For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

Introduction

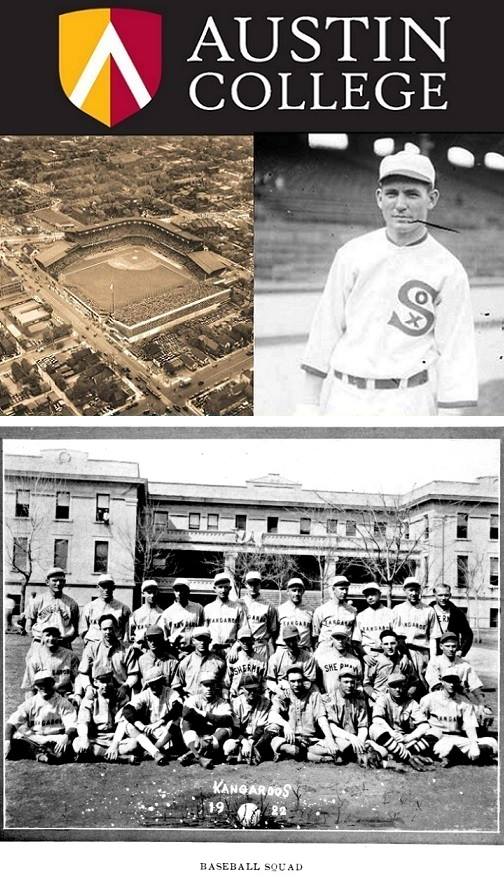

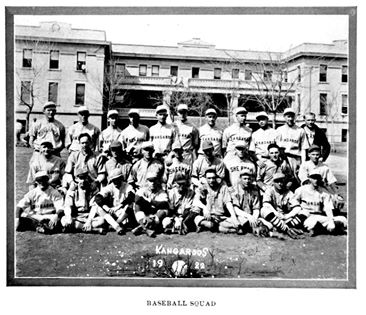

It’s probably my favorite Austin College photo ever.

The picture comes from the 1922 Chromascope, and shows the AC baseball team from that year. It was likely taken around February 1922. The trees in the background display all the signs of winter. AC baseball would have just been getting underway, and probably began with a team photo. Team members are posing in front of Luckett Hall, 15 years after construction and 82 years before demolition.

On the team are future Major Leaguers, including a pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals and a second baseman for the New York Yankees. A good number are headed for the minors as well. Most are wearing their Kangaroo jerseys, though some are sporting “Sherman.” In 1922, it was common to split time between university and club ball. The manager of the 1922 team, Homer Rainey, would later become the President of the University of Texas. He is wearing his “Sherman” jersey and can be found top row, far right.

Then there is the fellow found top row, far left. He’s wearing a “Minneapolis” jersey. That’s Charlie Robertson. The AC hurler had been sent by the Chicago White Sox to the minors in Minneapolis after his 1919 debut. He pitched three years in Minnesota, spending his offseason coaching football and baseball at AC. The major league baseball season would always force a late Sherman arrival for Roo football, and an early Sherman departure from Roo baseball.

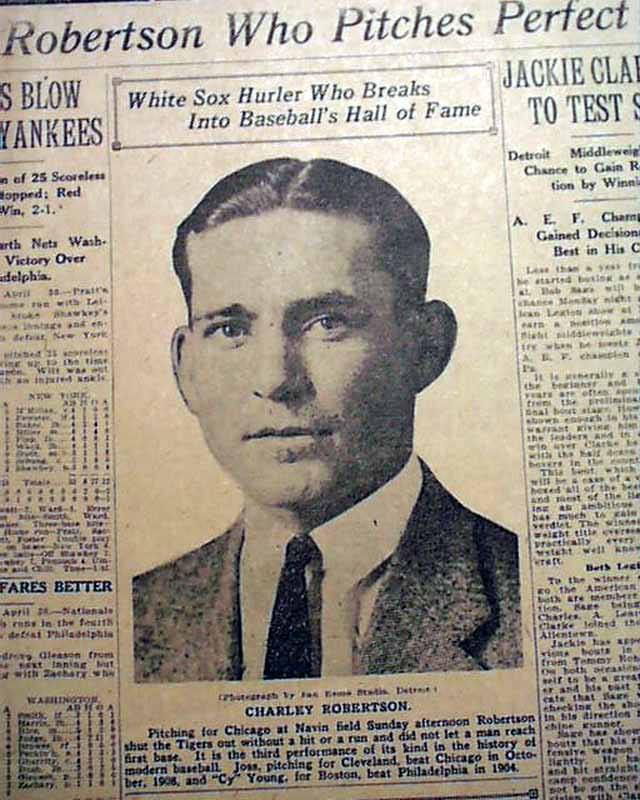

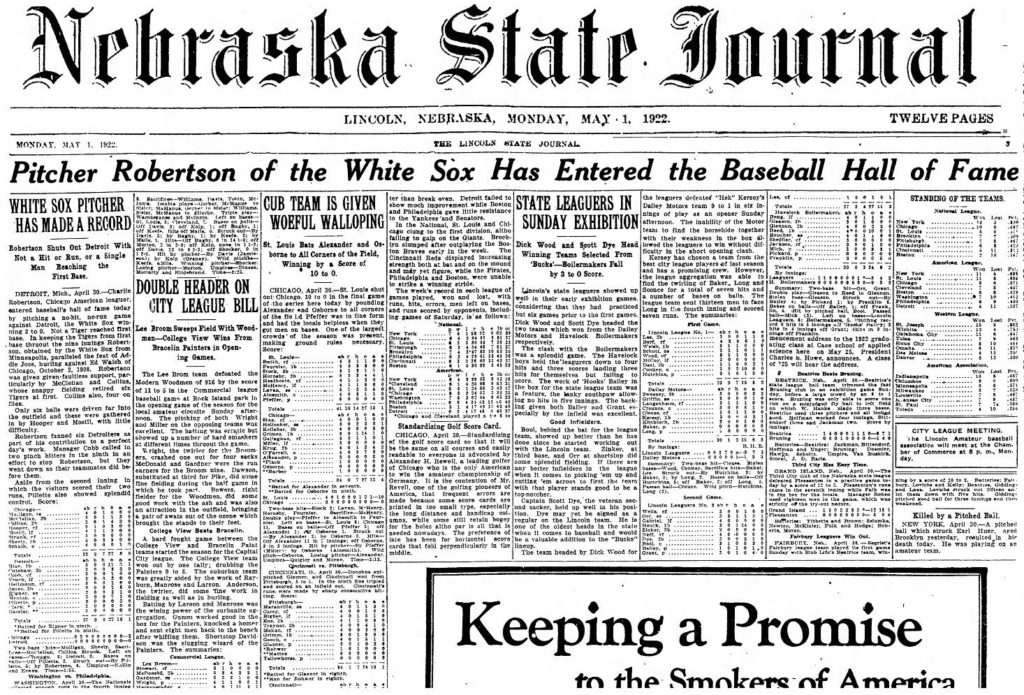

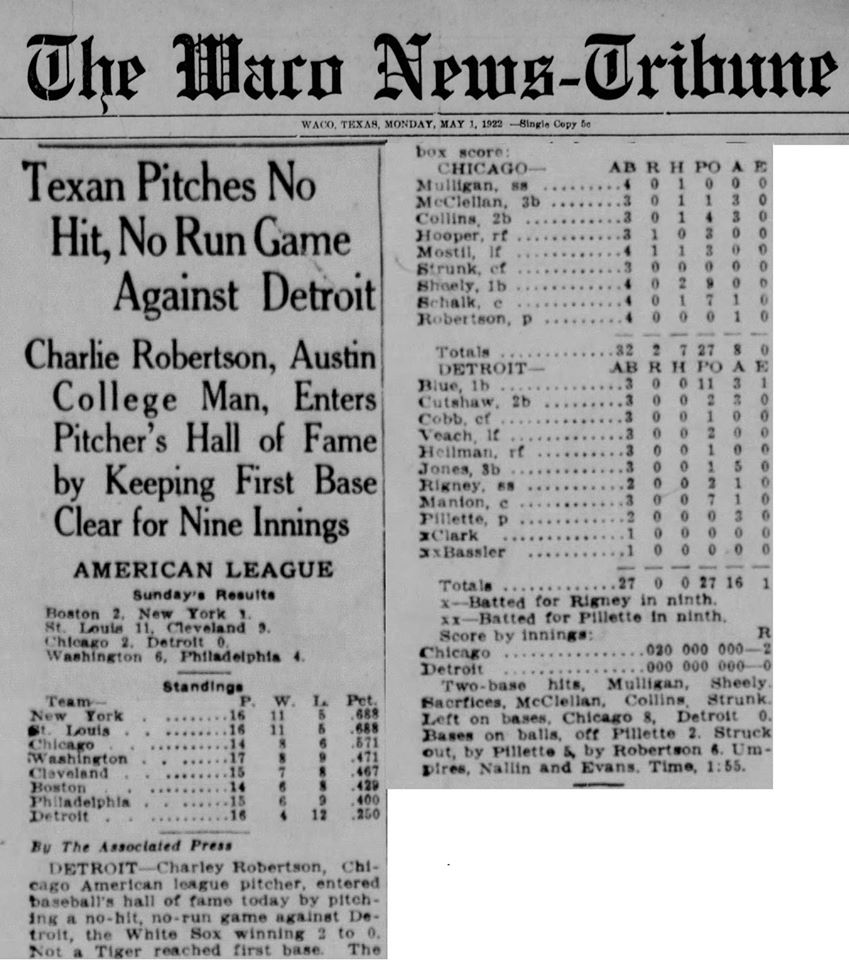

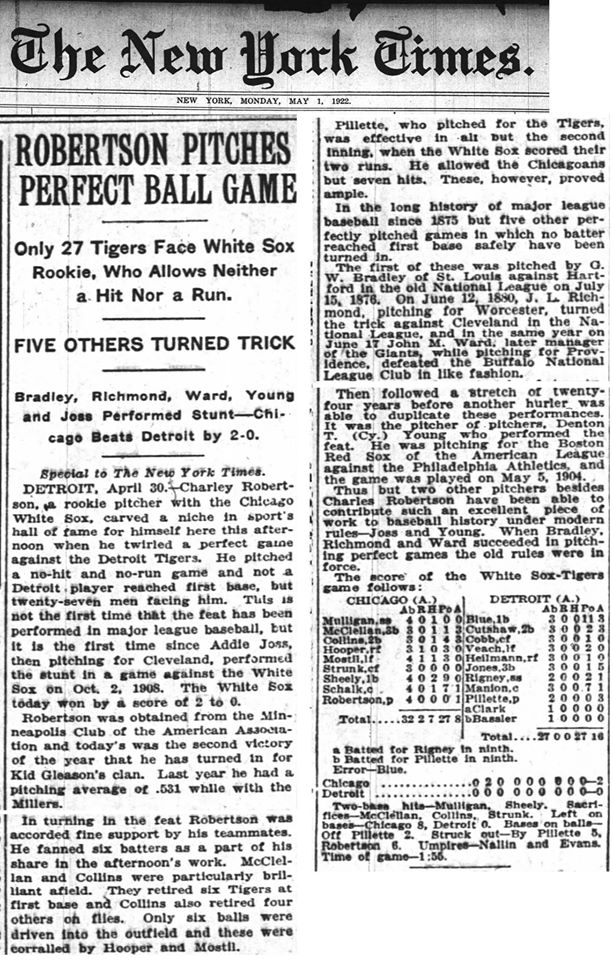

Robertson officially got called back up to the Majors on March 14th, 1922, just days after this photo. He briefly participated in White Sox spring training in Seguin, TX, and then traveled to Chicago with the team just before Opening Day in early April. On April 30, 1922, in only his second professional start, he threw a perfect game in Detroit against Ty Cobb and the Tigers. Only 22 other pitchers have replicated the feat in the majors, and only 20 in the modern era.

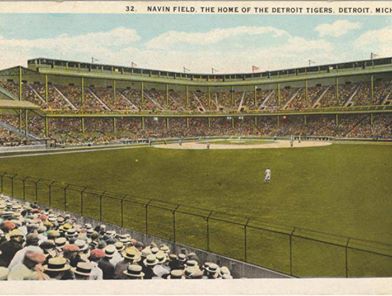

The train carrying the Chicago White Sox team from Cleveland arrived in Detroit on the evening of Thursday, April 27th. Chicago was in town to face the Tigers in a four game series at Navin Field (now Tiger Stadium). Both squads were playing .500 ball and were in the middle of the AL standings, where they’d finish by the end of the season.

The White Sox took the first two games on Friday and Saturday. The Detroit Free Press reported that Tiger Player-Manager Ty Cobb would go with rookie Herman Pillette on Sunday. According to the papers, Manager Kid Gleason of the White Sox was likely to start veteran Shovel Hodge.

He didn’t. Instead, Gleason tapped Austin College Kangaroo rookie Charlie Robertson.

Detroit woke up on April 30th, 1922 to cloudy skies and fair weather. Typical of America during the isolationist, roaring 1920s, the news of the day was often domestic and trivial (President Harding entertains guests) or international and inflammatory (Bolsheviks stoke terror). The temperature was expected to reach a high of 50 degrees: acceptable weather for a stroll to Navin Stadium on Michigan Ave. & Trumbull perhaps, but not to pull off one of the greatest feats in baseball history. Robertson and the White Sox woke up in the Wolverine Hotel downtown, had breakfast, and made their way one mile west to Navin Field to warm up.

That morning, Robertson learned that he’d get the start against the Tigers, who the previous year had set a major league record that still stands today: an incredible team batting average of 0.316. That record was thanks in part to Ty Cobb, the greatest hitter in baseball history. As told by Jacob Pomrenke in his book “Scandal on the South Side:”

“Six of their eight starters in 1922 finished over .300. Even four of their backups hit over .300 that year. They were strong up and down the lineup.”

Originally Bennett Park in 1895, Navin Field was inaugurated in 1912 when owner Frank Navin constructed a stadium around the field to seat 23,000 fans. It opened the same day as Fenway, and just five days after the sinking of the Titanic. April 30, 1922 was a Sunday, a day off for Detroit residents who would often make their way from morning services to an afternoon ballgame. Not surprisingly, an overflow crowd of 25,000 was there to watch the White Sox and Tigers battle.

Robertson arrived at Navin Field, chatted with Gleason in the dugout, and headed to the bullpen to warm up. Robertson felt good that day. Extraordinarily good. Later, he’d remark:

“I never was going better in my life than that day. Everything worked properly. I was able to put the ball right where I wanted it. You see, it was just perfect concentration of mind and body.”

It’s a Roo Tale! It’s called “For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson.” It will be told over the next 10 days on the following schedule:

4/21: Chapter 1: Inning #1

4/22: Chapter 2: Inning #2

4/23: Chapter 3: Inning #3

4/24: Chapter 4: Inning #4

4/25: Chapter 5: Inning #5

4/26: Chapter 6: Inning #6

4/27: Chapter 7: Inning #7

4/28: Chapter 8: Inning #8

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

The story will be told with a little help from the Kevin Costner movie “For Love of the Game.” In the film, an aging pitcher throws a perfect game in his last start in the major leagues. This introduction and every Charlie Robertson chapter going forward will include appropriate clips from the movie in the comments. There is no video of Robertson’s 1922 effort, so scenes from Costner’s 1999 movie will fill in for relief.

Should be a fun way to close out April. See you tomorrow.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

INNING #1:

Play began at 1:55 p.m. Herman Pillette walked to the mound, and the game was soon underway. He got off to a great start, retiring the first three White Sox batters. A rookie for Detroit, Pillette was tasked with facing Charlie Robertson that Sunday; by games end, he would have a solid outing. Pillette scattered 7 hits over a complete 9 innings and gave up only 2 runs. It wouldn’t be nearly enough.

Umpire Dick Nallin was behind the plate. Nallin’s officiating career spanned 18 years in the American league. He umpired the 1927 World Series won by Ruth, Gehrig, and the New York Yankees, and also called Ty Cobb’s last game in 1928. Nallin had called two no-hitters in his career by April 30, 1922, but like nearly all in the majors had never witnessed a perfect game. Only two other pitchers had ever thrown a perfect game since the merger of the National and American Leagues in 1901: Boston’s Cy Young in 1904 & Cleveland’s Addie Joss in 1908.

Behind the plate for Chicago was catcher Ray Schalk. Elected to the baseball hall of fame in 1955, Schalk revolutionized the catcher position into a defensive one. A 10-year veteran known for his camaraderie with pitchers and knowledge of opposing batters, he was the perfect man for Robertson to have behind the plate that Sunday. All day long, Schalk was calling the right pitch and Robertson was executing to perfection.

In the bottom of the 1st, Robertson walked from the third base dugout to the pitching mound at Tiger Stadium. Whatever butterflies Robertson endured in his first start days earlier were gone. This afternoon, he was throwing like a veteran from the very first batter.

Leading off? First baseman Lu Blue.

Luzerne Atwell “Lu” Blue enjoyed a 13-year major league career. He was a switch-hitter with a career on base percentage (OBP) of .402. His best season was his 1921 rookie year in Detroit, when the Tigers set the MLB team batting average (BA) record that still stands. Aided by a strong ability to draw walks, Blue’s OBP in 1921 was an impressive 0.416. Blue was among the league leaders in walks ten times during his career. He credited Ty Cobb with helping him to improve his hitting in the majors.

Blue struck out on a called third strike. One down.

Next up? Second baseman George Cutshaw

Cutshaw’s 12-year major league career was near its end in 1922. He hit 0.267 that year with a respectable 0.300 OBP, not far off of his career average. Cutshaw would have been a welcome addition to any major league lineup outside Detroit. Compared to his 1922 Tiger teammates, however, his ability to get on base was below average.

Cutshaw popped up to second baseman Eddie Collins. Two away.

Batting third: Center Fielder Ty Cobb

Ty Cobb is arguably the best hitter in the history of baseball. His 0.367 career batting average is first all time, and his career 0.433 OBP places Cobb in the top ten. In 1922, Cobb was at the peak of his game. He hit 0.401 that year, one of only 7 players to top the .400 barrier. Cobb was one of the “original six” of the first Hall of Fame class in 1936; his 4,191 hit total was an iconic baseball record until finally broken by Pete Rose in 1984. He’s almost famous for being one of the least pleasant individuals to ever play the game.

After a long at-bat, Robertson got Cobb to ground out to third baseman Hervey McCllellan. Three up, three down.

Both Pillette & Robertson had perfect games going after one inning. Pillette’s perfecto wouldn’t make it past inning #2.

Still to come:

4/22: Chapter 2: Inning #2

4/23: Chapter 3: Inning #3

4/24: Chapter 4: Inning #4

4/25: Chapter 5: Inning #5

4/26: Chapter 6: Inning #6

4/27: Chapter 7: Inning #7

4/28: Chapter 8: Inning #8

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

INNING #2:

The White Sox got after Pillette in the second inning. Right fielder Harry Hooper walked. Backup left fielder Johnny Mostil, substituting for former Longhorn and Robertson friend Bibb Falk, notched a single to right. A sacrifice advanced them both to second & third. First baseman Earl Sheely, who would not have to cover the base all day, singled to left scoring both. Pillette recovered by retiring the side, but the damage was done. Chicago had two runs, more than enough needed that day. Pillette got Robertson to strike out to end the 2nd; Robertson would go 0-4 with three strikeouts on a day that would be remembered for something other than his hitting.

Left Fielder Bobby Veach led off the bottom of the 2nd for Detroit.

Nobody in baseball had more RBIs or extra base hits between 1915 and 1922 than Bobby Veach. The 14-year veteran of the majors hit for both power and average; he had finished second to Ty Cobb for the AL batting title in 1919. Veach’s BA of 0.327 was one of the best seasons of his career. The Detroit outfield of Veach, Cobb, and Heilmann are considered by some historians as the best hitting outfield in baseball history.

Veach got a hold of one, and managed to get a ball pass the infield. However, his pop fly to left field was tracked down by Johnny Mostil. Robertson would allow a ball to the outfield only 5 more times in the game.

Following Veach was right fielder Harry Heilmann.

Heilmann was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1952. He hit a remarkable 0.342 over 17 major league seasons. In 1923, one year after Robertson’s perfect game, Heilmann stole the batting title from Cobb after hitting 0.403. His OBP that same season was an impressive .481; in other words, Harry Heilmann safely reached first base in nearly 1 of every 2 at-bats. His lifetime OBP of 0.409 places him at #36 on the all-time list, just ahead of Jackie Robinson.

Heilmann connected like Veach before him, and launched a shot to right field. Hooper was there for out #5.

Batting sixth: Third baseman Bob Jones

With a career BA of 0.265, Jones was one of the less productive hitters in the Detroit lineup. Over 9 years in Detroit, Jones compiled a career OBP of 0.314 with 791 hits, 208 walks, and 310 RBIs. Jones hit 0.300 only one time in his career, Detroit’s record setting year of 1921. Still, Jones would have found a spot on any other team lineup. His career BA was still nearly 20 points higher than the league average in 2018.

Jones followed Heilmann with a shot to right field. Hooper was able to corral this one as well. One had a sense, however, that the formidable Tiger offense would eventually punch through and make the Roo rookie’s outing a difficult one. Robertson walked to the dugout with six down and a two-run lead. The dangerous Bobb Veach had been retired, but he’d be back.

Still to come:

4/23: Chapter 3: Inning #3

4/24: Chapter 4: Inning #4

4/25: Chapter 5: Inning #5

4/26: Chapter 6: Inning #6

4/27: Chapter 7: Inning #7

4/28: Chapter 8: Inning #8

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

INNING #3:

After a scoreless White Sox third, Robertson returned to the mound to face the bottom of the order for Detroit. Batting seventh was shortstop Topper Rigney.

As a rookie in 1922, Rigney hit 0.300 and recorded an OBP of 0.380. 1922 and 1923 were his most productive years over a six-year major league career. Rigney grew up in Leonard, TX near the Grayson County border. A contemporary of Robertson, he played for a Texas A&M team in 1916 that met the Kangaroos at Kyle Field.

Robertson got Rigney to pop up harmlessly to second.

Next up: Catcher Clyde Mannion.

Mannion’s career BA of 0.218 was one of the lowest on the Tiger team; he was the only member of the starting lineup to hit below the 2018 major league average. However, Mannion had won of his best seasons in 1922, hitting 0.275 with an OBP of 0.315. He ended his 13 years in the majors in 1934 with a career OBP of 0.293, respectable among defensive minded catchers of the era. Even Detroit’s catcher could hit.

Mannion popped up to catcher Ray Schalk in foul territory.

Batting ninth: Pitcher Herman Pillette

Not surprisingly given his pitching role, Pillette was by far the weakest member of the lineup on April 30th, 1922. Pillette hit a poor 0.172 that year with an OBP of only 0.204.

Robertson got Pillette to ground out to third.

Robertson was on a roll. After three innings, Robertson had retired the entire Detroit Tigers lineup once. The odds of accomplishing that feat alone would have been against him. Doing it twice more would be next to impossible.

Still to come:

4/24: Chapter 4: Inning #4

4/25: Chapter 5: Inning #5

4/26: Chapter 6: Inning #6

4/27: Chapter 7: Inning #7

4/28: Chapter 8: Inning #8

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

INNING #4:

Leadoff batter Lu Blue was up again, and struck out just as he had in inning #1. Cutshaw then lined a shot to second baseman Eddie Collins, who easily handled it.

No matter. The best hitter in baseball history calmly walked up to the plate intent on ending Robertson’s effort.

Tyrus Raymond Cobb is rightly considered one of the greatest hitters in the game. For years, the Georgia native has also had a reputation for racial prejudice and a mean streak a mile way. Recent research, however, suggests that the prejudice claims might have been significantly exaggerated because his contemporaries found his demeanor so unpleasant. There’s no denying, however, that he was nearly universally disliked by his peers.

Cobb would give his critics plenty of reasons to not change their minds in the game against Robertson and the White Sox. As the Tiger bats continued to fall silent, Cobb would turn to other, less conventional methods to throw the Kangaroo off his game. Delay, intimidation, and accusation would eventually enter the Detroit lineup. With frustration mounting, Cobb would eventually accuse Robertson of cheating. And consistently, inning after inning.

Amazingly, none of it worked. The rookie pitcher from Sherman, when faced with the outrageous tactics of the best hitter in the game, simply shook it all off like a veteran Cy Young or Walter Johnson. Of Cobb’s antics, Chicago Tribune writer Irving Vaughn would critically write the following of cheating allegations:

“To a spectator it [Cobb’s cheating claims] sounded like the squawk of a trimmed sucker.”

Ty Cobb had hit the ball hard in the first, and was looking to connect in the fourth. He did, and sent a screaming shot to left that forced Johnny Mostil to track it down. But Mostil got under it, and Robertson had retired 12 batters in a row.

Cobb had been retired twice by Robertson, but had plans to help rattle the rookie pitcher and get his Tigers to punch through. And if necessary, he’d have one final shot at-bat against the Roo in the seventh.

After his first at-bat, Cobb was annoyed at the Kangaroo. After his second at-bat, he was enraged.

Still to come:

4/25: Chapter 5: Inning #5

4/26: Chapter 6: Inning #6

4/27: Chapter 7: Inning #7

4/28: Chapter 8: Inning #8

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

INNING #5:

The trouble arrived in the fifth.

Tigers outfielder Bobby Veach had lined a shot to left back in the second inning, but Mostil had tracked it down. In the fifth, Robertson was behind in the count for the first and only time as Veach patiently ran the count to 3-1. He got a pitch he liked grooved down the middle, and tagged a no doubter to right field. From the White Sox dugout, it looked like the future Hall of Famer got all of it. The perfect game was sailing away into the right field stands.

Baseball was a bit different in Detroit back in 1922. Navin Field had a capacity of only 23,000, and Detroit ownership was always looking for ways to sell more tickets. Remarkably, one idea frequently utilized was to sell standing room only tickets on the warning track. The idea was especially popular on Sundays, when more fans could attend. The April 30th game had an overflow crowd of 25,000, which meant the Navin Field warning track was packed with Detroit fans.

The modified rules agreed upon by major league baseball for this situation were straightforward. Any interference by warning track fans on the play of outfielders would be ruled a ground rule double for the batter. This was obviously problematic, in that it created incentives for Detroit fans to stay put when the home team was at the plate. But over time a gentlemen’s understanding developed that warning track fans would avoid outfielders no matter the team.

Veach’s shot to right field suddenly began to fall just short of the wall on the warning track. Right fielder Harry Hooper sprinted towards the fans, hoping that like the Red Sea they would part upon his arrival at the track. They did. Hooper caught the ball on the dead run, hit the wall, turned, and fired back to the infield. Robertson’s perfect game is due in part to the fans of the Detroit Tigers, who cleared a path for Hooper instead of standing their ground.

Heilmann looked to follow Veach’s shot with one of his own, but Robertson had him flustered. The best Heilmann could do was a weak grounder back to the pitcher, who threw and fired to first. With the putout, Robertson was halfway home. Increasingly frustrated, Heilmann then proceeded to do something his Manager Ty Cobb had instructed him to do in the event of an out. He went up to umpire Dick Nallin and requested that the umpire check the ball he had just hit for illegal substances.

Major League baseball had recently banned the use of substances by pitchers, though veterans in the league were grandfathered. Robertson, a rookie, was not one and was required to throw without any assistance from oil, grease, or other lubricant. Heilmann’s request was a subtle accusation of cheating, and was the first of many Cobb efforts to throw Robertson off his game. As the game progressed with no Tiger batter reaching first, the angry accusations and inspection requests would escalate. Nallin failed to find any trace of substance on Heilmann’s ball.

His appeal denied, Jones came up to bat. Robertson forced a pop up in foul territory to third baseman McClellan, and the 5th inning was over. Amazingly, Robertson had retired 15 batters in a row. Given how taxing the late innings are on a perfect game hurler, however, he had in some ways barely even begun.

Besides, Robertson would still have to face Ty Cobb one final time.

Still to come:

4/26: Chapter 6: Inning #6

4/27: Chapter 7: Inning #7

4/28: Chapter 8: Inning #8

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

INNING #6:

Herman Pillette had more than settled down. He retired the side, getting Robertson to ground out to end the top half of the 6th inning. But by then, all eyes were on the bottom half of the inning and Robertson’s flirtation with history. The bottom of the order, the weaker part of the Tigers lineup, was up. Cobb continued to demand that his batters ask Nallin to examine balls for substances. Robertson was unfazed.

The Kangaroo got Rigney to pop up to first in foul territory, then coaxed a groundout to second by catcher Manion. Cobb’s rage and desire to rattle Robertson only increased. The Hall of Famer convinced Nallin to personally join him in a trip to the mound in order to inspect the pitcher’s clothing for substances. If Cobb could not rattle Robertson by inspecting his baseballs, he would humiliate the pitcher by using his clout to enforce a thorough search of his jersey.

Ty Cobb had little reason to be suspicious of cheating, and his inability to find any evidence proves the point. Cobb had other intentions with the interventions. The point of his actions were clear. “Robertson, your performance is a fluke. We are the best hitting team in baseball. You are a rookie. You don’t have the talent. And even if you do, you don’t have the steely nerve to continue. We will force you to falter one way or another. It may be a hit by us. It may be a mistake by you. But this will end.”

Nallin found nothing. “The irrepressible Tyrus inspected all parts of Robertson’s uniform,” wrote Irving Vaughan in the Chicago Tribune. “He was foiled again.”

Pillette was no match for Robertson in a pitcher vs. pitcher duel, and struck out swinging. It was one of six Ks for Robertson on the day. 18 batters in a row had been shut down, and Robertson was perfect after two trips through the lineup. But the top of the order would be up in the 7th, including the great Ty Cobb. Cobb had failed twice before, but was determined not to do so a third time.

Still to come:

4/27: Chapter 7: Inning #7

4/28: Chapter 8: Inning #8

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

INNING #7:

The top of the order was back for Detroit in the 7th, and Robertson was starting to tire. Surely, at long last, the Tigers would break through, end the perfecto, and claw their way back into the game. Blue led off, but could only manage a weak ground out to second. Cutshaw followed with a third base ground out of his own after only a few pitches.

——————————————

“The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Detroit nine that day;

the score stood two to zero, with but three innings more to play.

And then when Blue died at first, and Cutshaw did the same,

a sickly silence fell upon the patrons of the game.”

——————————————

With two outs, up to the plate stepped Ty Cobb. If the Detroit player-manager couldn’t rattle Robertson from the dugout, he’d take of business at the plate.

——————————————

“Then from twenty five thousand throats and more there rose a lusty yell;

it rumbled through the valley, it rattled in the dell;

it knocked upon the mountain and recoiled upon the flat,

for Cobb, mighty Cobb, was advancing to the bat.”

——————————————

Cobb took a called strike one, and backed out of the batter’s box.

——————————————

“And now the leather-covered sphere came hurtling through the air,

and Cobb stood a-watching it in haughty grandeur there.

Close by the sturdy batsman the ball unheeded sped—

“That ain’t my style,” said Cobb. “Strike one,” the umpire said.”

——————————————

He connected on Robertson’s next offering, but sent it foul into the Tiger Field stands.

——————————————

“With a smile of Christian charity great Cobb’s visage shone;

he stilled the rising tumult; he bade the game go on;

he signaled to the pitcher, and once more the spheroid flew;

but Cobb still ignored it, and the umpire said: “Strike two.”

——————————————

With the count 0-2 and Tiger fans on their feet cheering their hometown star, Cobb watched with intense focus as Robertson looked, got the sign, and went into the windup.

——————————————

“The sneer is gone from Cobb’s lip, his teeth are clenched in hate;

he pounds with cruel violence his bat upon the plate.

And now the pitcher holds the ball, and now he lets it go,

and now the air is shattered by the force of Cobb’s blow.”

——————————————

Robertson was a pitcher who primarily relied upon his fastball. According to the Roo hurler though, “everything worked properly” that day in Detroit. “I was able to put the ball right where I wanted it.” As a rookie, Robertson was not familiar with the Tigers lineup. Catcher Ray Schalk was familiar, however, and consistently made the right calls for his rookie pitcher. Robertson’s location on Schalk’s calls never faltered over the course of his 90 total pitches.

Robertson delivered a breaking ball to Cobb, who froze. It caught the corner, and Nallin signaled strike three. Cobb was furious, and began to argue vociferously with the umpire as Robertson slowly walked to the dugout. The Roo had completed 7 perfect innings. Cobb, now 0-for-3 against Robertson, was done. His opportunity to break up the perfect game was over.

——————————————

“Oh, somewhere in this favored land the sun is shining bright;

the band is playing somewhere, and somewhere hearts are light,

and somewhere men are laughing, and somewhere children shout;

but there is no joy in Detroit — mighty Cobb has struck out.”

——————————————

Still to come:

4/28: Chapter 8: Inning #8

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

INNING #8:

In his book “Perfect!”, author James Buckley Jr. points out something interesting. Fans will cheer for the home town team to wreck a perfect game fairly consistently for 7 innings. But in the 8th, they turn. Like clockwork. By the 8th inning, fans of the home town squad suddenly become fans of the game, rooting for the visiting pitcher to accomplish a unique feat in baseball. The same was true on April 30th, 1922. Detroit fans who had been cheering mightily for Cobb to break up Robertson’s perfect game in the 7th inning now switched allegiances, and began rooting for the Roo rookie to finish the job.

As Robertson made his way to the mound in the bottom of the 8th, a huge roar arose from the Tiger faithful. They had made their way to Tiger Stadium on a brisk spring Sunday to see their Tigers win a rather meaningless early season game. Now, they were close to witnessing something that had not been accomplished since the days of Teddy Roosevelt.

From the “Society for American Baseball Research (SABR):”

“The mood of the Detroit crowd changed markedly by the start of the eighth inning. Until then the fans had booed the rookie pitcher with their usual lusty exuberance, but after the Chicago right hander had retired the first 21 Tigers in succession, they did an about-face. Now the Detroiters started pulling for Robertson to complete the rarest of pitching feats.”

Bobby Veach had nearly broken up the perfecto in the fifth. In the 8th, he swung and missed on a 3-2 count. It’s a testament to Robertson’s stuff that two of the best batters in baseball history (Cobb & Veach) both went down on strikes after the Roo had already been perfect through 20 batters.

Now, with just five outs left to go, the crowd began to cheer each strike delivered by Robertson. He got two of them right against the always dangerous Heilmann. The Tiger outfielder made contact on Robertson’s third offering, but weakly popped up to first in foul territory. The most dangerous part of the lineup was retired for good, and Robertson was just four outs away.

Cobb had asked Nallin to inspect Robertson’s baseballs in the fifth. In the sixth, he had joined Nallin at the mound to look over Robertson’s jersey. After striking out in the seventh, the Detroit player-manager became obsessed with doing something…..anything really…..to break up the Kangaroo’s concentration. After Heilmann’s at-bat, Cobb convinced Nallin to take a trip with him to first, where they proceeded to look for substances or color on the glove of first baseman Earl Sheely. Again, no substances or suspicious streaks were uncovered. Cobb’s attempts to break up the rhythm of Robertson were increasingly futile. It seemed nothing could shake Robertson off of his game.

After Cobb returned to the dugout, Jones went up to the plate. He connected on a sharp grounder to second, but Eddie Collins made the play at first. Sheely got the putout with his substance free glove, and the Roo was perfect through eight.

Robertson came up to bat with one out in the ninth. Nobody was on. He had a perfect game going after 8 innings, and was preoccupied with getting just three more outs to reach baseball immortality. Typical for a pitcher, he also wasn’t much of a hitter. In what might have been the least enthusiastic at-bat in baseball history, Robertson struck out. He returned to the dugout, sat on the bench all alone, and continue to maintain the same level of concentration shown in the previous 8 innings.

After out #3 to end the White Sox top of the ninth, his Chicago teammates took the field with anxious enthusiasm. Robertson slowly followed them, making his way to the loneliest spot in the world that day, the pitcher’s mound at Tiger Stadium. All he needed was three more outs.

“Three more, like he’d done a million times.”

Still to come:

4/29: Chapter 9: Inning #9

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

INNING #9:

Happy birthday to me. A Kangaroo is about to throw a perfect game.

Ty Cobb wasn’t going down without a fight. He was 0-for-3 against Robertson, and his Tigers had failed to reach first after 24 batters. The Detroit faithful had turned, and were now rooting for the AC pitcher to claim history with each successive out. The Tigers had the weaker part of the lineup up in the ninth, but Cobb was going to change that.

Leading off the inning, rookie Danny Clark was sent in to pinch hit for a struggling Rigney. Clark struck out. Robertson had K’ed three of the last six batters; remarkably, he seemed to be getting stronger.

With two outs to go, Manion approached the batter’s box. On a 1-1 count, he made contact but failed to get a hold of it. The ball sailed straight up, an easy put out for second baseman Eddie Collins.

And just like that, Robertson was one out away from history. Cobb was determined to wreck it.

Pillette, his starting pitcher, was pulled for backup catcher Johnny Bassler. According to the “Detroit Athletic,” Bassler “excelled at one thing almost better than any other hitter in history – making contact. Four times Bassler hit over 0.300, batting 0.346 in 1924. His penchant for striking the ball came at a cost – he rarely hit for power. But Bassler was a master at getting on base. He posted an OBP over 0.400 in every season he played for Detroit. In 1924 his 0.441 OBP was second only Babe Ruth.”

From “Scandal on the South Side,” by Jacob Pomrenke:

“Robertson called timeout and walked behind the mound to prepare himself. Shortstop Eddie Mulligan was startled to hear Robertson talking to him. ‘Do you realize that little fat man up there is the only thing between me and a perfect game?’ Mulligan was too stunned to reply. He pushed Robertson back toward the mound.”

Robertson was still dealing bullets. He got Bassler on a called strike on pitch #1, and then induced a foul ball from Bassler into the stands on pitch #2. Robertson was one strike away. Bassler then called time.

From “Perfect!”, by James Buckley Jr.:

“After taking a couple of pitches, Bassler himself tried a little trick, halting play to go get a new bat from the dugout. The crowd actually booed its own player, realizing his tactics; the fans wanted to see a perfect game as much as the White Sox did.”

Bassler got his new bat, returned to the box, and dug in.

What’s that old line? If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs, you don’t understand the situation? That was Robertson has he prepared to deliver with the count 0-2. And with a weary body and no doubt a sore arm, the big Tiger crowd of over 25,000 was on its feet and rooting for Charlie Robertson to do the near impossible.

“0-2, the count to Johnny Bassler.”

Robertson delivered.

Bassler swung.

Crack.

It never had a chance.

From “Scandal on the South Side,” by Jacob Pomrenke:

“Bassler’s pop fly to left field settled in Johnny Mostil’s glove just as he passed the left field foul line. A swarm of Detroit fans rushed to congratulate the lanky right-hander and carried him off the field.” It was “an ovation that an athlete seldom is granted on a foreign field,” the Chicago Tribune reported.

From the “Society for American Baseball Research (SABR):”

“Onlookers claimed that they had never heard such a roar for an opposing player. Some of the Detroit fans gave Robertson the ultimate honor when they caught up to the pitcher before he had crossed the base line on the way to the dugout. They hoisted Robertson on their shoulders and carried him off the field.”

Charlie Robertson had pitched a perfect game.

Years later, he spoke about that day to “The Literary Digest:”

“You know,” said Robertson, “it never occurred to me that I was nearing the big thing until after two men were out in the ninth inning. Then, when Cobb sent up a pinch hitter, it suddenly dawned on me that I was standing right on the brink of the thing. It made me feel a bit funny, and I wondered if the rest of the fellows realized the fact.”

“I was just wrapped up in working each batter as he came up. I’d look at him, figure out who he was, and then remember what it was he was supposed to have pitched to him. Then I’d bend my efforts towards putting what he was supposed to be unable to hit up there where he could swing at it. No, even the business of having Cobb and his players feel my glove and trousers and things didn’t bring me to a full realization of what was going on.”

“And you know the superstition of the thing prevented anybody from saying anything on the bench. So my feelings on the matter were almost confined to after the game, when I will say I was pretty excited.”

“There has been a lot of stuff printed about the way Cobb acted in that game. And I think this ought to be told. I had the honor of being the guest of the Intervarsity Club of Detroit a while after I pitched that game and sat at the table with Cobb. And he told me then, personally, that he had never seen more ‘stuff’ on a ball in his life and that that was the reason why he kept looking at it. And he added that whatever talk there had been aroused about his protesting the game was all false; that as far as he was concerned he had been licked fair and square and that was the end of it all.”

Charlie Robertson’s perfect game is one of the least well-known in Major League Baseball history. It was thrown before the age of media by a journeyman pitcher who left the game behind after retirement. And yet, it is probably the most remarkable.

From “Perfect!”, by James Buckley Jr.:

“A perfect game in his fourth start? Against Ty Cobb & Co.? The gem tossed by Charlie Robertson in 1922 sounds like something dreamed up for a Hollywood script. Hollywood wouldn’t buy this script. Oh wait, maybe it would. Kevin Costner’s character pitched a perfect game in ‘For Love of the Game.’”

Major League Baseball historian John Thorn probably sums it up better than anyone:

“Robertson’s total dominance led historian John Thorn to call his performance ‘perhaps the most perfect game ever pitched.’”

Happy birthday to me. A Kangaroo just threw a perfect game.

Still to come:

4/30: Chapter 10: Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

For Love of the Game: The Perfect Game of Roo Charlie Robertson:

Extra Innings – The anniversary of Robertson’s April 30, 1922 perfect game.

On this date in 1922, an Austin College Kangaroo threw a perfect game.

It’s only been done 21 times since 1901. That infrequency should give the reader a clue just how rare the feat is. 30 teams in the majors, 162 games in a season, 2 starters per game, and 118 seasons since the merger of the National and American Leagues. Even non-math majors can quickly determine that a perfect game is baseball’s version of Halley’s Comet. Very few states, let alone alma maters, can claim a perfect game pitcher as one’s own. Amazingly, Austin College can.

And what a perfect game.

From “Perfect!”, by James Buckley Jr.:

“A perfect game in his fourth start? Against Ty Cobb & Co.? The gem tossed by Charlie Robertson in 1922 sounds like something dreamed up for a Hollywood script. Hollywood wouldn’t buy this script. Oh wait, maybe it would. Kevin Costner’s character pitched a perfect game in ‘For Love of the Game.’”

Kevin Costner is famous for his baseball movies. One of them, “Field of Dreams,” celebrates its 30th anniversary this spring. It’s full of easily recognizable scenes and quotes. There’s one that applies to Charlie Robertson.

The story of Charlie Robertson is part inspiration and part tragedy. His perfect game should have put him permanently in the rarified air of baseball immortality. Pitchers who throw perfect games today immediately become a part of baseball history and are celebrated as such. But not Charlie Robertson. His name is not recognizable to anyone except for the truest of baseball historians.

Robertson’s perfect game came before the era of television mass media, which would have brought his performance into the homes of millions. His perfect game came during the reserve clause days of baseball, which meant that he’d never be truly compensated for that day or his career. His perfecto came under the ownership of Charles Comiskey, a man notorious for refusing to compensate his players appropriately. Indeed, Robertson’s 1919 teammates, the infamous “Black Sox,” were so fed up that they were willing to throw a World Series to right that wrong. Many of Robertson’s “Eight Men Out” teammates show up in Costner’s Field of Dreams, including the great Shoeless Joe Jackson.

Robertson could have at least had the glory of his alma mater, but an angry dispute after an unfair demand by Austin College administration left Sherman in his rear view mirror. It’s quite possible that Robertson’s perfect game celebrity was his downfall. He briefly became a ticket selling name, which led to overuse by Comiskey and the injuries which ended his career prematurely.

That “name” could well have been what drove AC administration to demand that Robertson return to campus permanently or not at all. By the time the Great Depression hit, Robertson was done with both baseball and Austin College. When Yankee Don Larsen finally threw his perfect game in the 1956 World Series, Robertson had moved on completely. “Just forget about my game. It was a long time ago,” he told reporters.

I don’t believe those words. As he watched baseball grow in size and stature from the 1950s to the 1980s, I believe Robertson would have preferred a re-write, one where he is appropriately recognized for his outstanding performance on April 30, 1922 by Major League Baseball.

In the movie Field of Dreams, Doc “Moonlight” Graham gets his wish granted. Graham (played by Burt Lancaster) was called up to the majors and played one inning of one game in the major leagues. However, he never got to bat. After being sent down and toiling in the minors, Graham gave it all up and became a successful doctor in Minnesota. Yet he never lost that dream of facing down a major league pitcher. In the movie, Graham finally gets that wish. His sacrifice fly in the movie does not count as an official at-bat, and the record books remain untarnished.

All of Robertson’s 1919 teammates are there on the field as Graham is at the plate. Chick Gandil, Buck Weaver, Swede Risberg. Eddie Cicotte pitches to Graham. And Shoeless Joe Jackson gives him the advice needed to get the bat on the ball. Later in the movie, a medical emergency requires Graham to end his dream. He can never go back. But it’s ok. He thanks Robertson’s teammates and tells them to win one for him one day. As he disappears into the corn, Jackson yells out: “hey rookie, you were good!”

When you write about someone, you get close to them. You feel their frustrations, and you want to make things right. Robertson deserved better. Yes, his life was a long and quite possibly a rewarding one. But there is still a missing chapter. The one where his contributions to baseball are matched in return by the game.

I now know his story, and there will probably be opportunities for recognition. The 100th anniversary of the outing will occur in three years, and I plan on continuing to write to make his effort more widely known in baseball circles. Maybe those efforts will turn into a collective effort to give Robertson what he deserved yet failed to receive during his lifetime. A loud and clear shout out from baseball, saying:

“Hey rookie, you were good.”

Hope you enjoyed this Roo Tale! You better believe there is more to come from a Texas school that is 170 years old.