigers were led by one of the best players to ever swing a bat. Ty Cobb’s lifetime batting average of .367 is tops in Major League history.

On April 30th, 1922, an Austin College Kangaroo pitcher made the lonely walk to the pitcher’s mound at Tiger Stadium in Detroit.

His name was Charlie Robertson. It was his third start ever for the Chicago White Sox.

He was asked to do something difficult. Beat the best hitting team in baseball. Maybe the best hitting team in the history of the game.

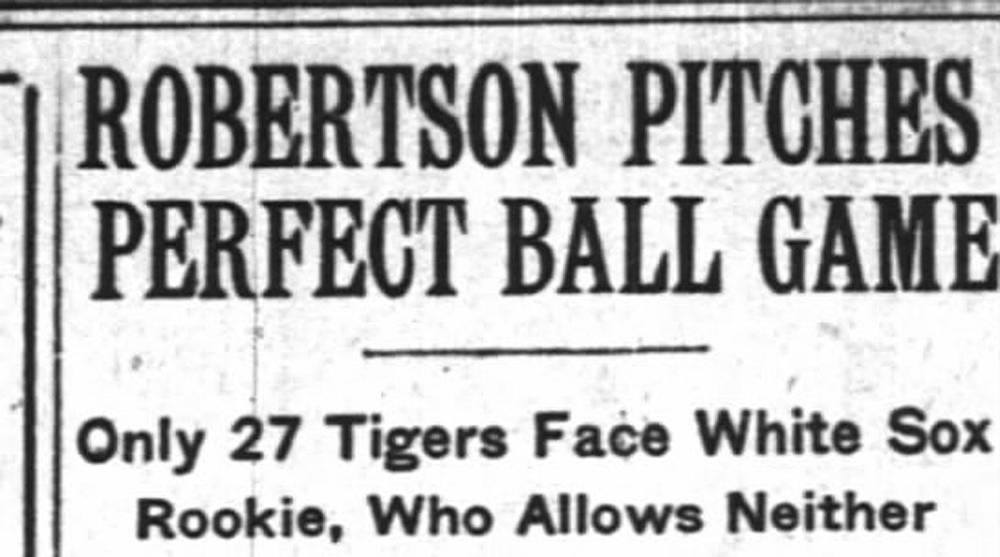

Robertson did them one better. He pitched a perfect game.

Wins, complete games, and shutouts are prized by pitchers. They occur with frequency. Rarer is the no-hitter, when an opposing team fails to record a single hit. But even no-hitters happen with some regularity. Nolan Ryan recorded seven no-hitters in his career, but never game close to the ultimate prize. The perfect game.

No hits. No walks. No errors. No one reaching first base. Perfection. In a game like baseball, when failing a majority of the time can still land you in the Hall of Fame, perfection is unattainable. And yet, over 118 years of modern Major League Baseball, it has happened. Since 1901, there have been roughly half-a-million pitching starts in the Majors. Only 21 of those ~500,000 starts have resulted in a perfect game. The odds of witnessing a perfect game at any random baseball game is 0.00008%. The odds of being struck by lightning? 0.0003%. You are four times more likely to get struck by lightning.

21 times. Only 21 times has a pitcher been perfect. And one of those perfectos was thrown on April 30th, 1922.

By an Austin College Kangaroo.

It’s the next Roo Tale, and it’s probably gonna be one of my favorites. It’s called:

“For Love of the Game: The Roo Tale of Charlie Robertson.”

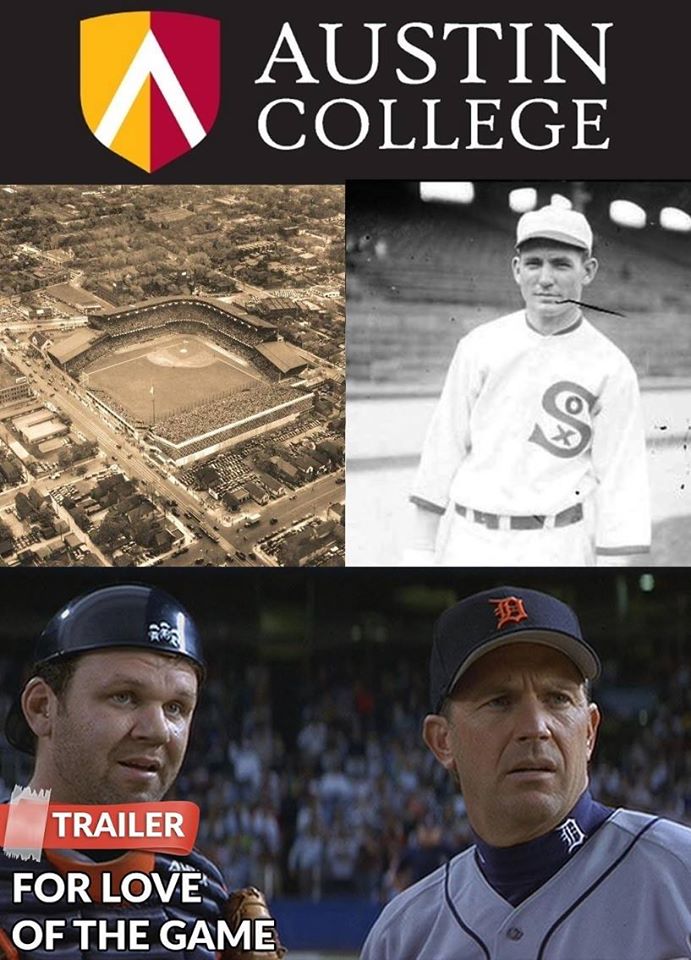

Kevin Costner is famous for his baseball movies. After “Field of Dreams,” he made another one in 1999 about a Detroit Tigers pitcher who throws a perfect game in his last major league start. His movie, “For Love of the Game,” has ties to this Roo Tale. Clips from the movie will be used to tell the story of Robertson’s perfect game.

There will be story previews every Saturday for the rest of January, the entire month of February, and early March. As winter turns to spring and we approach Opening Day, we’ll tell the story of Charlie Robertson’s incredible performance against the Detroit Tigers on that cold April day 97 years ago.

If it’s a baseball Roo Tale, then you better believe Imma gonna tag circa 1990 Roo baseball:

David Norman, Pat Rabjohn, Jason Willis, Shane Montgomery, Jimmy Baird, Phil Novicki, Rebecca Cannon Novicki, Ryan Nicholson, Pat Abernathey, Jamie Muro, Wayne Whitmire, Kelly Carver, B.k. May, Bj Wastoskie, Wes Tarbox (tag anyone I missed).

Should be a “perfect” winter of storytelling. See you next Saturday.

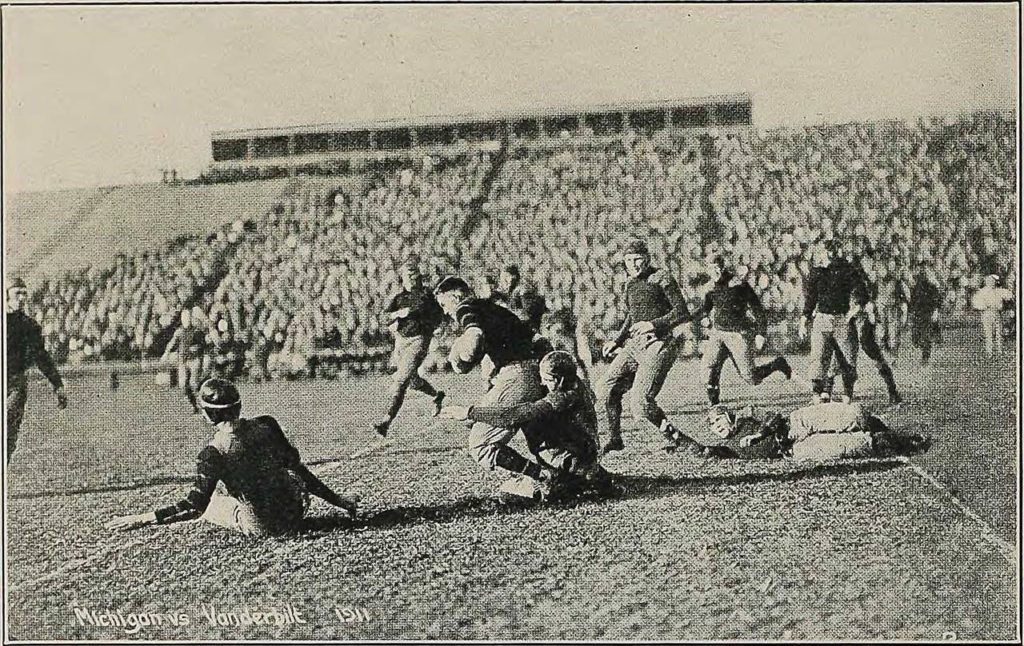

A

lot of great Roo Tales have occurred in the state of Texas. The best

one though, may just have taken place in the state of Michigan.

Michigan is the land of the Wolverines & the Spartans, the Lions

& the Tigers. It’s also the site of arguably the greatest moment in

Roo sports history. Charlie Robertson’s 1922 perfect game at Tiger

Stadium in Detroit.

Michigan is where American mobility was born;

Henry Ford and Walter Chrysler were both Michigan natives. It’s where

American battleground politics is often decided. There’s no Republican

more mainstream than former Wolverine football player Gerald Ford.

Michigan’s two Democratic Senators today are so boring you don’t even

know them.

The state has cities. There’s Detroit, and the

Motown culture gifted to the rest of America. The state has country.

The upper peninsula has a unique culture, and is far removed from

Lansing, Flint and points south.

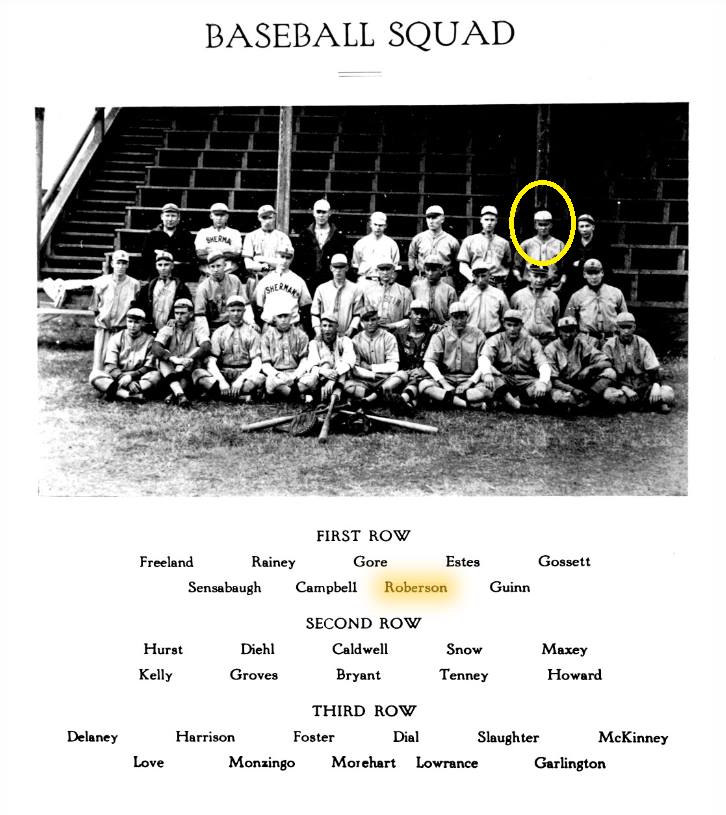

Michigan was the home of

Kangaroo Ray Morehart. The star Austin College second baseman’s

baseball path crossed with Charlie Robertson, both in Sherman and in

Michigan. Morehart spent the summer of 1922 playing minor league ball

in Flint, MI. That fall, he returned to coach Roo fooball in Sherman

alongside an already nationally famous Charlie Robertson. He was back

in Flint in 1923, where he caught the eye of the White Sox. In 1924,

Morehart was called up to the majors and became a teammate of Robertson

in Chicago.

The White Sox traveled to Tiger Stadium on

September 8th of 1924 for a three game series against Detroit. In game

#1, Morehart cheered his Roo teammate from the Chicago dugout as

Robertson returned to the scene of his perfect game two years earlier.

He pitched poorly, giving up 5 runs over 4 innings and earning the loss.

In game #2, they flipped roles. Robertson cheered his Roo teammate

from the Chicago dugout as Morehart was inserted into the lineup to give

the starting shortstop a rest. He went 0-for-4 with a walk in a

Chicago win at Tiger Stadium.

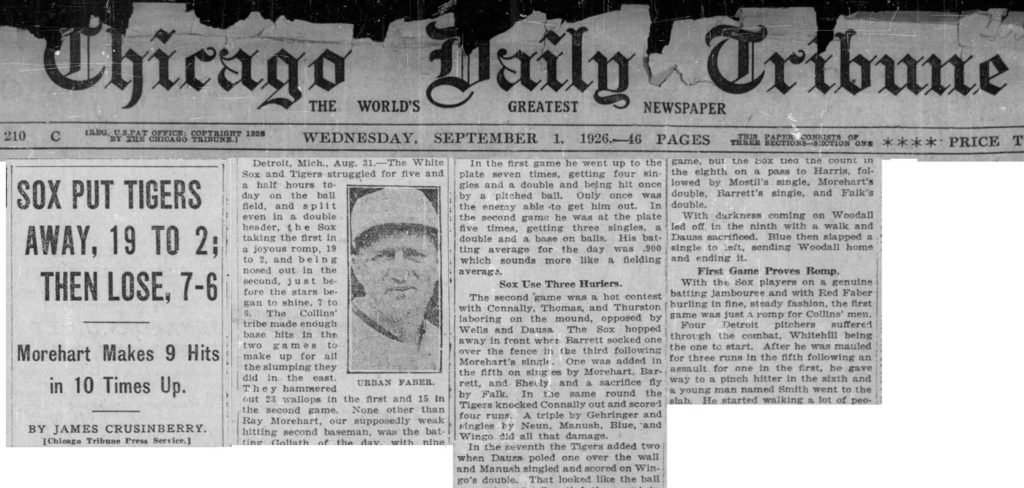

Morehart was back at Tiger

Stadium in 1926, and made history there on August 31st. That day, he

set a major league record that may never be broken. The White Sox were

in Detroit for a double header, and Morehart woke up that day ready to

play ball. From the Chicago Tribune:

“In the first game,

[Morehart] went up to the plate seven times, getting four singles, a

double, and being hit once by a pitched ball. In the second game, he

was at the plate five times, getting three singles, a double, and a base

on balls. His batting average for the day was .900, which sounds more

like a fielding average.”

That day, Ray Morehart had 9 hits for

the Chicago White Sox. Over approximately 25,000 days of major league

play spanning three centuries, no batter has ever had more hits on a

single day. The feat was done by a Roo……at Tiger Stadium.

The

1927 Yankees traded for Morehart, and the Kangaroo became a contributor

on arguably the best team in baseball history. New York traveled to

Detroit on July 8th, and beat the Tigers 10-8 at Tiger Stadium.

Morehart drove in a run, and scored twice: once on a Lou Gehrig single

and a second time on a Babe Ruth homerun.

But Michigan is not just the home of Roos long since departed. It’s also home for those of us in the land of the living.

Michigan is the land of the family of Susan Dworman-Oshinsky,

now a part of my own family. Susan grew up near Detroit in the shadow

of Tiger Stadium. She’s always ready to move back to Michigan during

every steamy summer in Houston. I told Susan about the story of Roo

Charlie Robertson’s perfect game in Michigan, and mentioned I’d give her

a shoutout. Here you go Susan, you’re in a Roo Tale now.

Michigan is the land of the family of Roo James Kowalewski. James married into a family of Michigan Wolverines, and headed with all of them to Atlanta last December for the College Football Hall of Fame sponsored Peach Bowl. There, he saw Austin College Coach Mel Tjeerdsma honored on the field for his 2018 induction. Go Blue, Christine Kowalewski, Go Blue.

Michigan holds the fandom of former Roo football team captain and coach Nathan Packard. Of the Wolverines, Nathan says “Michigan will always be my team. Win or lose. Go Blue!!!” Nathan’s spouse Sophie, a fellow Roo, may or may not bleed blue as much as Coach Packard. She’ll have to tell us.

Michigan is the former home of Maulyn Lynch and Jim Caffrey. Maulyn, a friend from my graduate school days and usually the smartest one in the room, calls Detroit one of her homes. Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy types travel quite a bit and have many homes. Jim, a friend from my days in Boston, is a Michigan Wolverine who recently ran for the Illinois House. I hope he throws his hat into the ring again.

Michigan is also the land of Andrea and Kyle Ward. Before her stint as the coach of Austin College softball, Andrea was a standout softball pitcher and coach in the Great Lakes state. Her family has a long history of playing and coaching in Michigan. She’s since moved from Sherman back to the Detroit area, having married into Kyle’s family of players and coaches.

When it came time to officially tie the knot last year, Andrea and Kyle did what any good former Roo coach would do. They called up AD David Norman & Margie Norman, asked them to get certified to perform a wedding, and fly up to Michigan. The Normans were soon on their way to the Detroit area, where Pastor David Norman performed a flawless ceremony. Roos marry Roos, you see.

Andrea mentions that “Kyle and I are defiantly Michigan [Wolverines] fans,” so they are probably familiar with Fielding Yost. Yost is the father of Michigan Wolverine football. He coached in Ann Arbor from 1901 to 1926, and built a program to rival the powers back east. His teams competed on campus at Ferry Field, today used for Wolverine track, soccer, and tailgating. Occasionally, they’d play at Detroit’s Tiger stadium, the site of Charlie Robertson’s 1922 perfecto. In 1911, the Wolverines played in Ann Arbor and took on another future Kangaroo.

Vanderbilt had one of its best teams ever in 1911. The Commodores finished the season with one loss, which came at the hands of Yost’s Wolverines at Ann Arbor. A photo of the 1911 Michigan-Vandy game survives, and shows a Wolverine tackling a Commodore running back at Ferry Field in front of thousands of fans. That running back is future Austin College Kangaroo football coach Ray Morrison.

Yost’s last gift to Michigan football came in his final year. With Ferry Field no longer sufficient to hold Wolverine football, Yost began work on the funds and construction needed for a new stadium. His creation, Michigan Stadium, is today a college football icon. Nicknamed “The Big House,” it’s the largest stadium in the United States. Broadcaster Keith Jackson, who passed away last week, was synonymous with Michigan Stadium; his call of Heisman winner Desmond Howard in 1991 is one Jackson’s most famous.

They play football in East Lansing too, just as they do in Ann Arbor. The Spartans have been suiting up since 1896, the same year that Austin College made it official. The golden age of Michigan State football occurred in the 1950s, when the Spartans won four national championships. Interestingly, one of the most famous Michigan State football alums made his name in baseball at Tiger Stadium.

Kirk Gibson was an All-American wide receiver for Michigan State and led the Spartans to a tie for the Big Ten Title. He was eventually elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 2017, just one year before Kangaroo Mel Tjeerdsma. Gibson, however, felt his calling was baseball. He was drafted by the Detroit Tigers organization in 1979. By 1984, he was a key member of one of the best Detroit Tigers teams in history.

Up 3 games to 1 in the 1984 World Series against the Padres, Detroit had a 5-4 lead in the 8th inning with two runners on. San Diego initially considered walking Gibson, but pitcher Goose Gossage wanted to go at Gibson. It was a huge mistake. Tiger Manager Sparky Anderson screamed “He don’t want to walk you” to Gibson, who launched a shot into the right field bleachers at the stadium where Charlie Robertson was untouchable. Detroit won the 1984 World Series, but has yet to win one since.

Like Michigan State, the glory years of the NFL’s Detroit Lions occurred in the 1950s. Led by Texas Longhorn Bobby Layne and SMU Mustang (and Claude Webb Jr. childhood hero) Doak Walker, the Lions won three NFL championships that decade. The 1953 championship was won in dramatic fashion against the Cleveland Browns. A Layne TD pass with seconds remaining tied the game at 16-16, and Doak Walker’s extra point sealed the championship for Detroit. Walker was the son of Austin College Kangaroo football star Ewell Walker; the 1953 championship game occurred at Charlie Robertson’s Tiger Stadium.

The Wolverines, Spartans, and Lions have all played at Tiger Stadium, and of course so have the Detroit Tigers. Tiger Stadium, built in 1912, was a baseball institution for decades. Located on the corner of Trumbull and Michigan, that stadium on “the corner” was just as much the icon as Wrigley or Fenway. In fact, I made a point to visit Tiger Stadium in 1993 on a baseball themed trip from Boston to Texas. I’m glad I did; the stadium where Robertson tossed his gem was torn down in 1999. I toured the place oblivious to Robertson’s feat, hopped back into my car, and headed for Wrigley and the Field of Dreams.

Tiger Stadium is no more, but the field remains. Today, the field where Robertson mowed down 27 Detroit Tigers is now known as “The Corner Ballpark,” run by the Detroit Police Athletic League (PAL). It’s open to the public every afternoon and used by various leagues in and around Detroit. I plan on making a second trip one of these days, so I can appropriately pay homage to Roo Charlie Robertson. Maybe I’ll plan something for April 30th, 2022, the 100th anniversary of his perfecto.

Or maybe I’ll just have Andrea Ward go on my behalf. Andrea, the former Roo softball coach married by the current Roo Athletic Director, is a Michigan native and huge Detroit Tigers fan. In fact, she visited the field after Tiger Stadium demolition and before the construction of “The Corner Ballpark.” She was kind enough to send me a photo. There she is, standing at the very spot where a furious Ty Cobb struck out in his last attempt to break up Roo Charlie Robertson’s perfect game. See the comments.

Thanks Andrea. Looking forward to meeting you and Kyle one of these days in the great state of Michigan.

More Charlie Robertson Saturday previews to come. See you next Saturday.

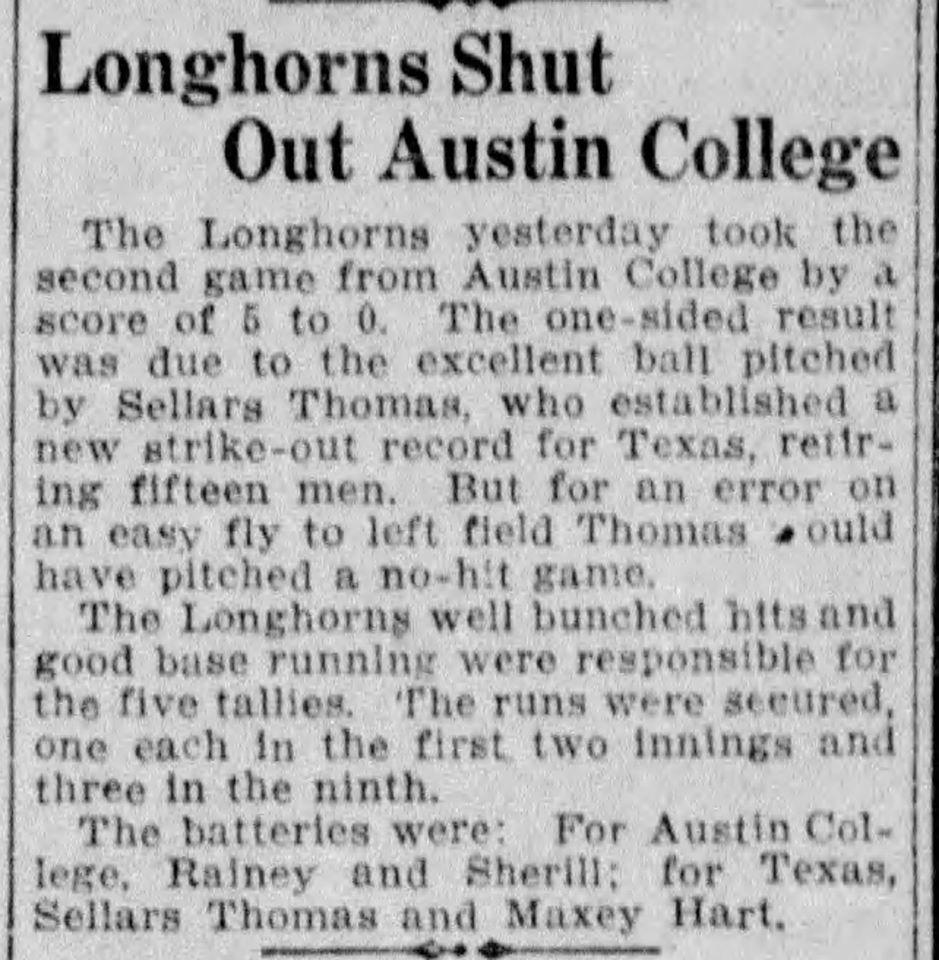

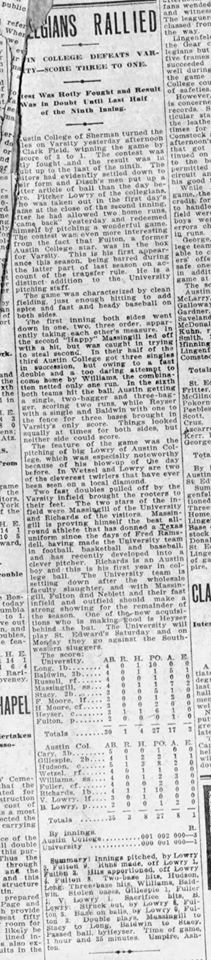

First year Longhorn manager Billy Disch was nervous. His 1911 Longhorns had gotten off to a poor 2-4 start, and were facing Austin College on the campus of the University of Texas. The Kangaroos had their ace pitcher set to start that March 30th afternoon, but Disch had his own ace as well……a transfer from Austin College. It didn’t matter. AC defeated the Longhorns 3-1 in a Roo-vs-former-Roo pitching duel, and returned to Sherman victorious over “Varsity.”

Billy Disch. Bibb Falk. Cliff Gustafson. Augie Garrido. From 1911 to 2016, Texas Longhorn baseball was managed by only these four men.

Billy Disch:

AC baseball before the birth of the Southwest Conference in 1914 enjoyed a golden era. Between 1908 and 1912, The Roos split 6 games with the Horns, and outscored UT 16-14. As the Billy Disch era began in earnest in Austin, that competition slowly came to an end. By the time of Disch’s retirement in 1939, the Horns had won 19 conference championships.

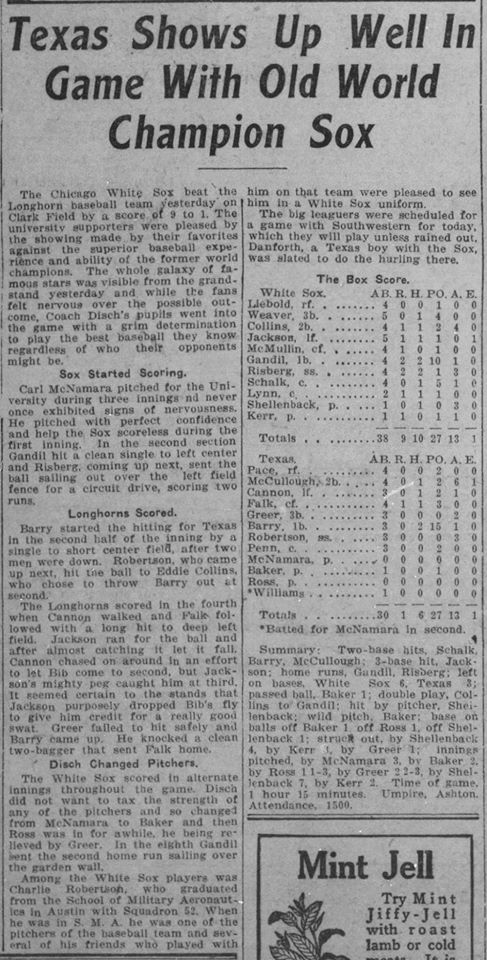

The year 1919 was one of those 19 championships. Disch’s Horns finished 1919 undefeated in conference play. They did suffer a loss in April however, when Kid Gleason’s Chicago White Sox came to Austin to face the Texas Longhorns. The 1919 White Sox were headed for the World Series that year, and 8 members of the team would be banned for life for throwing it. All 8 saw action that day. Shoeless Joe Jackson had one run on one hit, and Chicago easily beat Texas 9-1. The lone UT run was scored by Longhorn star Bibb Falk.

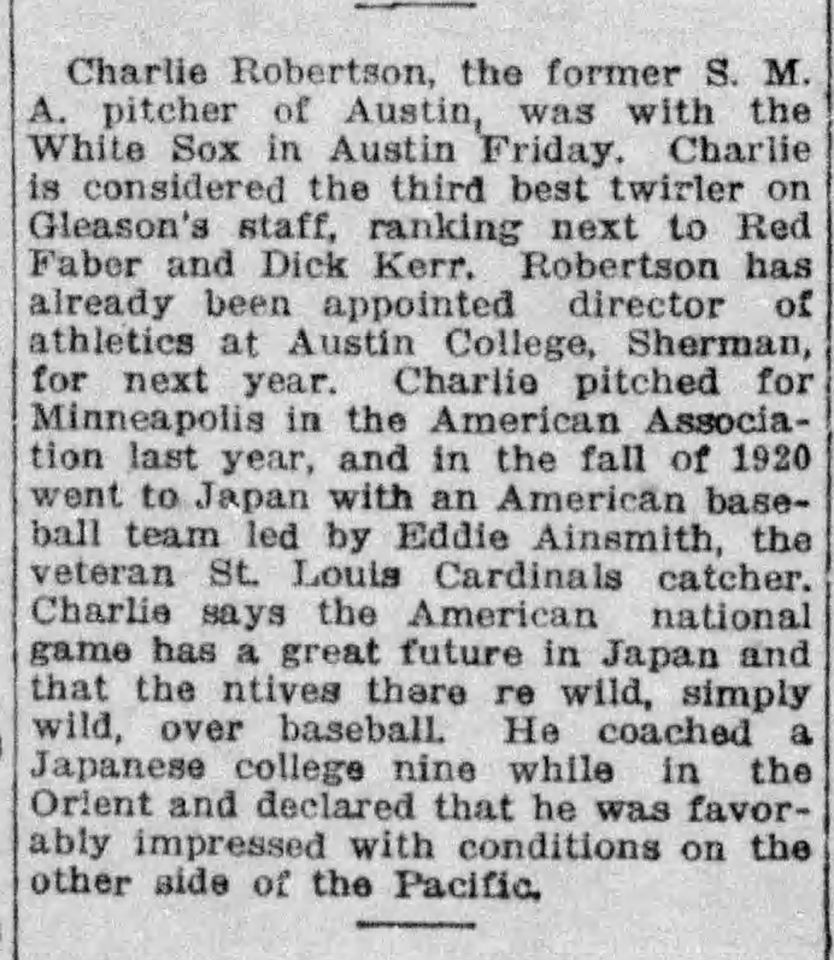

Austin College Kangaroo Charlie Robertson was also on the White Sox bench that day. The AC pitcher had been signed by Chicago just 10 days earlier, after two years of playing ball for the Roos in Sherman. After joining Comiskey’s squad, he boarded the team train in Dallas for the trip to Austin. The Austin American Statesman noted that “among the White Sox players was Charlie Robertson. He was one of the pitchers of the baseball team and several of his friends who played with him were pleased to see him in a White Sox uniform.” 1919 wouldn’t be the last time the paths of Kangaroo Robertson and Longhorn Falk would cross.

Eleven days later, the Longhorns had another opponent in Austin. Austin College was in town. The Roos had played competitive ball against the Horns in 1916, but 1919 was a different story. With Bibb Falk leading the way, the Horns won a two game series easily. Billy Disch had not scheduled the Roos in either 1917 or 1918, the only two years in which Charlie Robertson took the mound for Austin College. Smart move Mr. Disch, smart move.

Bibb Falk:

The 1919 Black Sox scandal banned the great Shoeless Joe Jackson from baseball, and Bibb Falk was signed by the White Sox in 1920 to be Jackson’s replacement in left field. Robertson, who was sent to the minors in 1920, was eventually called back up to Comiskey Park in 1922. That year, Robertson and Falk would be teammates in Chicago. Their 1922 season began in March, back in Texas. The White Sox were headed back to Austin again to face the Longhorns.

On March 24th, 1922, the White Sox again defeated the Horns on campus by a score of 8-4. Falk scored a run again, just as he had in 1919. Only this time, he scored for Chicago. Robertson, scheduled to start later that week in Houston against the minor league Buffaloes, watched his White Sox teammates defeat the Billy Disch’s Horns a second time from the dugout.

One month later, Robertson got his second start of the 1922 season in a White Sox uniform. On April 30th, he walked to the pitching mound at Tiger Stadium and proceeded to throw a perfect game against Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers. Falk, the starting left fielder for Chicago, had taken the day off. The final out of Robertson’s perfect game was caught by Falk’s replacement in left field.

Falk was picked to replace his former manager Billy Disch in 1939 at Texas, and ran UT baseball for nearly three decades. By 1967, Falk’s Longhorns had secured 19 conference championships and 2 national titles. UT’s new baseball stadium in 1975 was named Disch-Falk Field in honor of the Robertson White Sox teammate and his former Longhorn skipper.

Cliff Gustafson:

Falk was replaced with Cliff Gustafson in 1968. Over 28 years, Gustafson’s Longhorn teams secured 21 conference titles and won another two national crowns. Gustafson’s former players include such names as Roger Clemens, Calvin Schiraldi, Spike Owen, and Greg Swindell. That list also ALMOST includes Kevin Craig. Kevin is a colleague with me at UT System, and a fine ballplayer. He could have played nearly anywhere in the state, but he was a committed Longhorn. Kevin attempted to walk on at UT. He got the opportunity to show his stuff to Gustafson at Disch-Falk.

As I tell the story, his outfield throws were long, fast, and on target, but the throws of his competitors were just a bit longer and faster. Eventually, Gustafson put his arm around Kevin and said “you know, Texas Lutheran has a fine baseball program.” Kevin got the message; he knew that Longhorn baseball was just a bit out of reach. He’s been playing regularly in Austin for two decades, and his son is today an exceptional player on a UT-Dallas Comets baseball team that regularly competes for a D3 national title. The Comets play at Austin College this spring; Kevin and I may just head up to Sherman to watch.

Gustafson retired in 1996, and his legacy was just as rich as those left by Disch and Falk. Like his predecessors, he earned UT another 19 conference championships. Like Falk, he added another two national titles to the Longhorn resume. Gustafson was replaced in 1997 by a skipper who picked up exactly where his predecessors had left off.

Augie Garrido:

Augie Garrido had led Cal State Fullerton to three national titles between 1979 and 1995. To build the program, he often had to make some painful roster cuts. One of those who suffered the Garrido axe was an aspiring ballplayer named Kevin Costner. Like Kevin Craig attempting to make Gustafson’s Texas squad, Kevin Costner was a great player who just couldn’t quite reach the heights of Garrido’s Fullerton team. Instead, Costner took up acting and filmmaking. By the time of his retirement in 2016, Garrido had led the Horns to another 8 conference championships and 2 national titles.

Kevin Costner’s film “For Love of the Game,” is about an aging pitcher who throws a perfect game in his last major league start. Costner’s character is a Detroit Tiger, the same team against which Roo Charlie Robertson was perfect in 1922. In Costner’s movie, Vin Scully has the call. Scully also called Dob Larsen’s perfect game in 1956. The perfect game in Costner’s movie takes place at Yankee Stadium, the same place as Larsen’s perfect game. Larsen’s perfecto was the first in 34 years since Charlie Robertson’s 1922 gem.

And who is cast as the Yankee Manager in “For Love of the Game?” Why, it’s Longhorn Augie Garrido, the Cal State Fullerton manager who had cut Costner from his squad decades earlier. Garrido and Costner became close friends over the years that followed.

In “For Love of the Game,” Garrido sends in a pinch hitter with two outs in the ninth in order to “wreck” the perfecto of Costner’s character. In 1922, Detroit Tigers player-manager Ty Cobb also sent in a pinch hitter with two outs in the ninth in order to “wreck” the perfecto of Charlie Robertson. Garrido fails in the movie, and Cobb failed in real life. Both stories have happy endings. Clips from Costner’s movie will be used to tell the story of Charlie Robertson and his perfect game in 1922.

The 2019 season for UT Longhorn baseball kicks off today; the alumni game is taking place at Disch-Falk field. At Disch-Falk, three statues have now become four. Billy Disch, Bibb Falk, and Clif Gustafson now have company. The statue of Augie Garrido, who passed away in 2018, was dedicated today alongside his three predecessors during the UT Alumni Game. Roger Clemens pitched one inning with his sons playing defense. Fans waited for autographs. David Pierce, the fifth UT baseball skipper since 1911, began a campaign to return to the College World Series.

Kevin Craig, the Longhorn version of Kevin Costner, has been tremendous help for this Roo Tale. He will likely come around again in future previews. Kevin, Hook ‘em Horns. Let’s try to pull off UTD against the Roos at AC. I’ll show you exactly where the great Charlie Robertson pitched in Sherman, before his incredible perfect game against Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers.

Longhorn Baseball, good luck in 2019. More Saturday Charlie Robertson previews to come.

Roos who like the Texas Longhorns: Kaitlin Elledge, Jacob Morgan, Wayne Whitmire, Laura Elizabeth, Jeff Duffey, James Hartless, Monica Walters Crowley, Shannon Harpold Hutcheson, Ed Garza, Celeste Lunceford Havis, Ruth Nuckols Cox Williamson, Stephen Sides, Betsy Walling Furler, Walker Fenci, Trisse Edwards Brown, Lin Waters, Angeleena Young, Darren McDowell, Judson Crowder, Melissa Swedoski, Shelley Odom, Tom Boyd, Cooper Woodyard, Scott Slaughter, Gerald Brown, Michael Clark, Jennifer Wroten Clarke, Joe Devine, John Cotton, AJ Graham, Jason Willis, Bill Garza, Tate Gorman, Tom Thompson, Drew Whatley, Tyler Tarbox, Palmer Johnson, Vanessa Johnson, Kirk Patrick Lipsitz, Kelly Grekstas

Tyson J. Spring Aron Waisman

Charlie Robertson’s perfect game against the Detroit Tigers in April 1922 may just be the most amazing accomplishment in Austin College sports history.

But maybe, just maybe, we can go even further.

Pitching performances range from the common (a win) to the rare (a no-hitter). Are no-hitters really that rare though? There have been 256 since 1901, roughly one every six months. They happen pretty much every year; the last season with zero no-hitters was way back in 2005. Nolan Ryan had a record 7 no-hitters over his career, but he allowed an average of four walks over those 7 games. All things equal, it’s easier to keep the hits to a minimum when you can waste a few at-bats by avoiding the strike zone.

But imagine both throwing strikes and avoiding hits. That, combined with stellar defense, is a perfect game. It’s really rare. Since 1901, it’s only happened 21 times. That’s once every six years. We’ve had more Presidents since 1901 than perfect games.

Robertson threw his perfecto when Warren Harding was President. By the time Don Larsen pitched the next one in the 1956 World Series, the United States had been through the Roaring Twenties, a Great Depression, and a World War. Dwight Eisenhower was barely removed from his football career at Army in 1922. By 1956 he had liberated Europe and was running for re-election.

21 perfect games, and an Austin College Kangaroo threw one of them. Outstanding. But maybe, just maybe, we can go even further.

Of the 21, which is the most impressive? You can make a strong case that the most perfect of perfect games was thrown by Charlie Robertson. Let’s go through the evidence, category by category.

PITCH COUNT:

The most dominating perfect games have low pitch counts. These hurlers are hitting the strike zone, recording few balls, and avoiding foul balls from contact. In his 1922 perfect game, Robertson tossed 90 pitches.

The average number of pitches in a perfect game is 103. A majority have exceeded 100; even Randy Johnson’s dominating 2004 perfect game was completed after 117 pitches. Only two perfect games have seen fewer: Addie Joss (Cleveland) in 1908 and David Cone (New York) in 1999. Cone’s 88 pitches at Yankee Stadium was thrown in the presence of Don Larsen, who was honored that day for his 1956 gem.

HOME/AWAY:

If you think more perfect games are thrown at home, you’re right. 13 (62%) have occurred within the friendly confines of a hometown ballpark. 8 pitchers, including Roo Charlie Robertson, had to overcome a hostile home crowd and unfamiliar park to finish their perfect outings. Interestingly however, is to note the reaction of baseball fans to a visiting pitcher perfecto. They turn.

According to James Buckley Jr., author of “Perfect: The Inside Story of Baseball’s Perfect Games,” a home town crowd always turns in inning 8. Never inning 7. Never inning 9. Inning 8. This is true for Robertson as well. After Robertson’s strike out of Ty Cobb to end of the 7th, every Detroit Tiger fan began rooting for the Roo to finish the job. Ty Cobb was not happy with this turn of events, but unfortunately for Cobb Detroit Tigers fans are also baseball fans.

WEATHER:

Have you ever seen a pitcher in a dugout wearing a coat over his pitching arm? Pitchers need warmth to be effective. You won’t be surprised to learn that most perfect games have occurred in the summer.

10 perfect games have occurred in the summer months of June to September. Another 9 have taken place in the more moderate months of May & October. Only two perfect games have been tossed in the near winter month of April: Charlie Robertson (1922) and Philip Humber (2012). Ironically, both Robertson and Humber are Texans who threw their perfectos for the Chicago White Sox. Humber is a native of Carthage, TX, home of Roos Otis Amy, Chris Medlin, Billy Kuykendall, and many others.

What was the weather in Detroit, MI at noon on April 30, 1922? Upper 40s and sunny. Definitely not ideal perfect game weather. But a perfect game was thrown nevertheless.

EXPERIENCE:

Seven pitchers with perfect game honors sit in Cooperstown: Randy Johnson, Sandy Koufax, Catfish Hunter, Roy Halladay, Jim Bunning, Addie Joss, and Cy Young all had hall of fame careers. David Cone and Felix Hernandez both won Cy Young Awards and were elected to multiple All-Star games. Dennis Martinez, Kenny Rogers, David Wells, and Mark Buehrle each won 200 games. Matt Cain, Mike Witt, and Tom Browning had long careers with over 100 career wins.

Only five perfect games have been thrown by pitchers with journeyman careers. Don Larsen, Len Barker, Dallas Braden, Philip Humber, and Charlie Robertson. Of the five, Robertson had by far the least Major League experience. The average years of experience for the 20 pitchers excluding Robertson is 8. Robertson’s perfect game was only the THIRD start of his professional career; he is the only rookie to have ever thrown a perfect game.

BALLS TO THE OUTFIELD:

The most dominant perfect game pitcher is going to keep the batter jammed, frustrated, and not getting good wood. That means infield grounders and foul pop ups. Shots to the outfield mean that batters are connecting.

Charlie Robertson allowed just 6 balls to the outfield. Only six other perfect game hurlers allowed fewer. Tom Browning, Kenny Rogers, David Cone, and Dallas Braden each allowed 9. Don Larsen saw 10. Robertson’s effort in this category, like every other category, places him in the top half once again.

OPPOSITION:

Not convinced yet? Well, you can take all of the arguments so far and discard them. They all pale in comparison to this last one. The opposition. Of the opposing teams which endured a perfect game, which had the most offensive prowess? Hands down, it’s the 1922 Detroit Tigers.

On Base Percentage (OBP) measures how often a batter reaches base (hits, walks, hit-by-pitch, sacrifice). The average OBP of the 20 teams faced by perfect pitchers other than Robertson? 0.316. That’s pretty typical. The OBP average of the entire Major Leagues in 2018 was roughly the same at 0.318.

The OBP of the 1922 Detroit Tigers? An incredible 0.373. That’s nearly 20% higher than the average of all other opponents.

Batting Average (BA) measures hits alone, is usually about 60 points lower than OBP, and was a more commonly used statistic 100 years ago. The Detroit Tigers had a team batting average of 0.316 in 1921. It remains the highest team batting average in the modern era since 1901.

I’m going to repeat myself. I don’t quite think you heard me. Read slowly.

In 118 years (~2000 team seasons) of major league baseball, no team has ever had a batting average higher than the 0.316 average of the Detroit Tigers in 1921. Heck, most ballplayers who hit 0.316 are having a career season. Hall of Famer Joe DiMaggio had a lifetime average just a tad higher than 0.316. The 1927 New York Yankees, considered by some to be the best team in history, had a team BA of .307. That’s nine points lower than the 1921 Tigers if you’re scoring at home.

The 1921 Detroit Tigers were simply a MONSTER hitting club, with historically unprecedented firepower right down the line. Not just the great Ty Cobb. Names like Veach. Heilmann. Cutshaw. Blue. Rigney. A true Murderer’s Row. The entire lineup was back in 1922, and almost matched the prior year’s record by hitting a 1927 Yankees-like 0.306.

You may wonder why Ty Cobb’s Detroit Tigers never won a World Series in the 1920s. The answer is simple. Poor pitching. Detroit desperately needed more Charlie Robertsons. There will be a Charlie Robertson Saturday preview to come specifically devoted to the offensive prowess of the 1922 Detroit Tigers.

Robertson’s effort may not only have been the best perfect game, from a literary perspective it was the first:

From Buckley Jr.:

“In all these articles, writers continued to struggle for a definition of the deed. One 1911 article in the Toledo Blade includes the tortured phrase: a “no-run game, no-hit game, no-man-reaching-first game.” In 1922, in response to Charlie Robertson’s stunning performance against the Tigers, a writer named Ernest J. Lanigan finally saved us all from the extended use of hyphens by first using the term “perfect game.”

Oh yeah, and remember those 256 no-hitters since 1901 mentioned earlier? The opposition BA of every one of those 256 teams was lower than the BA of the Detroit Tigers faced by Charlie Robertson. According to Buckley Jr., this statistic combined with all of the others lead sports author and historian “John Thorn to call Robertson’s feat ‘perhaps the most perfect game ever pitched.’” Today, Thorn is the official baseball historian for Major League Baseball.

Just imagine.

It’s April 30, 1922. It’s a chilly day. You’re been picked to start for only the third time in a rookie season of a major league career. You are on the road in a hostile environment. You are facing the best hitting team in the history of the game. The star of that team is Ty Cobb, the best hitter in baseball history with a lifetime average of .367. You are far, far from the collegiate contests at Luckett Field in Sherman, TX.

And what do you do? You pitch a perfect game. Only the third since 1901, and only 18 since.

It’s crazy to say, right? So I’m not going to say it. Nope, it’s ridiculous. I can’t say it. It’s silly. Then again, maybe it’s not so silly. Maybe it’s just where the facts lead. Maybe it’s clear, and just insufficiently recognized. Maybe it’s obvious. It is obvious. So I’m gonna go ahead and say it.

The perfect game by Kangaroo Charlie Robertson on April 30, 1922 against the Detroit Tigers is the best pitching performance in the history of baseball.

Yeah, I said it.

If it’s a baseball Roo Tale, then you better believe Imma gonna tag circa 1990 Roo baseball:

David Norman, Pat Rabjohn, Jason Willis, Shane Montgomery, Jimmy Baird, Phil Novicki, Ryan Nicholson, Pat Abernathey, Jamie Muro, Wayne Whitmire, Kelly Carver, B.k. May, Bj Wastoskie, Wes Tarbox, Kyle Matlock

More Saturday previews to come.

Look. At. That. Chart. See the comments.

It’s a chart which compares the On Base Percentage (OBP) of all teams which had to endure a perfect game. OBP measures how often a batter reaches base (hits, walks, hit-by-pitch, sacrifice). The average OBP of the 20 teams faced by perfect pitchers other than Austin College Kangaroo Charlie Robertson? 0.316. That’s pretty typical. The OBP average of the entire Major Leagues in 2018 was roughly the same at 0.318.

The OBP of the 1922 Detroit Tigers, against whom Robertson was perfect? An incredible 0.373. That’s nearly 20% higher than the average of all other opponents. Robertson pitched his perfect game against the Tigers on April 30, 1922 in Detroit.

Batting Average (BA) only measures hits, is usually about 60 points lower than OBP, and was a more commonly used statistic 100 years ago. A BA of 0.250 is considered average; in fact, the BA of the entire Major Leagues in 2018 was not far off at 0.248.

The 1921 Detroit Tigers had a team batting average of 0.316 in 1921. It remains the highest team batting average in the modern era since 1901. In 118 years (~2000 team seasons) of major league baseball, no team has ever had a batting average higher than the 0.321 average of the Detroit Tigers in 1921. The Tigers came close to matching their output in 1922 by hitting 0.306, just a point lower than the 1927 New York Yankees.

The 1927 Yankees with its famed Murderer’s Row is considered by some as the best hitting team in the history of the game. That’s not the case. The truth is that the 1927 Yankees were a team with great pitching and great hitting. The 1922 Tigers? Poor pitching and EXTRAORDINARY hitting. No team could hit like the Detroit Tigers, which makes Charlie Robertson’s perfect game on April 30, 1922 that much more remarkable.

Who are they 1922 Detroit Tigers? This preview will go through the amazing lineup, batter by batter. With almost no weak spots in the order, Robertson would have been lucky to pick up a win that day. How the Roo was perfect remains something only the baseball gods can explain. As official MLB historian John Thorn put it, Robertson’s feat is “perhaps the most perfect game ever pitched.” Let’s meet Robertson’s victims, the starting lineup of the Detroit Tigers on April 30, 1922:

Batting in the leadoff position: First baseman Lu Blue

Luzerne Atwell “Lu” Blue enjoyed a 13-year major league career. He was a switch-hitter with a career on base percentage (OBP) of .402. His best season was his 1921 rookie year in Detroit, when the Tigers set the MLB team BA record that still stands. Aided by a strong ability to draw walks, Blue’s OBP in 1921 was an impressive 0.416. Blue was among the league leaders in walks ten times during his career. He credited Ty Cobb with helping him to improve his hitting in the majors.

Batting second: Second baseman George Cutshaw

Cutshaw’s 12-year major league career was near its end in 1922. He hit 0.267 that year with a respectable 0.300 OBP, not far off of his career averages. Cutshaw would have been a welcome addition to any major league lineup. Compared to his 1922 Detroit Tiger teammates, however, he was below average.

Batting third: Center Fielder Ty Cobb

Ty Cobb is the best hitter in the history of baseball. His 0.367 career batting average is first all time, and his career 0.433 OBP places Cobb in the top ten all time. In 1922, Cobb was at the peak of his game. He hit 0.401 that year, one of only 7 players to top the .400 barrier. His league leading 0.401 average in 1922 was topped by Cobb’s Tiger teammate Harry Heilmann and his 0.403 average in 1923. Cobb was one of the “original six” of the first Hall of Fame class in 1936. His 4,191 hit total was an iconic baseball record until finally broken by Pete Rose in 1984.

Batting Cleanup: Left Fielder Bobby Veach

Nobody in baseball had more RBIs or extra base hits between 1915 and 1922 than Bobby Veach. The 14-year veteran of the majors hit for both power and average; he finished second to Ty Cobb for the AL batting title in 1919. His 1922 BA of 0.327 was one of his best seasons. The Detroit outfield of Veach, Cobb, and Heilmann are considered by some historians as the best hitting outfield in baseball history.

Batting fifth: Right Fielder Harry Heilmann

Heilmann was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1952. He hit a remarkable 0.342 over 17 major league seasons. In 1923, one year after Robertson’s perfect game, Heilmann stole the batting title from Cobb after hitting 0.403. His OBP that same season was an impressive .481; in other words, Harry Heilmann safely reached first base in almost 1 of every 2 at-bats. His lifetime OBP of 0.409 places him at #36 on the all-time list, just ahead of Jackie Robinson.

Batting sixth: Third baseman Bob Jones

With a career BA of 0.265, Jones was one of the less productive hitters in the Detroit lineup. Over 9 years in Detroit, Jones compiled a career OBP of 0.314 with 791 hits, 208 walks, and 310 RBIs. Jones hit 0.300 one time in his career, the record setting year of 1921. Still, Jones would have found a spot on any other team lineup. His career BA was still nearly 20 points higher than the league average in 2018.

Batting seventh: Shortstop Topper Rigney

As a rookie in 1922, Rigney hit 0.300 and recorded an OBP of 0.380. 1922 and 1923 were his most productive years over a six-year major league career. Rigney grew up in Leonard, TX near the Grayson County border. A contemporary of Robertson, he played for Texas A&M from 1915 to 1918. Rigney was plagued by injuries after the 1923 season, which forced an early retirement.

Batting eighth: Catcher Clyde Mannion

Mannion’s career BA of 0.218 was one of the lowest on the Tiger team; he was the only member of the starting lineup to hit below the 2018 major league average. However, Mannion had won of his best seasons in 1922, hitting 0.275 with an OBP of 0.315. He ended his 13 years in the majors in 1934 with a career OBP of 0.293, respectable among defensive minded catchers of the era. Even Detroit’s catcher could hit.

Batting ninth: Pitcher Herman Pillette

Not surprisingly given his pitching role, Pillette was by far the weakest member of the lineup on April 30, 1922. Pillette hit a poor 0.172 in 1922 with an OBP of only 0.204. However, he only batted twice against Robertson. With Pillette on deck with two outs in the ninth, Ty Cobb replaced his starting pitcher with a pinch hitter in a desperate attempt to wreck Robertson’s perfect game. That pinch hitter was backup catcher Johnny Bassler.

Pinch hitter: Catcher Johnny Bassler

According to the “Detroit Athletic,” Bassler “excelled at one thing almost better than any other hitter in history – making contact. Four times Bassler hit over .300, batting 0.346 in 1924. His penchant for striking the ball came at a cost – he rarely hit for power. But Bassler was a master at getting on the bases. He posted an OBP over 0.400 in every season he played for Detroit. In 1924 his 0.441 OBP was second only Babe Ruth.”

Player Manager Ty Cobb was furious. The Detroit Tigers would often lose a ballgame because of pitching, but they were never shutdown offensively. Yet here was a rookie pitcher fresh out of Austin College completely owning the greatest hitting team in history and shutting down himself, the greatest batter the game had ever known. After 26 outs and no base runner to show for it, Cobb desperately inserted Bassler as a pinch hitter with orders to “wreck” Robertson’s perfect outing. Like the mighty Tigers that came before him, Bassler failed. Cobb left Tiger Stadium in disgust as Robertson celebrated out #27 alongside his Chicago White Sox teammates.

The Detroit Tigers finished the 1922 season just four games above 0.500, in third place in the AL won by the New York Yankees. Their pitching was primarily to blame. Chicago only managed 2 runs on April 30, 1922; that low total usually would have been enough for a win for a Detroit team that averaged nearly 6 runs a game. But neither runs, nor hits, nor walks, nor errors would be on the scoreboard by the end of the day.

Since 1901, there have been roughly half-a-million pitching starts in the Majors. Only 21 of those ~500,000 starts have resulted in a perfect game. The odds of witnessing a perfect game at any random baseball game is 0.00008%. The odds of being struck by lightning? 0.0003%. You are four times more likely to get struck by lightning.

The odds of pitching a perfect game against the 1922 Detroit Tigers? That’s like being struck by lightning while the lightning is itself struck by lightning.

More Saturday previews to come. To read previous Charlie Robertson previews or to be notified of future previews and the story itself, join the Go Roos FB group in the comments.

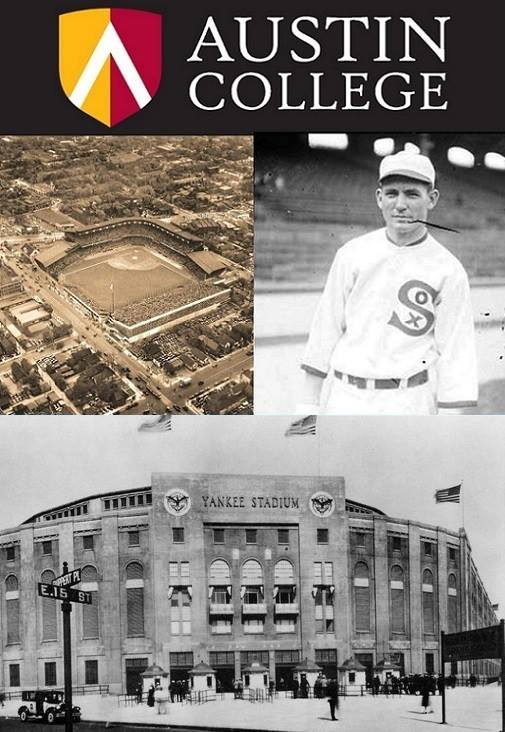

The old Polo Grounds had been grudgingly used for decades. In 1923, however, the New York Yankees finally had a ballpark of their own. Yankee Stadium. Over the past century, the House that Ruth Built has seen its fair share of Roos.

The iconic home to the Yankees opened in the Bronx to great fanfare on April 18th. Babe Ruth would lead the 1923 Yankees to a World Series title, their first of now 27 championships. New York won the first ever game at Yankee Stadium by defeating the Boston Red Sox.

The stadium had already seen 37 contests when the Chicago White Sox arrived for a four game series on July 28th. Waite Hoyt, a member of the 1927 Yankees who sits in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, got the start for New York. On the mound for Chicago was Austin College Kangaroo Charlie Robertson, one year removed from his perfect game at Detroit in 1922. The White Sox took a lead in the 5th, and held on for a 3-1 win. Robertson had a strong outing, scattering 8 hits over 9 innings and earning the complete game win. The Roo even helped his own cause with two singles and a sacrifice. The lone Yankee run was scored by Babe Ruth.

The 1927 Yankees are often considered the best team in league history, and an Austin College Kangaroo was a valued contributor. Ray Morehart, Class of 1922, was a utility infielder for the team of Ruth & Gehrig. For 2 months during the summer of 1927, he was a starting second baseman and member of the famed murderer’s row. On June 8th, 1927, Morehart was the toast of the town. The Yankees found themselves down 11-6 at home to the second place White Sox in the bottom of the ninth. A dramatic comeback fueled by Ruth, Lou Gehrig, & Tony Lazzeri tied the game at 11 and sent it into extra innings. In the bottom of the 11th, Yankee Cedric Durst led off with a triple and Lazzeri was intentionally walked. With darkness approaching and Yankee fans on their feet, Ray Morehart walked up to the batter’s box.

Morehart slapped a single to right on the first pitch, and Durst walked home with the winning run. Yankee fans exploded as Ruth, Gehrig, and teammates rushed towards first to celebrate with the Roo. Morehart finished the game with a run, a stolen base, and two hits……including the game winning RBI walk off. “A winning single from the bat of little Ray Morehart pierced the gathering darkness in Yankee Stadium along about supper-time Wednesday and broke the spell of the season’s most exciting ball game,” screamed the Decatur Herald.

Kangaroo Tom McBride helped Ted Williams get to his only World Series in 1946 as a member of the Boston Red Sox. On September 2, 1946, McBride got the start in right field at Yankee Stadium. In the 3rd, McBride singled to center scoring a run. He advanced to third, and a balk to Ted Williams brought McBride home. The former Roo outfielder went 2 for 3, and the Red Sox won 3-1. Boston clinched the AL pennant 11 days later.

The Yankees were back in 1956. They clinched the AL pennant and met the Brooklyn Dodgers in the World Series. In Game #5, journeyman pitcher Don Larsen took the mound at Yankee Stadium. It had been 34 years since Charlie Robertson’s perfect game, and many were wondering whether it would ever happen again. On October 8, 1956, lightning finally struck again, and on baseball’s greatest stage. Larsen was perfect, and catcher Yogi Berra famously jumped into Larsen’s arms after the final strikeout. A young Vin Scully was behind the mic with the call.

Charlie Robertson, a long forgotten figure who was now a farmer & businessman in Fort Worth, was all of a sudden a hot commodity. Where was he, and what did he think about Larsen’s effort? The press soon learned that Robertson was not terribly interested, and had left the game behind. Baseball had not been too kind to him after his perfecto. In a 2015 interview with Bob Costas alongside Yogi Berra, Don Larsen mentioned Robertson while revisiting his perfect game in 1956.

Gene Babb and the San Francisco 49ers traveled to Yankee Stadium to face the New York Giants in December of 1957. Babb scored on an 8 yard run to give San Francisco an early 7-0 lead. A late Frank Gifford TD pass made it close, but the 49ers held on for a 27-17 win. The Kangaroo finished with 70 all-purpose yards.

Babb and the 49ers ended a disappointing 1958 with a win at home over John Unitas and the Division Champion Baltimore Colts. The next game for the Colts was the NFL Championship at Yankee Stadium. Baltimore’s victory over New York in overtime is considered by some as the “Greatest Game Ever Played” and the birth of the modern NFL. Babb returned to Yankee Stadium a final time in 1960 as a member of the league’s newest franchise, the Dallas Cowboys.

Yankee Stadium was the site of the college football’s Gotham Bowl in 1962. Bob Devaney’s Nebraska Cornhuskers faced the Miami Hurricanes on December 15th in 10-degree weather. Led by future Austin College Kangaroo Coach Larry Kramer on the offensive line, Nebraska scored three rushing touchdowns and defeated Miami 36-34.

Former Austin College Coach Joe Spencer was an OL coach with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1971. The Cardinals traveled to Yankee Stadium in late November to meet the New York Giants. St. Louis frustrated Giants QB Frank Tarkenton most of the day. Spencer and the Cardinals returned to St. Louis with a 24-7 victory.

Don Mattingly was New York’s MVP during the lean Yankee years of the 1980s. On July 8th, 1987, Mattingly homered at Yankee Stadium; he repeated the feat over the next four games in the Bronx, as the Yankees left the Bronx for a three game series in Texas against the Rangers. Mattingly hit a home run in each of the three games in Arlington, extending his streak to an MLB record 8 games previously held by Yankee Lou Gehrig. In the stands for home run #8 on July 18th was Austin College Kangaroo and former Yankee Ray Morehart, who was interviewed by the Dallas Morning News about Mattingly and Gehrig.

Yankee Stadium has even hosted Roos who write Roo Tales. I was in New York in 1999, and headed to the Stadium with Sridhar Yaratha and Frank Tooley on July 3rd. New York was down 5-3 headed into the bottom of the ninth, but Scott Brosius belted a three run walk off homerun to win the game in front of an ecstatic Yankees crowd. 15 days later, the Expos were in town and David Cone was in the mound. It was Yogi Berra day.

Don Larsen was there to throw out the first pitch to Berra, and stayed to watch the game. Incredibly, Larsen saw Cone throw a perfect game against Montreal, the third ever at Yankee Stadium and the 11th since Charlie Robertson. Scott Brosius, who we had seen slap the walk off earlier in the month, caught the last out.

1999 was also the year “For Love of the Game” was filmed at Yankee Stadium. The movie, based upon the book by Michael Shaara, tells the story of a pitcher who throws a perfect game against the Yankees on the last weekend of the season at Yankee Stadium. Vin Scully stars in the movie, and Don Larsen is mentioned. 1999 was a year of perfect games at the House that Ruth built, both real and imagined. The movie “For Love of the Game” will be used to tell the story of Charlie Robertson’s perfect game in 1922.

The old Yankee Stadium is no more. A more modern version was built in 2009 right next door, and the stadium where Charlie Robertson won in 1923 has been torn down. But like Tiger stadium in Detroit, the diamond remains. The ballpark lives on as Heritage Field, a public park in the Bronx. You can still visit the site that Roos have graced for nearly a century, ever since Charlie Robertson walked to the mound in year #1 of the iconic stadium and defeated Ruth and the Yankees in 1923.

More Charlie Robertson Saturday previews to come.

A perfect game is nearly impossible to achieve. A hurler has to throw strikes and avoid hits for 27 batters. Yet even that is not enough. No perfect game is complete without a third ingredient. Great defense.

The movie “For Love of the Game” will be used to tell the story of Charlie Robertson, the Austin College Kangaroo who threw a perfect game against the Detroit Tigers in 1922. In the movie, Tigers pitcher Billy Chapel has thrown 7 innings of perfect ball. But he’s done, he’s finished. He can’t get the final six batters. Chapel tells his catcher Gus that he doesn’t think he has “anything left.” Gus responds:

“You just throw whatever you got, whatever’s left. The boys are all here for ya. We’ll back ya up. We’ll be there. ‘Cause, Billy. We don’t stink right now. We’re the best team in baseball right now, right this minute, because of you. You’re the reason. We’re not gonna screw that up. We’re gonna be awesome for you right now. Just throw.”

Yup. In the movies, everything follows a script. The very next Yankee batter launches a shot to right, but the Tiger right fielder leaps over the wall and brings the ball back into the park with the glove. Chapel’s perfecto is still alive.

There have been a handful of incredible defensive gems among the 21 perfect games thrown in the modern era. Most of these plays have occurred late, when the pitcher was on the ropes and needed the assistance. In the end, a perfect game is a team effort. It’s a play, with the pitcher as lead, the catcher as supporting actor, and an entire crew of valuable extras.

San Francisco Giants pitcher Matt Cain threw perfect game #20 in 2012 against the Houston Astros. He had retired 18 batters entering the 7th inning, but Astro #19 launched a shot in the gap to right. Right fielder Gregor Blanco sprinted like Carl Lewis, tracked it down, dove on the warning track, and came up with the perfecto saving catch. Matt Cain tipped his cap to Blanco, and got the next 8 batters.

Texas Rangers pitcher Kenny Rogers threw his perfect game in 1994 at the Ballpark at Arlington, the 12th since 1901. Rogers was perfect after 24 batters heading into the ninth, but a drive to shallow center led Rogers to believe his effort was finished. Rusty Greer thought otherwise. The Rangers center fielder raced towards first, dove, and amazingly came up with the ball. The Rangers radio broadcast, knowing that the 1994 baseball strike was looming, remarked “thank god they didn’t set the strike date for July 27th.“ Rogers got the last two batters; his perfect game is the only one ever thrown in the state of Texas.

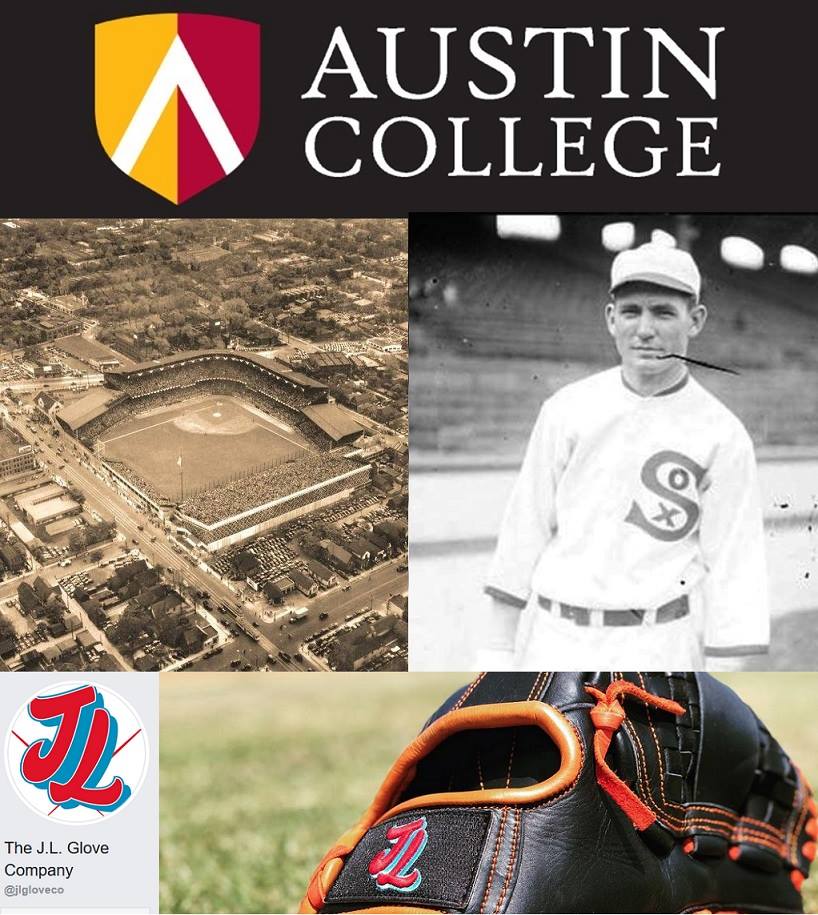

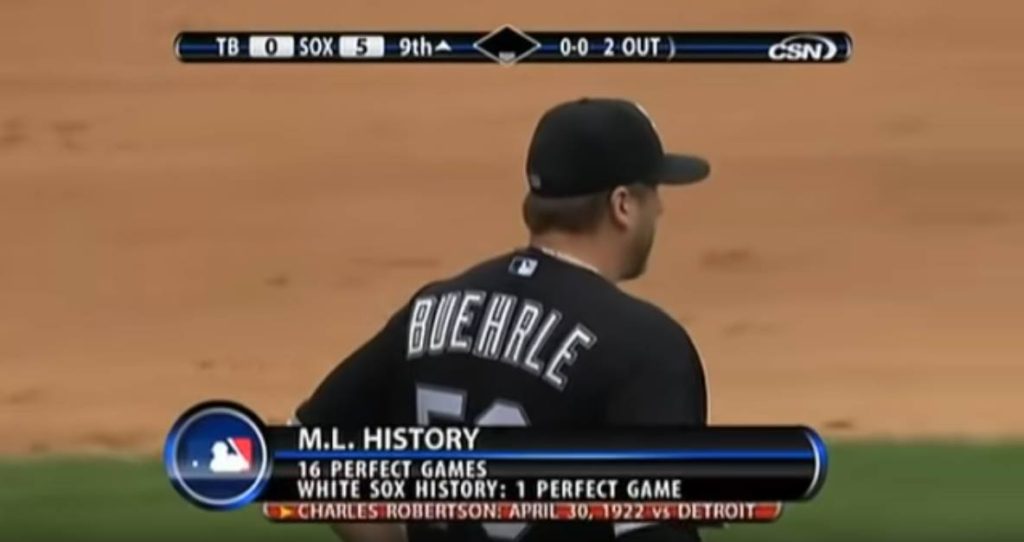

But the best defensive play of all time in a perfect may have just come, ironically, from the Chicago White Sox. In 2009, Mark Buehrle had a perfect game going at Comiskey as the ninth inning began. No White Sox pitcher had ever thrown a perfect game since April 30, 1922, when Austin College’s Charlie Robertson baffled Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers. Buehrle was running on fumes with three outs to go when Tampa Bay batter #25 launched a shot to center. Center fielder DeWayne Wise had just been inserted into the game and was playing shallow. It didn’t matter. Wise sprinted like the perfect game depended upon it, leaped over the wall, and miraculously brought it back in play with the glove. The collision with the wall jostled the ball from the glove; while falling to the ground, Wise secured the ball with his throwing hand.

It was arguably the best defensive play ever to preserve a perfect game. Buehrle struck out batter #28, and the name “Charlie Robertson” flashed on the television screen with one out to go. A grounder to short clinched the first White Sox perfecto in 87 years. Roo Charlie Robertson no longer stood alone within the White Sox organization. Wise’s defensive gem has been immortalized at Comiskey; the site of the wall where he saved Buehrle’s perfect game is today labeled “The Catch.”

Good story telling requires great assistance, just like good defense requires great gloves. I’m thankful for a lot of guys in the Austin area who are helping with this story: Kevin Craig, Aron Waisman, and especially Tyson J. Spring. Tyson’s business venture, The J.L. Glove Company, offers “fine baseball gloves made by hand.” The company’s motto is: “27 outs. Go get one.” They’re a great gift for any serious, veteran ball player in your family or within your circle of athlete friends.

There’s no money in writing a Roo Tale, nor is their money in assisting with one. Those who have helped before have done so only “For Love of the Game”; the same is true for Tyson. If you enjoy these Roo stories and want to support, then consider either purchasing a glove from J.L. Glove, telling your friends and family about the company, or simply sharing or liking the J.L. Glove Facebook page for your community. See the comments for links to the webpage and FB page.

Charlie Robertson was dominant in 1922 against the Detroit Tigers, but even he needed assistance from his outfield on the warning track. He got it, and secured one of only 21 perfect games in MLB history. That story to still to come as we approach Opening Day.

Thanks guys for your willingness to help with this story. Everybody, go support J.L. Glove. There are 27 outs in a perfect game. Go get one.

More Saturday Charlie Robertson previews to come.

I’ve got two questions for all of you baseball folks out there in Facebook land.

I’ve posted a picture from a baseball game. You can see the pitcher with his delivery. The batter checks his swing and does not go around. If you look closely, you can see the streak of the baseball just in front of the catcher.

The footage is old. The angle is not ideal. It’s a tough question to answer. But give it a shot.

Here’s question #1:

Is this pitch a ball or a strike?

Now, what if I told you that the pitcher was Milt Pappas on September 2, 1972? And that Pappas had a perfect game with two outs in the ninth? And that this pitch was his 3-2 offering to batter #27? And that the call by umpire Bruce Froemming is the difference between a perfect game and baseball history (a strike) or just another win at Wrigley (a ball)?

Take a closer look with all of that in mind. It’s a tough question to answer. But give it a shot.

Here’s question #2:

Is this pitch a ball or a strike?

This story is a part of yet another Saturday preview stiof Austin College Kangaroo Charlie Robertson, who pitched a perfect game in 1922 against Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers. Still to come.

Robertson, unlike Pappas, did get batter #27 to complete his perfecto. Pappas and Froemming would feud for a quarter century over the pitch you are looking at right now.

Here’s a stat I think is kinda neat. In the year 1924, three Austin College Kangaroos sat in the dugout of Comiskey Park as members of the Chicago White Sox: Charlie Robertson, Ray Morehart, and Wally Dashiell. Back in 1986, the press referred to the Boston Red Sox as the “Austin” Red Sox because of the presence of Roger Clemens, Calvin Schraldi, and Spike Owen. Maybe we should rename that 1924 White Sox team after Sherman.

Comiskey Park was the brainchild of owner Charles Comiskey, who dreamed of a stadium like no other. At its completion in 1910, it was one of the largest and most modern in the world. The park seated 32,000, a record at the time. It’s nickname? “Baseball Palace of the World.”

Comiskey’s tenure saw the 1917 White Sox win a World Series title. The bulk of that championship team was back in 1919, but famously threw the World Series to combat the greed and injustice of their legendary owner. Austin College Kangaroo Charlie Robertson was briefly a member of the 1919 Sox, before being sent down to the minors. The White Sox would suffer for 88 years before finally winning another World Series title.

Robertson was back in Chicago in 1922, and made baseball history with a perfect game in his second start. He spent three more seasons with the White Sox, before being traded to St. Louis and Boston and retiring in 1929. Robertson was joined in 1924 by AC’s Ray Morehart, who would go on to play a contributing role on perhaps the best team in history, the 1927 New York Yankees. And for one brief, shining month, Robertson and Morehart were joined by a third Kangaroo at Comiskey. Wally Dashiell.

In April of 1924, Roo Wally Dashiell was called up to the majors. He sat for most of the month alongside his Roo alumni, and finally got to play on April 24th.

Dashiell was inserted at shortstop halfway through a home game against Cleveland. His first two plate appearances were both strikeouts. The White Sox 8th inning began with the Cleveland Indians up 4-1. But a rally was about to get underway at Comiskey, and Dashiell would be a part of it.

Chicago closed the gap to 4-3, and had men on 1stand 2nd. Dashiell was called to sacrifice, and he delivered. The runners advanced, and would later score on a hit and squeeze play. Chicago won 5-4, and Dashiell was a contributor. As he left Comiskey that afternoon, his fellow Roo teammates Robertson and Morehart probably slapped him on the back and muttered “fine job.”

Dashiell would never play in the majors again. His career major league statistics: 3 plate appearances, 2 at-bats, 1 sacrifice, 0 hits/walks. One game. Like the Burt Lancaster character in the movie “Field of Dreams,”, he was Austin College’s Moonlight Graham.

Comiskey was also the site of some early games in the newly created National Football League. The Cardinals of Chicago called Comiskey home from 1922 to 1958, before relocating to St. Louis and now Arizona. Cecil Grigg and his Canton Bulldogs defeated the Cardinals at Comiskey in 1922, on their way to an undefeated NFL title in the third year of the league. Kangaroo Joe Carter, a wide receiver (end) at AC in the early 1930s, enjoyed a 13 year NFL career with 4 teams. Carter had nearly 2,000 yards in career receptions and scored 22 TDs. He ended his career at Comiskey with the Chicago Cardinals in 1945. Tackle Joe Coomer, an AC graduate from the late 1930s, helped guide the Cardinals to an NFL title in 1947. The Cardinals finished 1st in the West Division, and defeated the Philadelphia Eagles in the NFL title game at Comiskey. Coomer finished his NFL career in Chicago two years later.

After 42 long years, the White Sox finally returned to the World Series in 1959. Chicago lost that series to L.A. in six games; the Dodgers clinched game #6 at Comiskey. The series featured the largest crowd to ever see a major league baseball game. Having just relocated from Brooklyn one year earlier, L.A. played their home games at the Memorial Coliseum. Nearly 93,000 came to watch Sandy Koufax, an old basketball teammate of Coach Sig Lawson, lose Game #5 to Chicago. Chicago would not return to the World Series for another 46 years.

Disco music died at Comiskey. As part of a Bill Veeck promotion in 1979, a local radio DJ declared Disco Demolition Night at the ballpark. Every fan who brought a Bee Gees album to donate to the explosion would be allowed entry for a dollar. White Sox ownership expected a few hundred extra to show. Instead, half the city of Chicago climbed into the stadium. The explosion took place in the outfield during the middle of a double header that would never occur. After the blast, White Sox fans raced onto the field by the thousands, and the second game had to be forfeited by Chicago. The Bee Gees swear that their record sales immediately dropped after the incident.

Are you a fan of the iconic song “Na na na na, na na na na, hey hey hey, goodbye” sung nationwide at sporting events? That’s a Comiskey creation. White Sox organist Nancy Faust began playing the obscure tune when opposing pitchers would exit, and it caught on like a wildfire. The became a Comiskey staple, even featuring in a White Sox comercial. Today, it’s pretty much a standard at your typical American sporting event.

By 1990, it was time to say goodbye to old Comiskey. The demolition of the historic park caused a great deal of angst in Chicago and around the nation, so much so that an effort began to preserve old ballparks (Wrigley & Fenway) and build new ones in their image (Camden Yards & the Ballpark at Arlington). The new, more modern Comiskey was built right next door.

Things began to look up for the White Sox in the 21st century. Chicago finally won a World Series title, 86 years after the 1919 Black Sox gave it away. Against Houston, the White Sox won Game #2 of the 2005 World Series at Comiskey on a Scott Posednik homerun in the ninth; Chicago swept the Astros days later. The fans on the south side finally had a champion.

Four years later, veteran White Sox pitcher Mark Buehrle walked to the mound at Comiskey. On July 23, 2009, Buehrle took a perfect game into the 9th inning. Out #27 was dramatically saved by outfielder Dewayne Wise’s acrobatic, over-the-wall catch in center. It was, arguably, the greatest defensive play ever in a perfect game. After a Buehrle strike out for out #28, an on screen television graphic flashed the name and date of the last White Sox perfect game ever thrown: Austin College’s Charlie Robertson on April 30, 1922.

Buehrle got that last out to record the 16th perfect game in league history and the second by a White Sox pitcher. In postgame interviews, the national press asked Buehrle about his thoughts on being the first White Sox pitcher to throw a perfect game since Robertson in 1922. Wise’s effort is honored marked as “The Catch” in center field. White Sox A.J. Pierzinski, who played with Alicia Havnes Henderson‘s husband Scott in the minors, tells a great story about Buehrle’s effort.

In 2012, the New York Yankees still led the majors with most perfect games by an organization. Yankee pitchers had hurled three: Don Larsen, David Wells, and David Cone. However, Philip Humber of the White Sox got the start in Seattle in April 2012, and the former teammate of Alicia’s husband was catching that day. Humber was a former star at Carthage HS (shout out to Chris Medlin and Billy Kuykendall) who played his college ball at Rice and won the final game of the College World Series against Stanford in 2003. That Rice baseball title was the first ever national championship in any team sport for the Rice Owls.

The Rice baseball program counts no less than four Austin College Kangaroos as former Owls skippers (the legendary Wayne Graham is not one). Humber was on fire against the Mariners, and recorded the 19th perfect game in the modern era. With his outing in Seattle, Humber joined Charlie Robertson as the only two Texas natives to throw perfect games. They are also the only two to throw perfectos in the month of April. Umpire Kelly Nutt, the son of former AC Coach Duane Nutt, was behind the plate at Rice in 2003 for more than a few Humber outings.

Unfortunately, the old Comiskey was not transformed into a park like Tiger Stadium or Yankee Stadium after its demolition. It’s now a part of a parking lot for the new stadium. You can, however, visit home plate of the old stadium in the parking lot. Just don’t take any BP please or you’ll smash a windshield. No less than three Austin College Kangaroos graced that parking lot batter’s box in 1924. If an AC grad reading this sends me a selfie from that spot, I’ll post it and declare a fourth.

NO MORE SATURDAY CHARLIE ROBERTSON PREVIEWS FOR A WHILE! The family is headed to London. When we get back, Opening Day will be right around the corner and Robertson’s perfect game will be back.

Arthur Krause was there. The Chicago Cubs fan was at Wrigley Field for Game #3 of the 1932 World Series. Yankees slugger Babe Ruth was at the plate. He pointed towards center field, then proceeded to launch a home run off of Cubs pitcher Charlie Root. New York won the game, and swept the Series one day later. Arthur Krause held on to his Game #3 ticket stub for decades.

The Cubs had been taunting Ruth, and it’s likely the Bambino was gesturing to the Cubs dugout before he launched his famous “called shot.” Nevertheless, the Babe did nothing to suppress the fires of the mythology his home run birthed. When asked if he truly did call his home run, his reply was a cryptic “It’s in the papers, isn’t it?” The call might have been mythology, but the shot was real. It was one of a record 714 home runs for the Sultan of Swat.

The perfect game thrown by Austin College Kangaroo Charlie Robertson was as real as any Babe Ruth blast. On April 30, 1922, Robertson was tapped by White Sox Manager Eddie Collins in Detroit for only the second start of his young career. He then pitched his way into history, throwing only the third perfect game in the modern era against arguably the best hitting team in the history of baseball. Since 1901, only 20 other major league pitchers have equaled the Austin College hurler’s feat.

Robertson, a journeyman pitcher in the 1920s, not surprisingly has history with both Ruth, the man who called his shot, and Root, the pitcher who delivered it.

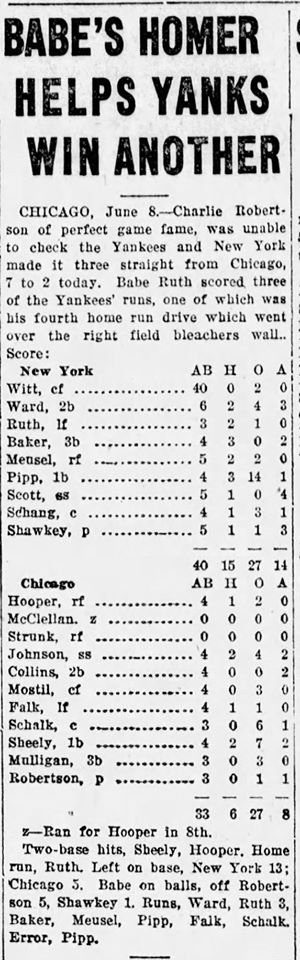

The New York Yankees were in Chicago on June 8, 1922. Robertson, just weeks removed from his perfect game, was called upon to start for the White Sox at Comiskey Park. At the time, he sported a respectable 3.31 ERA with a five wins. One of those wins was his perfect game at Tiger Stadium in Detroit; another was a win over Babe Ruth and New York at Yankee Stadium. But you can only deny the greatest home run hitter in the game for so long. After retiring the first two batters in the first inning, Robertson watched as Ruth walked up to the plate. Robertson dealt, and the Babe was ready. Crack! Home Run. The Kangaroo had just become yet another victim in the Ruth’s path to 714. Robertson went the distance in a 7-2 loss.

Charlie Robertson’s career was plagued by injuries, which eventually forced an early retirement from baseball in 1928. He struggled through that last year with the St. Louis Browns, with only 7 starts for the club. One of those starts came on May 19th, 1928 against the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley, the very ballpark where the Babe would call his shot four years. Facing Robertson on the mound that day was Charlie Root, the very pitcher who would deliver Ruth’s called shot four years later with Arthur Krause watching from the stands. Both pitchers went the distance, but Root got the win. The difference in the Cubs 3-2 victory was an RBI single by pitcher Charlie Root off of Robertson.

It’s Opening Day! The 2019 MLB season begins this afternoon as March turns to April. The month of April will be devoted to Kangaroo Charlie Robertson and his 1922 perfect game in Detroit. The story will be told throughout the month on the following schedule:

3/30: Charlie Robertson Saturday Preview #1

4/6: Charlie Robertson Saturday Preview #2

4/13: Charlie Robertson Saturday Preview #3

4/20: Introduction:

For Love of the Game: The perfect game of Charlie Robertson

4/21: Chapter 1: Inning #1

4/22: Chapter 2: Inning #2

4/23: Chapter 3: Inning #3

4/24: Chapter 4: Inning #4

4/25: Chapter 5: Inning #5

4/26: Chapter 6: Inning #6

4/27: Chapter 7: Inning #7

4/28: Chapter 8: Inning #8

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings:

The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

After watching Ruth call his shot in 1932, Arthur Krause moved to Texas. He raised a son Ken, who played football at Austin college in the 1960s. He welcomed a grandson Kevin, who would shine in Sherman as an all-conference member of Roo baseball in the 1990s. During his time at AC, Kevin Krause called Luckett Hall home. So did Marc Parrish. So did Ken Krause. So did Charlie Robertson. Kevin will be inducted into the Austin College Hall of Honor in August of 2019. Hope to see you there.

Perfect games are rare. Only 21 have been thrown since 1901. That works out to an average of about one every 30,000 pitching starts. Or, alternatively, one every six years. The last pitcher to toss a perfect game was Seattle Mariner Felix Hernandez on August 15th, 2012.

We’ve had some close calls in recent years. Five pitchers have taken a perfect game into the ninth since Hernandez’s outing. All came up short. The most recent near miss was just a few months ago in Minneapolis. On September 8, 2018, Kansas City Royals pitcher Jorge Lopez lost his bid in the ninth with just 3 outs to go. It’s been over six years since the last perfecto; baseball fans are due.

So, like the Bambino, I’m calling my shot. There will be a perfect game thrown in the majors during the 2019 season. Call it Roo Tale magic if you like. When we tell the tale of a perfect game thrown by an Austin College Kangaroo, we’ll get rewarded with an actual perfect game that same year.

Whenever that 2019 perfect game happens, one of y’all come back to this thread and post the news in the comments.

It’s Opening Day! 100 years have passed since Charlie Robertson’s first appearance in the Majors back in 1919. The one constant through those 100 years has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of stream rollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time.

Happy Opening Day everybody. Hope to see you at Legends in August. Should be a fun month of writing in April.

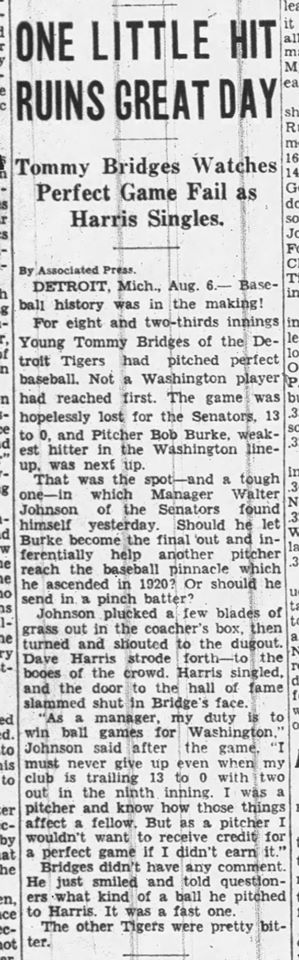

Tommy Bridges was unhittable.

The Detroit Tigers pitcher was having a dominating day at Tiger Stadium. On August 5th, 1932, Bridges took a perfect game against the Washington Senators into the ninth inning. He got the first two batters, and needed just one more out to throw the fourth perfect game since 1901 and the only perfecto since Austin College Kangaroo Charlie Robertson. Robertson’s effort in 1922 had occurred at the exact same park, Tiger Stadium.

Washington Manager Walter Johnson, also one of the greatest pitchers in MLB history, was determined to wreck it. He sent pinch hitter Dave Harris up to bat; Harris was leading the league that year in pinch hits. Harris delivered a single, and Bridges’s effort came up short. The Majors would not see a perfect game for another 24 years, until Yankee Don Larsen finally matched Robertson’s effort in the 1956 World Series.

Pitchers often start strong, and pitch flawless ball in the first three innings. The inevitable mistake comes during innings 4-6; a perfecto headed into the 7th is uncommon. The hurlers who do make it that far will naturally see a walk, blooper, or other imperfection late in the game. The odds are simply turning away from the mound and towards the plate too far too fast.

The pitcher is tiring. His breaking ball is no longer breaking, his fastball does not have any zip, and he’s just trying to get it over the plate and avoid a walk. Meanwhile, the opposition is fired up. No team wants to endure a perfect game, and wrecking an effort is a point of team pride. As the game gets closer to batter #27, the odds of completing get exponentially high.

You won’t be surprised to learn that perfect games broken up in the ninth inning far exceed perfect games completed successfully. Also not surprising: perfect games lost on the final at-bat are common. In fact, the BA of batter #27 in a perfect game exceeds the BA of the majors in 2018. 10 perfect games have been lost on the last batter; that’s a solid 0.323 average for batter #27.

Some of those “wreck it” last at-bats have been memorable.

White Sox pitcher Billy Pierce lost his perfect game in 1958 with one out to go when batter Ed Fitzgerald hit an opposite field double that landed just inches within the foul line. Pierce got a call from Vice-President Richard Nixon the next day, who in spite of being a Senators fan told the hurler that he was rooting for the Sox Ace to go all the way. Pierce’s number has been retired, and his photo appears on the outfield wall at Comiskey Park.

A perfect game by Pierce would have been the first by a White Sox 36 years, since Roo Charlie Robertson in 1922. That second White Sox perfecto finally came from Mark Buehrle in 2009. Buehrle’s effort was substantially aided by an incredible over-the-wall catch by DeWayne Wise in the ninth inning. Wise’s catch is immortalized as “The Catch” in writing on the outfield wall. It sits just above the retired jersey number, photo, and name “Bill Pierce.”