How is a Roo Tale born?

It depends. Sometimes, it’s because of all y’all. One of you may write or share something relevant. Maybe you message me about it, or maybe I just happen to read about it. Then, others will add their own related story or experience. Next thing you know, whole groups of folks are writing and the topic grows. Meanwhile, I’m in the back drinking it all in. I start to do some digging of my own. And I begin to wonder. Will all of this reading and research reach a critical mass? An actual story?

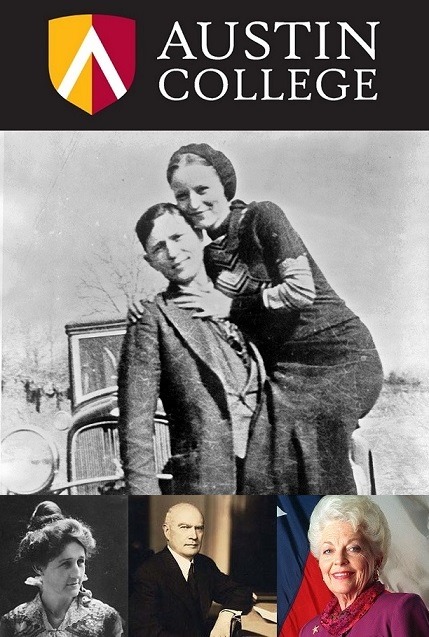

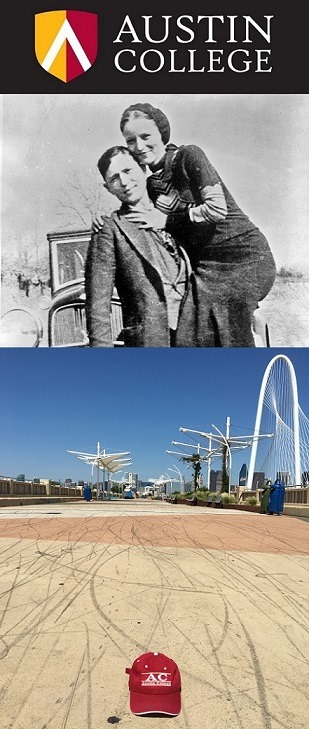

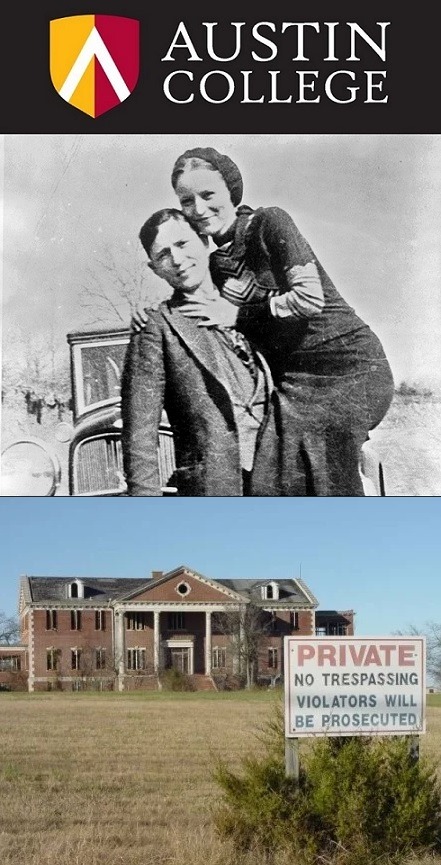

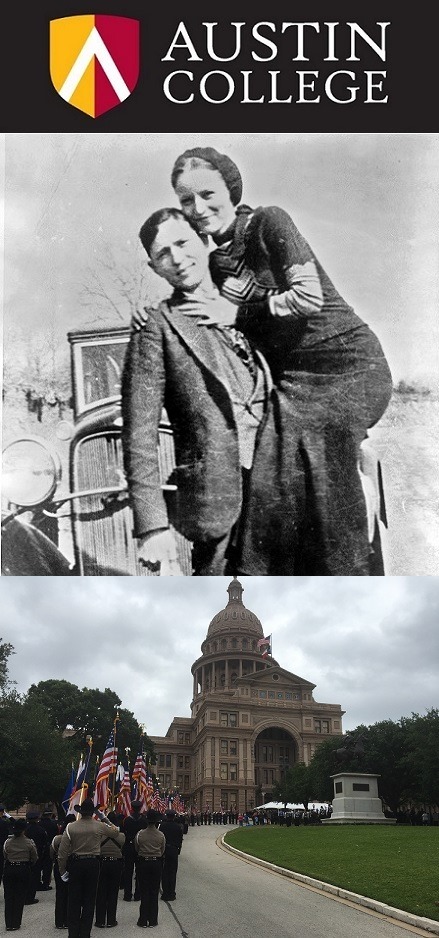

A few months ago, Claude Webb Jr. shared a book about Frank Hamer, a person I had only briefly heard of. It looked like my kind of thing, so I bought the book and read it. Claude shared the book because of a recently released movie about Hamer’s role in the story of Bonnie and Clyde.

A week or so later, Tom Nuckols and Ruth Nuckols Cox Williamson shared an article about an individual with ties to the subject of Claude’s book. That individual? He’s an Austin College Kangaroo. The article was the work of former AC professor Light Cummins, who knows a thing or two about history.

That article led to other sources where Dr. Cummins is quoted. Reading eventually led me to yet another book. Next thing I know, I’m paging through that book at the Harry Ransom Center on the campus of the University of Texas.

And of course, all of this eventually led to digging of my own. More Roo ties began to show up, even to Roo Tales I’ve already written. Eventually, that critical mass was met; we’ve got ourselves a story. We’ve also got ourselves yet another reminder. If the story is Texas, Austin College is probably going to be a supporting actor.

Austin College is a small liberal arts school in a small town in Texas, surrounded by large universities and metropolitan areas in a large country. The place is quiet and small. But Austin College does have one thing other schools don’t. It’s OLD. And that means it’s got stories, from a time when universities, cities, and the country itself just weren’t so big and in such a damn hurry. Those 170 years since 1849? That’s unique among Texas institutions.

I’ve already started writing, and I like it so far. It’ll be a good one. I’d recommend watching the movie “The Highwaymen” on Netflix to prepare for this latest “Roo Tale Jan Term.” 🙂.

The tale is called:

“Roo Ties Everywhere: Austin College and the Legend of Bonnie and Clyde.”

If you are fascinated by the story of Bonnie, Clyde and the Texans on their trail, you’ll enjoy. Your own related stories on the subject are of course welcome as well! Why? Because Roo Tales often wouldn’t happen otherwise. Roo Tales are born because of y’all. Whether you know it or not.

Thanks to Claude, Tom, Ruth, and Light for getting me started.

The scholarship interview had just concluded, and I was chatting with members of the Hatton W. Sumners board on the campus of Austin College. It was the spring of 1990, and we talked about the recently held Democratic primary for Governor which Ann Richards had won. I was fortunate to be selected as a recipient of a Sumners Scholarship weeks later. Given to students in the discipline of political science, the scholarship is awarded by the Hatton W. Sumners foundation to four students at Austin College.

Back in 1990, I wasn’t sure if I’d win it. However, I had no doubt who would win in 1991. The award would surely go to one of the smartest PolySci students at AC: Shannon Harpold Hutcheson. 1991 took me to Spain for a year abroad, where I learned of the general election win by Richards and the Sumners scholarship win by Hutcheson. I didn’t know what the future held for Shannon, but it was bound to be inspiring. I was certainly going to watch. That same year, Richards was inaugurated as the second woman governor in Texas history.

The first woman governor in Texas, Ma Ferguson, had her hands full. Ferguson, who had won her first term as Governor by defeating an Austin College Kangaroo, was well into her second term by 1934. In spite of the best efforts of Texas and neighboring states, law enforcement was simply unable to reel in outlaws Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow. After the Huntsville prison break in January of 1934, Ferguson had seen enough. She tasked Austin College’s Lee Simmons, head of the prison, with finding them. Simmons convinced Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, a close friend of fellow Ranger and Austin College Trustee P.B. Hill, to take the job. It wouldn’t be easy.

By the spring of 1934, Hamer had growing confidence. He had secured agreement with a Barrow gang family member to betray the group in exchange for a pardon. He had lulled Barrow into a false sense of security by staying away from that family member’s home in Louisiana. Hamer had determined the best spot to confront the gang: a high point on a lonely road leading to the family home. He had even figured out a way to get Barrow to briefly slow down or even stop his stolen V-8 Ford. Hamer was this close to coaxing either a surrender or the “end of the line.”

But he had one finally problem: Barrow gang weaponry.

In the 1930s, law enforcement was overwhelmingly a state enterprise. Only Texas, or states like Louisiana with whom Texas partnered, had the authority to act. Texas law enforcement, however, did not have access to the high powered, Browning fully automatic rifles (BARs) that had been recently invented (and which today are wisely banned from sale to the public). Bonnie & Clyde certainly had access; the two frequently stole these weapons from federal armories. In more than a few instances, the duo had been cornered by law enforcement, only to escape because authorities could not match the fusillade. One confrontation in Stringtown, OK saw the gang shooting its way south into Texas past Austin College; another confrontation in Sowers, TX saw the gang shooting its way north into Oklahoma past Austin College once again. The Barrows had family in Grayson County, who frequently assisted.

Federal authorities obviously had the firepower that Texas did not. The Barrow gang was stealing and using the best the fed armories had to offer. Texas law enforcement requests to federal authorities for access to the same armaments, however, were consistently denied. That was until Ma Ferguson, Lee Simmons, and Frank Hamer got assistance from a Texas Congressman in Washington.

From “Go Down Together: the true untold story of Bonnie & Clyde,” by Jeff Guinn:

“Heavier ordnance was needed. Hamer, Lee Simmons, or Smoot Schmid contacted Weldon Dowis, the commander of the Texas National Guard unit with jurisdiction over the state armory in Dallas, and asked that two BARs be loaned to the posse. It was always simple for Clyde to break into armories and steal all the BARs he wanted, but Dowis didn’t make it easy for the lawmen to be similarly armed. He said the weapons in the armory’s arsenal were for Guard use and turned down the request. But after Texas congressman Hatton Sumners intervened, Dowis reluctantly issued a pair of BARs to Hamer and his men.”

With the help of Sumners, the anarchy of the Barrow gang soon came to an end. Simmons, who had been fundraising for Austin College just months earlier, reported the end of the line to Governor Ferguson in May of 1934.

Texas has had two female governors in its history: Ma Ferguson, who finally ended Bonnie & Clyde’s mayhem, and Ann Richards, who was inaugurated when Shannon Harpold Hutcheson became a Sumners Scholar. Would Shannon make a fine Governor herself? I would have said “absolutely” in 1990, and would do so with even more enthusiasm today.

But Shannon’s not running for Governor. Like Hatton W. Sumners before her, Shannon is running for Congress. She kicked off her campaign for TX-10 this week.

The next Roo Tale is still being written. The story is called:

“Roo Ties Everywhere: Austin College and the Legend of Bonnie and Clyde.”

More Bonnie & Clyde previews to come.

Chapter 1: Ma Ferguson & George Butte

Chapter 2: Lee Simmons & Lile Bustard

Chapter 3: Frank Hamer & P.B. Hill

Chapter 4: Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow

Chapter 5: Eastham

Chapter 6: Easter

Chapter 7: End of the Line

Chapter 8: Epilogue

Shannon? Go get ‘em my friend.

US Highway 69 snakes its way north from Greenville, TX. It enters Grayson County just south of Whitewright, and continues on towards the Red River. Just miles from Oklahoma, it turns west and makes its way to Denison, TX and the much more traveled US Highway 75. Highway 69 is fairly good route for those wanting to head north undetected.

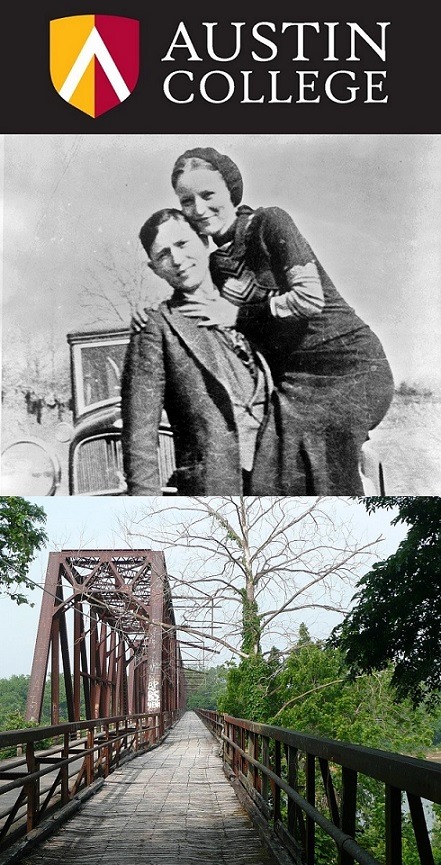

There’s even a Red River crossing available for those seeking anonymity. Carpenter’s Bluff bridge. Situated just a few miles from the Highway 69 westward bend, the bridge is the “road less traveled” option to the Sooner state. My Austin College fraternity? We were certainly familiar with that rural Grayson County bridge.

We’d head out to the bridge in the predawn hours of every single Bid Night before taking a new class. The tradition began before I arrived in Sherman, and continues off and on to this day. Back in 1990, it was a challenge to get to the darn thing the middle of the night. The drive to the bridge felt a bit like Burt Reynolds and Jon Voight trying to find the Chattooga River in the movie “Deliverance.” Where were we goin’ city boys? It was nothing but the biggest river in the dang staaaate.

But we found the bridge in 1990, just as we did in years to come. We walked the bridge that morning, enjoyed an adult beverage, took a picture, listened to the river, and maybe even saw the sun start to rise. Later that night, we took in the class of 1990 and celebrated the arrival of a new group that would one day visit the bridge themselves.

That bridge on the river is a part of our college experience. Turns out, that bridge has a lot of history.

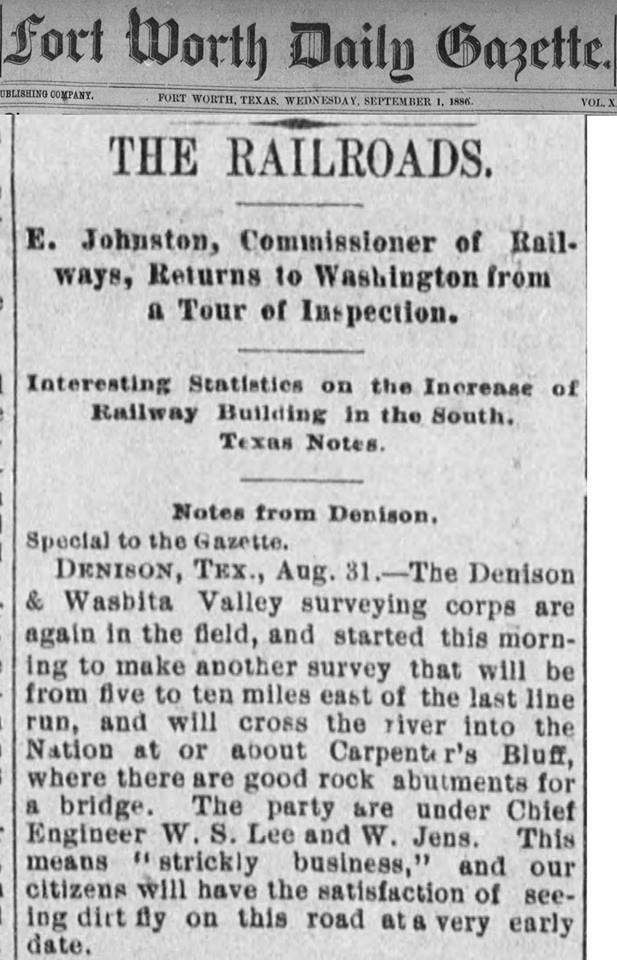

The railroads were interested in a bridge at Carpenter’s Bluff as early as the 1870s. The Fort Worth Gazette mentioned in 1886 that survey crews were considering a bridge which “will cross the river into the Nation (Oklahoma) at or about Carpenter’s Bluff, where there are good rock abutments for a bridge.” The dream finally became a reality in 1910, when the railway bridge was inaugurated and the first train crossed. Grayson County, already fully integrated by rail with other Texas towns, was now permanently linked with the territory that would later become the state of Oklahoma.

The new bridge accommodated trains quite well. But what about automobiles? Carpenter’s Bluff bridge had a single rail line, and the explosion of automobiles after WW1 led to demands for accommodation. The railroad which owned the bridge responded, by constructing a narrow, somewhat precarious, wooden planked lane alongside the rail line. The planks could only accommodate one car at a time, and speeds had to be extremely slow. But by 1929, automobiles could make the crossing into Oklahoma.

That was awfully convenient for Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow.

The crimes of Bonnie & Clyde took the couple across the country for the better part of three years in the early 1930s. Most of their travel, however, centered on the triangle connecting Texas, Missouri, and Louisiana. By far the trip between Texas & Oklahoma saw the most miles, usually because the duo was fleeing yet another crime. And often, that crime involved a confrontation with law enforcement.

The Barrow gang got reckless in Stringtown, OK in August of 1932. An avoidable confrontation led to the death of Deputy Eugene Moore, the first of nine officers killed by the gang. Barrow and Parker fled south, crossed the Red River at Grayson County, and made it back home to the anonymity of West Dallas.

Dallas Sherriff Smoot Schmid was sure he had Clyde Barrow trapped in Sowers, TX in November 1933. But Barrow’s sixth sense saved the group again. The gang was able to flee, and made their way north across the Red River again. Because jurisdiction ended at state lines, bridges like Carpenter’s Bluff were sought after destinations by Barrow.

On Easter Sunday of 1934, Bonnie, Clyde and a third gang member murdered Texas Highway Patrolmen H.D. Murphy and Ed Wheeler in Grapevine, TX. The killings shocked the country, and turned Depression era public opinion decisively against the gang. By April of 1934, Governor Ma Ferguson had already tasked Austin College’s Lee Simmons with hiring the Ranger who would put an end to Bonnie & Clyde’s outlaw status.

The efforts of that Ranger, Frank Hamer, had already intensified dramatically. After the Grapevine killings, Hamer and partner Mannie Gault pursued the gang through Grayson County into Oklahoma, even spotting them briefly in Durant, OK. It was a violation of their jurisdiction, but nobody cared. Certainly not Governor Ma Ferguson, who just wanted Bonnie & Clyde off the road. In the movie “The Highwaymen,” Hamer (Kevin Costner) and Gault (Woody Harrelson) cross the Red River on the hunt. The scene also includes Governor Ferguson (Kathy Bates) berating Austin College Kangaroo Lee Simmons (John Carroll Lynch) about his inability to keep tabs on Hamer. See the comments.

Clyde Barrow was famous for his handling of his V-8 Ford and his ability to drive dramatically long distances. He was also an expert on small farm-to-market roads and less traveled highways. Barrow used this knowledge to avoid law enforcement and the public eye. US Highway 69 was a favorite on trips into and out of his home of West Dallas. In 1933, Barrow said goodbye once again to his family in Dallas and headed north.

From “Go Down Together: The True, Untold story of Bonnie & Clyde,” by Jeff Guinn:

“So they said goodbye, and Clyde sped away down Eagle Ford (now Singleton) Road. Every moment they weren’t moving was dangerous. They headed north out of Texas again. Clyde apparently like driving on Highway 69, which rolled smoothly all the way through Kansas into Minnesota.”

More than anything, safe passage between his Texas home and the border states north was what Bonnie & Clyde needed most. State troopers were more likely to monitor the major thruways over the river. But a rural rail bridge with a rickety planked auto lane in pre-dawn hours was a much less risky choice. Time and time again, Bonnie & Clyde would make their way to Carpenter’s Bluff and cross the Red River. Sometimes north, sometimes south, always on the run.

Carpenter’s Bluff bridge is much easier to reach today. A well-traveled road can be taken directly from Denison, TX to the river. Just last year, the bridge got a neighbor. A new, modern, wide bridge specific for cars was finally completed. Fortunately, there are no plans to demolish Carpenter’s Bluff bridge. It will be converted into pedestrian only.

We were all there at Carpenter’s Bluff bridge in the predawn hours of February 1990. It was cold, and we walked the rickety planks used by Bonnie and Clyde a half century earlier. We returned to Sherman, and celebrated the arrival of a new fraternity class that evening.

One of the members of that 1990 class, Reggie Smith, is now a Representative in the Texas House. His House District #62 includes all of Grayson County.

Which means that Reggie’s district also includes…………..Carpenter’s Bluff bridge.

The next Roo Tale is still being written. The story is called:

“Roo Ties Everywhere: Austin College and the Legend of Bonnie and Clyde.”

Chapter 1: Ma Ferguson & George Butte

Chapter 2: Lee Simmons & Lile Bustard

Chapter 3: Frank Hamer & P.B. Hill

Chapter 4: Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow

Chapter 5: Eastham

Chapter 6: Easter

Chapter 7: End of the Line

Chapter 8: Epilogue

More Bonnie & Clyde previews to come. Thanks Sridhar Yaratha for the Carpenter’s Bluff photos. Share your own Carpenter’s Bluff photos and stories below; we’d love to read.

What drove Bonnie & Clyde to an outlaw life of mayhem and murder?

The poor choices of the two are certainly to blame. Most people, no matter their lot in life, do not elect a life of anarchy and death. The Huntsville Penitentiary of Austin College Kangaroo Lee Simmons deserves its own share as well. Barrow family members consistently claimed that Clyde left Huntsville a hardened and malevolent man, after enduring hard labor and sexual abuse following a theft conviction.

But without a doubt, the economic disparities in Dallas played a significant role. West Dallas is found just a mile or two west of downtown, across the Trinity River. Back in 1932, it might as well have been a million.

The Barrows and the Parkers were raised in West Dallas in the 1920s. The only positive thing to say about a childhood in this predominantly white neighborhood is that the residents at least had it better than the African American communities south of town. Otherwise known derogatively as the “Devil’s Back Porch,” West Dallas struggled through the Roaring Twenties. When the Great Depression hit rock bottom 1932, those struggles became unbearable suffering. That year coincided with Barrow’s release from Huntsville and the beginning of his 28-month life as a fugitive.

West Dallas struggles were often worsened by Dallas sheriffs and the mayors with whom they partnered. Dallas sheriff Smoot Schmid was determined to earn the glory of capturing the two. However, it was Schmid’s office, and that of his predecessors, which are frequently blamed for the law enforcement overzealousness that nudged much of West Dallas into the very lawlessness they were attempting to curb.

The Lamar-McKinney Bridge was opened to traffic in 1932. It connected downtown with West Dallas, and was utilized frequently by Schmid and deputies to travel across the Trinity and keep tabs on the locals in the Devil’s Back Porch. The bridge was also used a good deal by Bonnie & Clyde, who always seemed to be able to quietly return to family in West Dallas all the while avoiding the authorities. Until the “end of the line” in May of 1934 anyway.

Simmons was authorized by Governor Ma Ferguson to hire two Texas Rangers to end Bonnie & Clyde’s outlaw status. In the movie “The Highwaymen,” Frank Hamer (Kevin Costner) and Manny Gault (Woody Harrelson) travel through West Dallas to do some reconnaissance. They pass by the Parker household, as well as the Barrow family gas station on Eagle Ford (now Singleton) Road. “And I thought my circumstances were bad,” says Gault.

The Great Depression era economic disparities explained Bonnie & Clyde’s popularity, at least initially. In a world where greedy bankers were foreclosing on desperate tenant farmers like the family of Tom Joad, Americans were feeling wrath and were going to root for the Joads. Even if that meant tolerating a little violent crime. The reaction wasn’t necessarily a rational one, but understandable given the unimaginable suffering at the time. In “The Highwaymen,” Hamer leaves Kangaroo Lee Simmons in Austin after getting his assignment. Heading out of town, he spots a rural Texas water tower. It reads “Go Bonnie & Clyde.”

The federal public goods (pensions, education, health) and activist monetary policy which followed the Great Depression did much to lessen the suffering of places like West Dallas. So did the enfranchisement of previously powerless communities, and the arrival of local Dallas leaders emphasizing coalition-building instead of confrontation. Leaders like Ron Kirk.

Ron Kirk was elected the mayor of Dallas in 1995 with 62% of the vote, thanks in part to the support of the Dallas business community, minority communities, and struggling areas such as West Dallas. Kirk’s Trinity River Project saw the construction of parks and highways along the Trinity River, furthering the integration of West Dallas with downtown. Kirk was re-elected in 1999 with 74% of the vote total. He resigned in 2001 in order to run for a U.S. Senate seat. I’m proud to say I cast a vote for him.

Ron Kirk is also an Austin College Kangaroo, Class of ’76.

I traveled from Austin to Dallas last month for an Austin College Athletics “A” Board meeting. I arrived early, so that I could briefly stop by West Dallas. What’s left of the old Barrow family gas station still sits on Singleton Road, as does the location of the Parker home where the gang would communicate by way of a message in a bottle. Herbert street, where Bonnie & Clyde first met, offers a nice view of downtown. I passed by all of these spots, and then made my way to North Dallas for the meeting. I crossed the majestic Hunt Bridge, yet another part of Kirk’s Trinity River Project.

What’s the best way to get from downtown to the West Dallas neighborhood of Bonnie & Clyde? You might choose the new Hunt bridge in all of its glory. But me? I’ll take the old Lamar-McKinney Bridge that Bonnie & Clyde preferred back in the early 1930s. After 84 years, the Lamar-McKinney Bridge was converted to pedestrian only in 2016.

It was also renamed: The Ronald Kirk Pedestrian Bridge.

The next Roo Tale is still being written. The story is called:

“Roo Ties Everywhere: Austin College and the Legend of Bonnie and Clyde.”

Chapter 1: Ma Ferguson & George Butte

Chapter 2: Lee Simmons & Lile Bustard

Chapter 3: Frank Hamer & P.B. Hill

Chapter 4: Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow

Chapter 5: Eastham

Chapter 6: Easter

Chapter 7: End of the Line

Chapter 8: Epilogue

Tried to find my old Ron Kirk Senate 2002 yard sign in the attic, but came up empty. 😊 I’m looking forward to meeting Mr. Kirk one day in Sherman, Dallas, or Austin.

More Bonnie & Clyde previews to come.

The Communications/Inquiry (C/I) class that first year students take at Austin College is in part designed to transition new Roos to their new home. Mine worked in a similar manner. Our student leaders were Amber Mcgregor (swimming) and Otis Amy (football), both of whom sit in the Austin College Athletics Hall of Honor. John Talley (football) and Elon Werner (basketball) were in that class. I hope to see both this summer when Jason Johnson (football) is inducted into the AC Hall.

That fall, we were all slowly getting to know everybody and figuring out what to do for a little fun in Sherman, TX. Football games were a must, and off campus parties were frequent. We learned of all-you-can-eat at Track’s and MG’s after a day of ultimate frisbee. I played golf with Kevin Krause at the cheapest place a couple of poor students could find: Grayson County College golf course. The course no longer exists, but Kevin is still hitting them long and straight. Kevin Krause (baseball) will also be inducted into the AC Hall this summer. Hope to see you there.

Some days the entertainment was unconventional. One weekend that fall, a couple of C/I fellas came up to me with an odd idea for a weekend experience:

“We’re headed at midnight to check out an abandoned, haunted orphanage. Wanna come?”

Well, sure. Sounded more like a brush with Grayson County’s finest than anything else. But Sherman was new and I would have probably done about anything to get to know folks in the first semester at my new home.

We headed west on Hwy 56, stopping just before FM 1417. There, on the right, were a couple of huge buildings in the dark. No lights, no cars, no signs of life. We made our way with flashlights and walked into the place. Broken windows were the norm and the rooms showed all the signs of years of decay. Yet it was remarkably intact. There were plenty of abandoned souvenirs for the taking.

Yet, why would I want a souvenir from this place? Where the hell was I?

Turns out, it really was an orphanage.

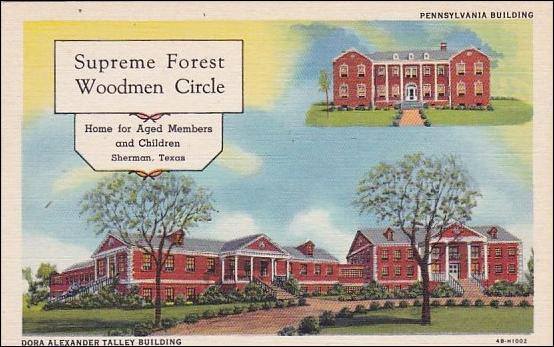

The Woodmen of the World Life Insurance Society was formed in 1890 in Omaha, NE, and today continues to occupy a Woodmen Tower in that city. Founded by Joseph Cullen Root, the organization found opportunity in philanthropic efforts. At the turn of the century, life insurance was the exclusive province of males. Root saw both injustice and a market.

The Woodmen company began offering policies for women, orphans, and families, and soon found their revenue growing rapidly. During a time when federal and state social budgets were small, this life insurance company in Nebraska was often the difference between stability and destitution for many women and children. Yet for one woman, the policies were still not enough.

Dora Alexander Talley was a Texas native living in Omaha with family ties to the Woodmen company. Talley became committed to the establishment of an actual home for widows and orphans, funded by a “fraternal beneficiary association” to be created by the company. Her efforts bore fruit after World War 1. All that was left to do was to find a location for the home. Given the size and scope of the project, there was solicitation by cities from Chicago to Dallas.

In the end, the “Woodmen Circle Home” would settle on little Sherman, TX as the site of the orphanage. This decision was due primarily to the hard work and persistence of one Sherman man.

Lee Simmons. The guy who ended the crime spree of outlaws Bonnie & Clyde.

Lee Simmons was the Marshall of the Huntsville state prison in the 1930s. Simmons was tasked by Governor Ma Ferguson with ending the anarchy of the infamous duo after their January 1934 prison break in Huntsville. He hired Frank Hamer to find the two; four months later, Hamer called Simmons to give him the news. The mayhem was over.

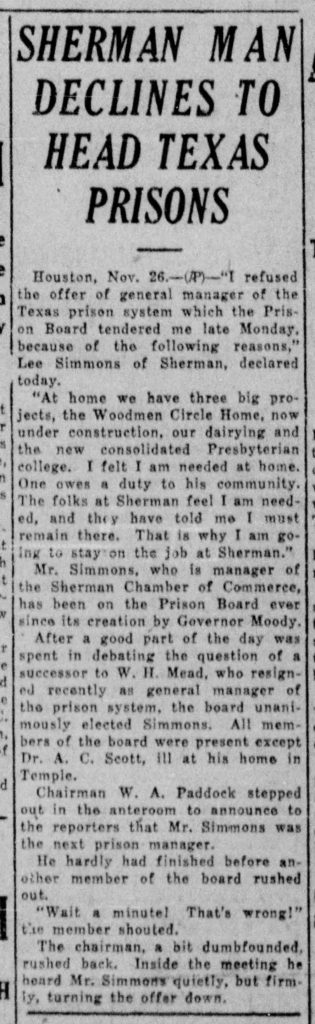

Before Huntsville though, Simmons was a prominent citizen of Grayson County. His family had moved to Sherman in the 1900s; Simmons attended two years at Austin College before graduating from the University of Texas in Austin. He then returned home and served two terms as Grayson County Sheriff in the 1910s, before establishing a banking career in Sherman by the 1920s.

Towards the end of that decade, his pursuits became more community oriented. Simmons began to raise funds for Austin College athletics, and was master of ceremonies when the new Cashion Field athletic facility was dedicated in 1924. He increasingly collaborated with local charities. He also became the driving force on the Sherman Chamber of Commerce.

Simmons was asked by Governor Dan Moody to head the state prison in 1929. He declined, stating the following projects at home for his reasons to stay:

“At home we have big projects. Among them, the Woodmen Circle Home now under construction and the newly consolidated Presbyterian College (All Women’s Texas Presbyterian College in Milford merged into AC in 1929…hat tip to Marc Daniel). I felt I am needed at home. One owes a duty to his community. The folks at Sherman feel I am needed, and they have told me I must remain there.”

By 1930, things had changed. The orphanage opened, and TPC’s incorporation into Austin College was complete. Lee Simmons was asked again by the Governor to head to Huntsville. He accepted.

In his book “Assignment Huntsville: Memoirs of a Texas prison official,” Simmons makes it clear. After decades of business and community activities in Grayson County, the one thing that he was most proud of was landing the Woodmen Circle Home Orphanage.

Dora Alexander Talley didn’t make it easy. As an executive in the “fraternal beneficiary association,” Talley enjoyed traveling the country and having city elites flatter her in order to win her vote. In his book, Simmons mentions that his engagement with Talley and other Woodmen took years. Again and again he thought he had secured Sherman as the site for the home, only to learn that Talley was still undecided. Simmons was relentless, however, and pursued the orphanage with the same vigor he and Hamer showed looking for Bonnie & Clyde. Finally, in 1928, the Woodmen made it official. Sherman had won. Construction began on the home at the corner of 56 & 1417. The orphanage opened in 1930.

It could not have come at a better time.

The Great Depression hit America hard, and America’s powerless hardest of all. With few public goods (pensions, health, education, etc.) to speak of, places like Bonnie & Clyde’s West Dallas and Simmons’s East Sherman began to suffer. The hundreds of women and children who occupied the stately Woodmen Circle Orphanage, however, had a refuge. These families escaped the worst the 1930s had to offer.

Eventually the Depression gave way to a post war boom fueled by New Deal activism. The introduction of national public pensions (Social Security) combined with efforts at the state level to care for abandoned children reduced the need for private initiatives such as the Woodmen Circle Home. The number of residents began to dwindle, from hundreds in the 1940s to tens in the 1960s. The orphanage was closed in 1970.

Fifty years later, the edifice still stands, slowly decaying from within and providing entertainment of dubious legality for many AC students over that time. The current ownership has dreams to restore the place, but admits that restoration would be a tall and questionable task.

I know I’m not the only Roo to visit the orphanage. If you are reading this, you probably paid a visit too. Share your story. Heck, given the number of times the two had to travel on backroads from Dallas to NE Oklahoma, I’m betting the place was even briefly viewed by Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow.

The next Roo Tale is just about done. Let’s wrap up these previews and get this tale going. The story is called:

“Roo Ties Everywhere: Austin College and the Legend of Bonnie and Clyde.”

Chapter 1: Ma Ferguson & George Butte

Chapter 2: Lee Simmons & Lile Bustard

Chapter 3: Frank Hamer & P.B. Hill

Chapter 4: Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow

Chapter 5: Eastham

Chapter 6: Easter

Chapter 7: End of the Line

Have a good weekend everybody.

Last month, I took a short walk from my office to the Texas State Capitol building.

The office of UT System Administration where Roo John Cotton and I both work sits on the corner of 7th and Lavaca, the exact location of the First Presbyterian Church founded by Daniel Baker and his son William in 1850. A man named Abner Cook oversaw construction of that first Baker church at 7th and Lavaca. A year earlier, both Baker and Cook were in Huntsville; Baker was overseeing the establishment of Austin College and Cook was supervising the construction of the new state prison.

Three blocks north I passed the Governor’s mansion. It was here that Governor Ma Ferguson coordinated with state prison head (and former Austin College Kangaroo) Lee Simmons in 1934. Their problem was straightforward: how best to get outlaws Bonnie & Clyde off of Texas roads. The Texas Governor’s Mansion was constructed in 1854, also by Abner Cook.

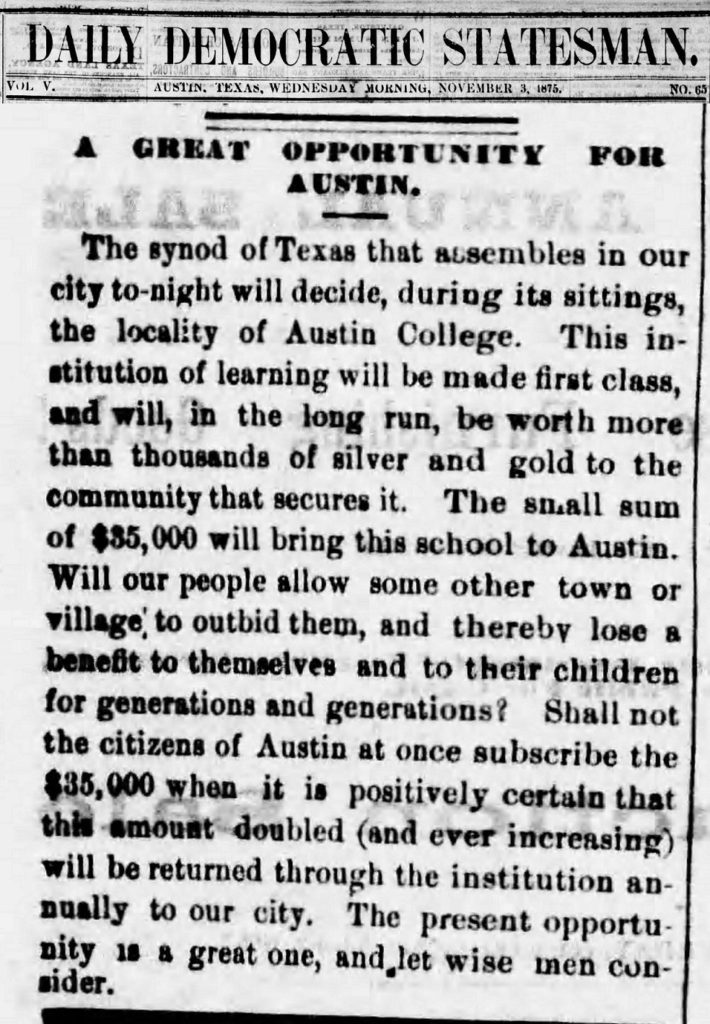

I crossed 11th street and arrived at the State Capitol. Designed in 1881, Austin College was by that year over three decades old; AC had already rejected an offer for relocation to the city of Austin 6 years earlier. From the November 3, 1875 edition of the Austin Statesman:

“The synod of Texas that assembles in our city tonight will decide, during its sittings, the locality of Austin College. This institution of learning will be made first class, and will, in the long run, be worth more than thousands of silver and gold to the community that secures it. The small sum of $35,000 will bring this school to Austin. Will our people allow some other town of village to outbid them, and thereby lose a benefit to themselves and to their children for generations?”

I was headed to the State Capitol to watch an annual event: the Memorial Ceremony for Texas Peace Officers. The current Governor was there. I suspect state legislators (and former Roos) John Bucy and Reggie Smith were present as well. 21 Texas Peace Officers who died in the line of duty in 2018 were honored.

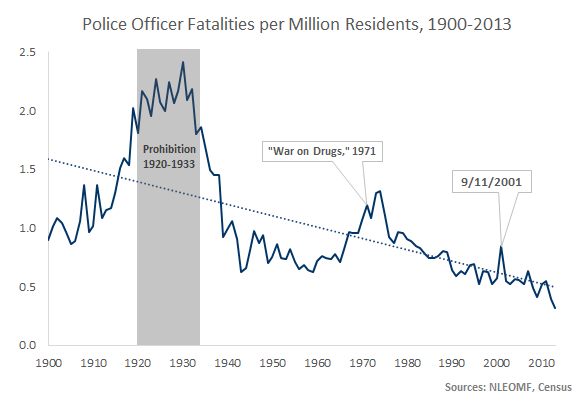

The death of one Texas Peace Officer, or any person for that matter, is of course a tragedy. Nevertheless, there’s never been a safer time to be in law enforcement. Officer fatalities rates nationwide are down by 60% since 1970, and have fallen a remarkable 90% since the Great Depression. The decade of the 1930s were an incredibly bleak time, when poverty and violence lurked behind every corner.

The decline in officer deaths has mirrored an incredible fall in violent crime rates itself. It’s a success story that is rarely talked about. President Kennedy once remarked that “success has a million fathers, yet failure is an orphan.” The dramatic decline in violent crime seems to buck that trend. There is often political advantage by powerful interests in denying this reality, and rank-and-file Americans don’t seem to find the good news terribly interesting. The explanations for the recent fall (lead) are varied (lead!) and widely debated (it’s LEAD people), and the most likely explanation is not terribly sexy.

Whatever the reasons, there’s no denying that the 1930s were a desperate time for both Texas and the country. Crime, lawlessness, state violence, and poverty were so extreme that they threatened to unravel the entire social fabric of this nation. A significant amount of American culture comes from these desperate times. Music (“This Land is Your Land”), literature (“Grapes of Wrath”), and movies (1939 may be the most celebrated year in cinematic history) all come from this tumultuous decade. So does the story of Bonnie & Clyde.

The infamous duo were celebrated as Robin Hood heroes and also cursed as immoral villains. The authorities which pursued them were supported by patriotic citizenry and also angrily accused of the austerity induced suffering which caused Bonnie & Clyde to be partially adored in the first place. It was a complicated and miserable time, and it’s no surprise that Americans heartily welcomed that post WW2 stability that eventually arrived.

The story of Bonnie & Clyde is overwhelmingly a Texas tale. Not surprisingly, that makes it also an Austin College tale. This next Roo Tale is all done, and will be told in 7 chapters over the next 7 days. It’s called:

“Roo Ties Everywhere: Austin College and the Legend of Bonnie and Clyde.”

Chapter 1: Ma Ferguson & George Butte

Chapter 2: Lee Simmons & Lile Bustard

Chapter 3: Frank Hamer & P.B. Hill

Chapter 4: Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow

Chapter 5: Eastham

Chapter 6: Easter

Chapter 7: End of the Line

See you tomorrow.

https://www.fox7austin.com/news/fallen-officers-honored-at-texas-peace-officers-memorial-ceremony