Introduction:

College football was born on Thanksgiving Day, 1893.

Technically, not true. The game officially traces its roots to the 1869 Rutgers – Harvard matchup in New Jersey. The 1875 Tufts – Harvard game is likely the first instance of the “game as we know it today.” The arrival of the Harvard – Yale rivalry in the 1880s made it a permanent feature of the American landscape.

Nevertheless, college football remained a very subdued affair for the nearly three decades after the end of the Civil War. Interest was limited to students, faculty, alumni, and families.

That changed dramatically on November 30, 1893.

Yale sat atop the football world. No team had been able to defeat the Bulldogs in three long years, and only once had the team been scored upon during that span. Yale marched through the 1893 season with few challenges, outscoring the opposition 336-6 over 10 games.

But Princeton had a fine team of its own, and the Tigers ended their season with a matchup against Yale. As the school from New Jersey continued to mow down one team after another, it became clear that the 1893 season finale might be something special.

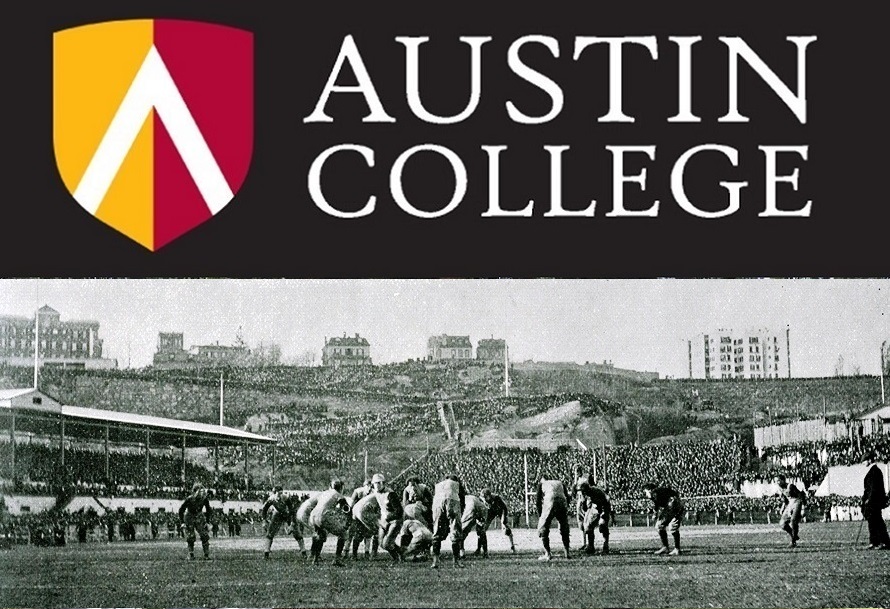

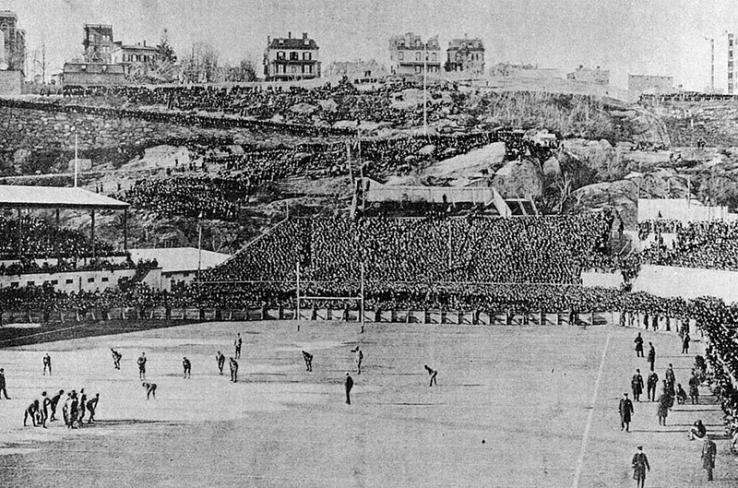

Both schools agreed to move that final game to the Polo Grounds in New York City. The Polo Grounds were located in Manhattan, just west of the Harlem river not far from present day Yankee Stadium. Until their demolition in 1964, the Grounds were a fixture of the New York City sporting world for nearly a century. A key feature of the area was Coogan’s Bluff, a 160-foot rise that allowed spectators to watch the game from afar free of charge.

The Polo Grounds sat just 70 miles from both schools in New Jersey and Connecticut, allowing easy day access for students, family, and fans. By scheduling on the Thanksgiving holiday, residents of New York City were also able to attend. And did they ever. There was a huge amount of attention payed to the game in the New York press in the days before Thanksgiving. Everyone, it seemed, wanted to be a part of the excitement and catch this historic game.

In his book “The Opening Kickoff: The Tumultuous Birth of a Football Nation,” Dave Revsine provides the details:

“One of the year’s most anticipated social events, the championship game was a place for high-society New Yorkers to see and be seen. It was an age when conspicuous displays of wealth were becoming more and more acceptable, and the Thanksgiving game was the perfect time to show off, as the Vanderbilts and the Whitneys used the contest as a convenient excuse to spend and celebrate. Their activities were breathlessly described in New York’s powerful and ubiquitous newspapers, which spread the gospel of the event to the masses.”

“‘No one who does not live in New York can understand how completely it colors and lays its hold upon that city,’ famed journalist Richard Harding Davis wrote in 1893 of the Thanksgiving Day game. ‘It, in short, became the thing to do, and the significance of that day once centered in New England around a grateful family offering thanks for blessings received and a fruitful harvest now centers in Harlem about twenty-two very dirty and very earnest young men who are trying to force a leather ball over a whitewashed line.”

The New York Herald joined in:

“No longer is the day one of thanksgiving to the Giver of all good. The kicker now is king and the people bow down to him.”

From the New York Times:

“It is not what the Puritans made it, and while the traditional name cannot be easily displaced…it has plainly lost its old meaning. Suggestions of a new designation would be timely, but football day will not do.”

As Ron Burgundy would say, it was kind of a big deal.

40,000 fans showed up for the clash in Upper Manhattan. It was BY FAR the largest crowd ever to watch a football game in America. The Gilded Age WASP elite had premium seats in the stands, while Irish and Italian immigrants who need not apply for such seats instead fought for a good spot on Coogan’s Bluff. There, they all watch a titanic battle between two heavyweights.

Revsine again:

“And the truth was, it was dramatic. The anticipation was so great that as Princeton prepared to kick off to Yale, a remarkable hush came over the throng. They had waited for this for so long, talked about it so much, and now, it was finally here. The tension was almost too much to bear.”

Princeton ended Yale’s run. The Tigers scored a first half touchdown, and their defense kept the Yalies from mounting any serious scoring threat in the second half. The streak was over. When the game was finally called as the sun began to set, pandemonium broke out amongst the Princeton faithful.

From Revsine:

“Broadway was jammed with delirious Princeton fans, waving flags and twirling their hats on their canes, all the while screaming Tiger yells. By early evening the sidewalk was so clogged with revelers that they spilled out onto the street, making it impossible for carriages to pass.”

“In all, it was a day that felt much more like a modern college game than like that first intercollegiate contest between Rutgers and Princeton. What had begun as an informal, gentlemanly pursuit between students of rival universities was well on its way to becoming a thrilling nationwide spectacle.”

Photos of the game survive. The teams can be seen battling on the field, with thousands watching from the stands. Even more impressive are the tens of thousands scattered on Coogan’s Bluff, desperate to see some of the spectacle.

As those photos were taken, they were also playing football down in the great state of Texas.

The University of Texas Longhorns had officially formed its first ever team in 1893, and had accepted an invitation by a local Dallas “Heavyweights” club to face off in a game at Fair Park (near the present day Cotton Bowl). The Heavyweights, a group of working class men, declared themselves to be the “Champions of Texas” and were expected to easily defeat this new team of erudite university men. The game itself was, at a much smaller scale, every bit the spectacle of the game in Manhattan.

All of Dallas society made their way to Fair Park to take in the game. Women fought for and won the right to view the contest, and they showed in their Sunday best. Dallas elites assured themselves of the best premium seats, while the rank-and-file jostled for a place behind the end zone. In a dramatic upset, the University boys from Austin shocked the squad from Dallas. They returned home victors who had ushered in the first game in Longhorn history and the first game, arguably, in the state of Texas.

With the Longhorn win on Thanksgiving Day, 1893, football was here to stay in the Lone Star state.

==========================

It’s one of the most famous lines from “The Empire Strikes Back.” As Luke leaves Yoda’s training to rescue his friends, an image of Obi-Wan mentions to Yoda that Skywalker is “our last hope.” Yoda quietly responds:

“No. There is another.”

At the time of Princeton-Yale game on that Thanksgiving Day, there were TWO football games taking place in the state of Texas. One was the historic Longhorn victory at Fair Park in Dallas, which allowed UT to debatably claim itself as the “first” to play college football in the state of Texas.

But…..

“There is another.”

It’s a Roo Tale!

There are 148 schools of higher education in the state of Texas. Most of them trace either their founding or their participation in college athletics to the 20th century. There are only five Texas schools who trace both to the 19th century. This story will go back in time to the 1800s and tell the story of the arrival of the game at these five historic schools in Texas.

The story will be told in 7 Chapters. It’s titled: “The Birth of Texas College Football.”

9/30 Chapter 1:

Baylor 1899: The Bears and the Revivalry

10/1 Chapter 2:

TCU 1896: Horned Frogs join the party

10/2 Chapter 3:

Austin College 1896: Kangaroos officially make it three

10/3 Chapter 4:

Texas A&M 1894: Aggies and the Thanksgiving Day rivalry

10/4 Chapter 5:

Texas 1893: Longhorns and the Birth of Texas College Football

10/5 Chapter 6:

Wait, What???

10/6 Chapter 7:

Austin College 1893: Kangaroos and the Birth of Texas College Football

Chapter 1 begins tomorrow. See you tomorrow.

https://www.frankhinkey.com/1893-Yale-vs-Princeton.php

https://www.amazon.com/Opening-Kickoff-Tumultuous-Football-Nation/dp/0762791772

The Birth of Texas College Football

Chapter 1: Baylor 1899: The Bears and the Revivalry

In 1896, Harvey Carroll traveled to Mclennan County to promote football on the campus of Baylor. Carroll, the son of the chairman of the Baylor Board of Trustees, had become a fan of the game as a graduate student at the University of Texas. He was determined to bring the game to Waco. The Baylor student body requested that the faculty allow a football team at Baylor that same year.

Baylor faculty turned them down, however, as they felt that the students were being “too hasty.” They did it again in 1897, even though every male student at Baylor had signed a petition pleading with administration to change course.

By 1897, football was already played by four Texas colleges. UT had started their program years earlier. Brazos river rival Texas A&M had as well. Austin College in Sherman was already suiting up. Even crosstown rival TCU had a team. In the 19th century, TCU was located in west Waco; the move to Fort Worth would come in 1910.

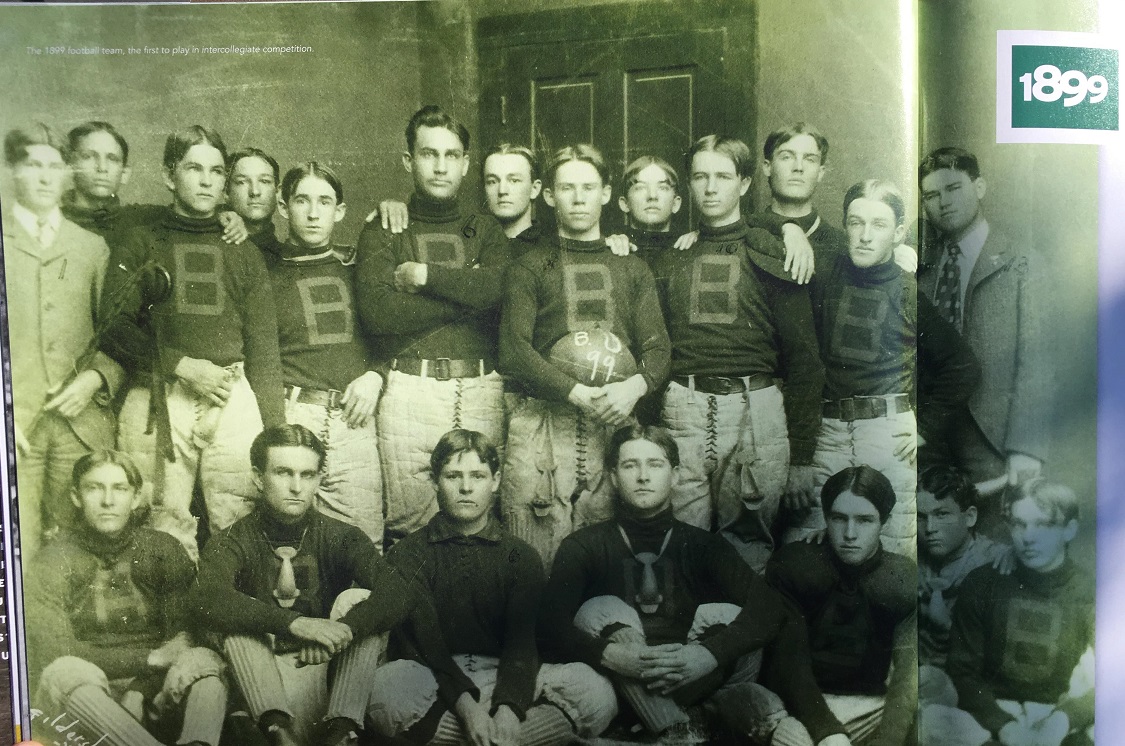

After years of observing intramural contests and the popularity of the sport on other campuses, Baylor administration finally relented. In 1899, Baylor officially had its first football team, and the fifth in the state of Texas. That first season consisted of four home games, all at home.

That season included the birth of the “Battle of the Brazos.” Texas A&M, with its five-year old football program, traveled north from Bryan to Waco and met Baylor on campus in an unknown field called the “West End.” The stadium had a capacity of 1,000, and was referred to at least once as “the best gridiron in Texas.” A&M won easily, 33-0. In “The History of Baylor Sports,” author Alan J. Lefever noted that the loss “showed the first-year program that there was still much room for improvement.” Lefever is a mutual FB friend of Austin College Kangaroo & Baylor Bear graduate Tim Corwin.

The 1899 Baylor Bulldogs (“Bears” would come later) redeemed themselves, however, with a season ending tie against crosstown rival TCU. The “Christians” had been playing ball for three years; that experience, however, was not enough to earn a win. The first edition of the “Revivalry” ground to a standstill between the schools that stood just two miles apart.

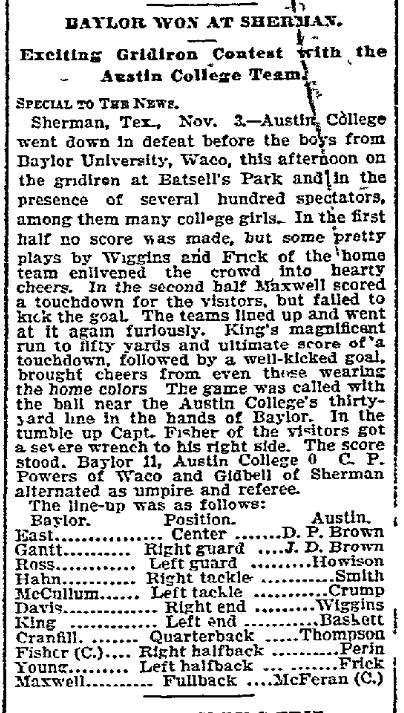

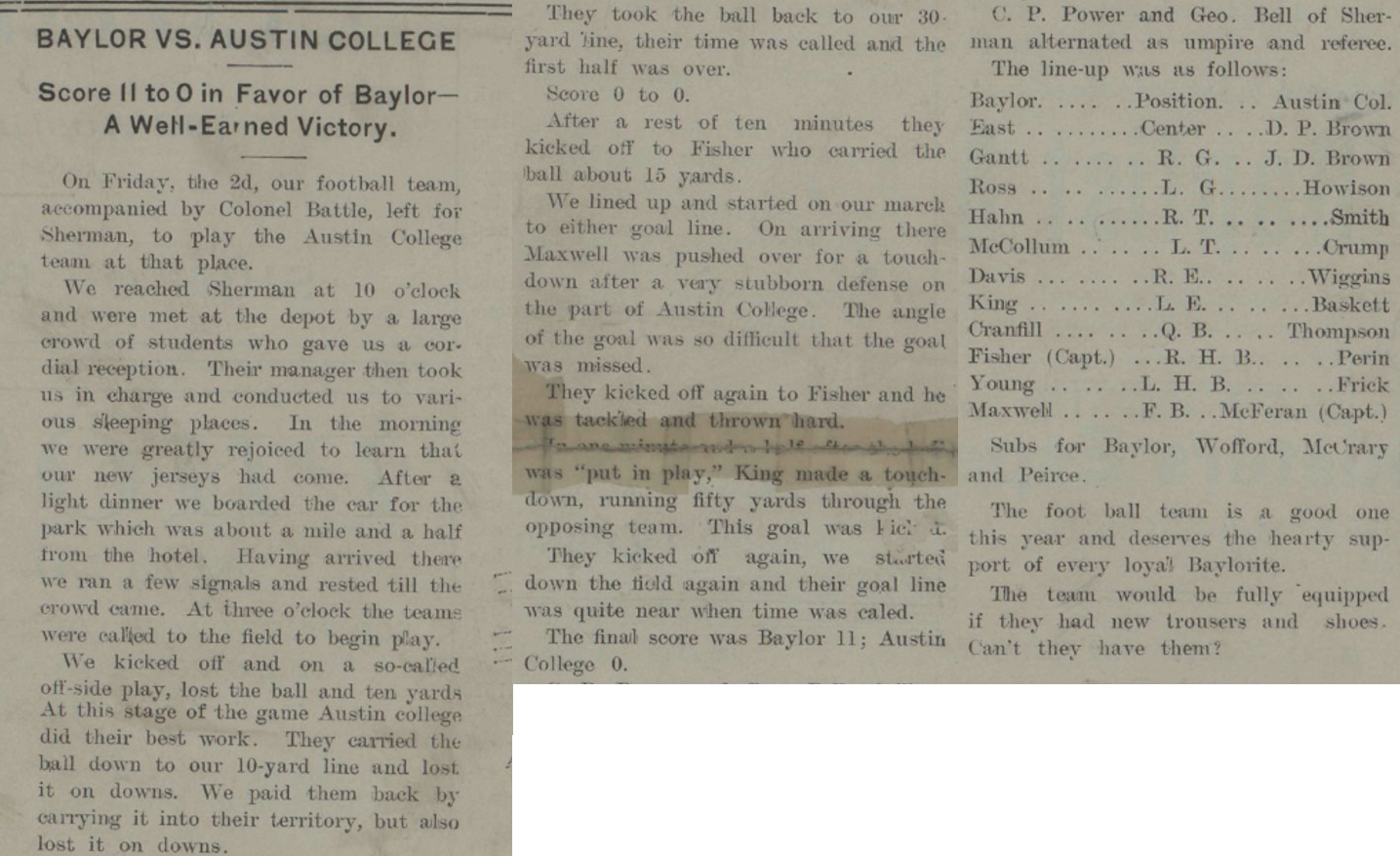

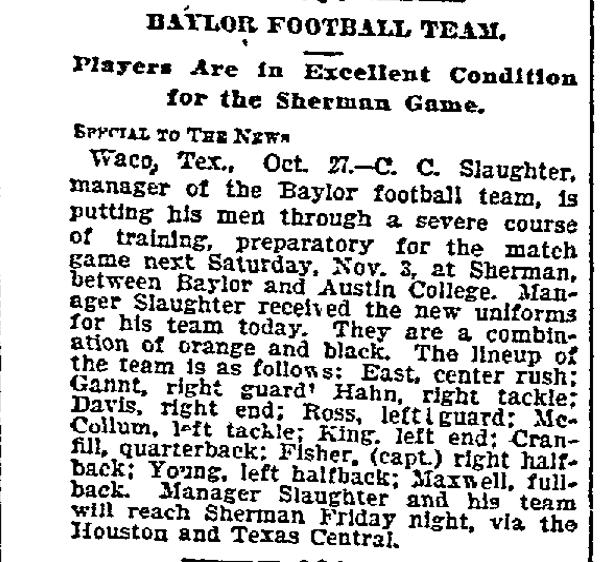

After a successful debut in 1899, Coach R. H. Hamilton began the search for opponents in 1900. The first matchup of the season was also Baylor’s first road game in its young history. The squad traveled north to Sherman to take on Austin College. The Dallas Morning News reported on October 28th that Coach Hamilton was “putting his men through a severe course of training, preparatory for the match game next Saturday, Nov. 3, at Sherman between Baylor and Austin College.”

Baylor reached Sherman on Friday night via the Houston and Texas Central rail. The next day, at Batsell’s Park just south of downtown, the Bears prevailed by a score of 11-0 in front of several hundred spectators. According to the News, “In the first half no score was made, but some pretty plays by Wiggins and Frick (of AC) enlivened the crowd into hearty cheers. In the second half……the teams lined up and went at it again furiously. King’s (of Baylor) magnificent run to fifty yards and ultimate score of a touchdown…. brought cheers from even those wearing the home colors.” AC’s quarterback during the game, Hoxie Thompson, has a Sherman Hall auditorium named in his honor.

The Baylor Lariat reported on the game as well:

“On Friday the 2nd, our football team…left for Sherman to play the Austin College team at that place. We reached Sherman at 10 o’clock and were met at the depot by a large crowd of students who gave us a cordial reception. After a light dinner we boarded the car for the park which was about a mile and a half from the hotel. Having arrived there we ran a few signals and rested till the crowd came. At three o’clock the teams were called to the field of play.”

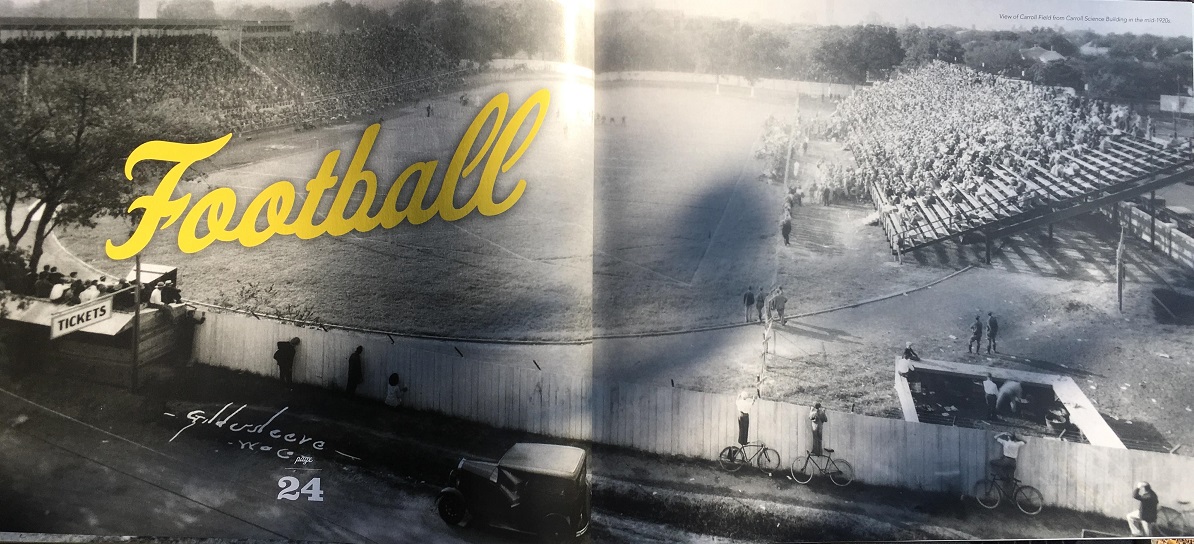

Chairman Lee Carroll, excited about the growth of the sport at Baylor, announced in 1901 that he would donate $1,000 to the school to build a new athletic field. Supplemented by funds from faculty and students, the new field was located just west of the Baylor administration building. It opened in 1902, in time for the season. It was named Carroll Field in honor of the first family of Baylor football, and it remained in use until 1936.

Baylor would face off 10 more times against Austin College after 1900, compiling a 5-4-1 record against the Kangaroos. The last meeting would be the most famous, when AC defeated the 1924 Southwest Conference champions in Waco.

As of 2018, Baylor has yet to request a rematch.

Tomorrow: Chapter 2: TCU 1896: Horned Frogs join the party

https://www.amazon.com/History-Baylor-Sports-Bear-Books/dp/1602584001/

The Birth of Texas College Football

Chapter 2: TCU 1896: Horned Frogs join the party

TCU’s move from Thorp Spring, TX to Waco, TX in 1895 coincided with an increased interest in college football by the student body. Students successfully petitioned for the creation of an official team in 1896, joining Texas, Texas A&M, and Austin College as the only Texas schools participating in the new sport.

TCU was originally named Add Ran college, after founders Addison and Randolph Clark. Addison had little patience for the frivolity of sport, and opposed its creation. That began to change in 1896, when his son Addison Jr. returned from the University of Michigan with an enthusiasm for the game. That year, the younger Clark teamed fellow student A.C. Easley to successfully win approval from administration for the creation of a football team.

With the decision, TCU became the fourth school in Texas to officially play the game.

Easley had just returned from a summer at the University Chicago, where he had witnessed the Maroons of Amos Alonzo Stagg. The two decided upon school colors for the team: purple and white. In December of 1896, TCU played its first game, defeating a local business college. Two games against a club team in Houston followed. The first season of TCU football came to a close with a record of 1-1-1.

In his book “Riff, Ram, Bah, Zoo! Football comes to TCU,” author Ezra Hood mentions the dramatic turnaround on campus in support of the game:

“Addison Clark had become so much a supporter of football, and athletics in general, that he argued in favor of intercollegiate play in other Texas cities before a skeptical board of trustees early that year. The board grudgingly added the ‘requirement of athletics exercises as a part of University courses.’”

TCU finished 1897 with a 3-1 record. The season included a win over Texas A&M; the sole loss was to the Longhorns in Austin. From Hood:

“Perhaps the success came from the team’s new mascot, the horned frog, a common lizard in central Texas before fire ants migrated to Texas in the 1950s and drove the horned frog away.”

Futility arrived for TCU over the next 7 seasons, as the Horned Frogs could only manage 3 wins over that time period. That began to change in 1905 with the arrival of Head Coach Emory Hyde, a Michigan man who had played under legendary coach Fielding Yost. Hyde’s first year ended at 4-4; it included two wins over rival Baylor, one over Trinity, and a victory in the first every meeting between TCU and Austin College.

On October 28, 1905, TCU journeyed to Sherman and met Austin College at Luckett Field (just north of campus). TCU dominated the game, pitching a 21-0 shutout. The Texas press mentioned the game right between Texas A&M’s rout of Baylor and Yale’s victory over West Point. The contest took place just one week after Texas A&M had manage to earn a tough 18-11 victory over AC at the same Luckett Field.

A fierce rivalry between TCU and AC emerged during the Austin College glory years. Between 1911 and 1923, Austin College went 5-6 against the Horned Frogs. One of those losses was bitterly disputed, and is the subject of a future TCU “Roo Tale”. The 1911 Roos, one of the best teams in school history, defeated TCU twice; the Horned Frogs were outscored 57-8 in those two losses. The 1923 Roos, also one of the best teams in school history, shutout the Frogs 27-0 on their way to a TIAA championship.

As the Roaring Twenties gave way to the Great Depression, TCU’s ambitions of joining and then dominating the Southwest Conference were realized. Games against AC continued, but were increasingly lopsided. The last occurred in 1933, when the defending SWC champion Horned Frogs traveled to Sherman to open their season. TCU won easily, 33-0. The TCU freshman team had yet to kick off their season, so they traveled to Sherman to support varsity. In the stands watching the Roos on the AC campus was the QB on the TCU freshman team. Slingin’ Sammy Baugh.

Nearly a quarter century earlier, the Roos had traveled to Waco on November 6, 1909 to face TCU. There, the Horned Frogs handed AC an 18-3 loss. TCU immediately began preparing for the following week’s contest against crosstown rival Baylor. On November 13, 1909, TCU beat the Bears 11-0.

It was another edition of the Baylor-TCU Revivalry. It was also the first Homecoming in American history.

Tomorrow, Chapter 3:

Austin College 1896: Kangaroos officially make it three

Roos who like TCU: Stephanie Loren Dawson, James Taylor, Weston Nowlin, Connor Welch, Connie Dees, Angie Scott, Bart Miller, Carl TheCoach Bailey, Jim Buie, Brittany F Smith, Taylor Penn, patrick conner, Bryan Katri, Art Clayton, Rodney Wellmann (Horned Frog & honorary Roo 😉

https://www.amazon.com/Riff-Ram-Bah-Football-Comes/dp/0875655661

The Birth of Texas College Football

Chapter 3: Austin College 1896: Kangaroos officially make it three

Field Day was an annual tradition alive and well at Austin College in the early 1890s. Students would gather on or around Thanksgiving holiday during the fall semester or early May in the spring to engage in all sorts of competition, from sack races and egg tossing to various foot races, track and field events, even baseball. Field Day had the sanction of Austin College administration and faculty. According to “Austin College: A Sesquicentennial History” by Dr. Light Cummins:

“…school policy advocated a wide range of intramural competitions that pitted student group against student group. Individuals were also encouraged to excel. It was at an annual field day that Austin College students first played a sport that had quickly become one of the school’s most important and enduring intercollegiate sports: football.”

The highlight of the November 28, 1895 Field Day was a football game. Students organized two teams to square off. Cummins again:

“This proved to be the most lively, spectacular, and popular event of the day. It drew over five hundred spectators, the largest number of person ever to attend an extra-curricular event at Austin College up to that time. In addition to townsfolk, parents, students, and their friends, most of the college faculty were also on hand to view the match. The sportsmanship of the players, along with the excitement manifested by the crowd, convinced President Luckett and key faculty detractors to reconsider their opposition to intercollegiate athletics.”

In early 1896, AC administration approved the creation of an official football team. Austin College would become the third school in the state to participate in the sports, behind Texas A&M and the University of Texas. Later that year, Democratic Presidential Candidate William Jennings Bryan fought the forces of austerity with his famous “Cross of Gold” speech at the party convention in Chicago. Do you like the movie the Wizard of Oz? Some suspect progressive Frank Baum’s story is an allegory of the election of 1896. Republican William McKinley defeated Bryan in the 1896 election that November, the same month as the official birth of AC football. Bryan, however, won 68% of the vote in Texas and easily took both Grayson and Brazos counties.

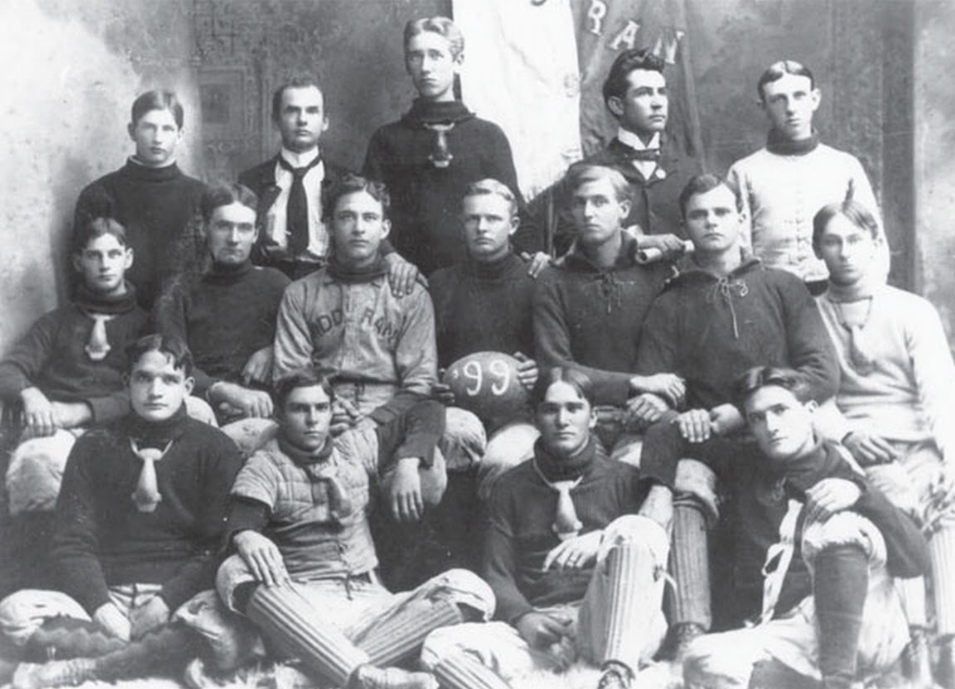

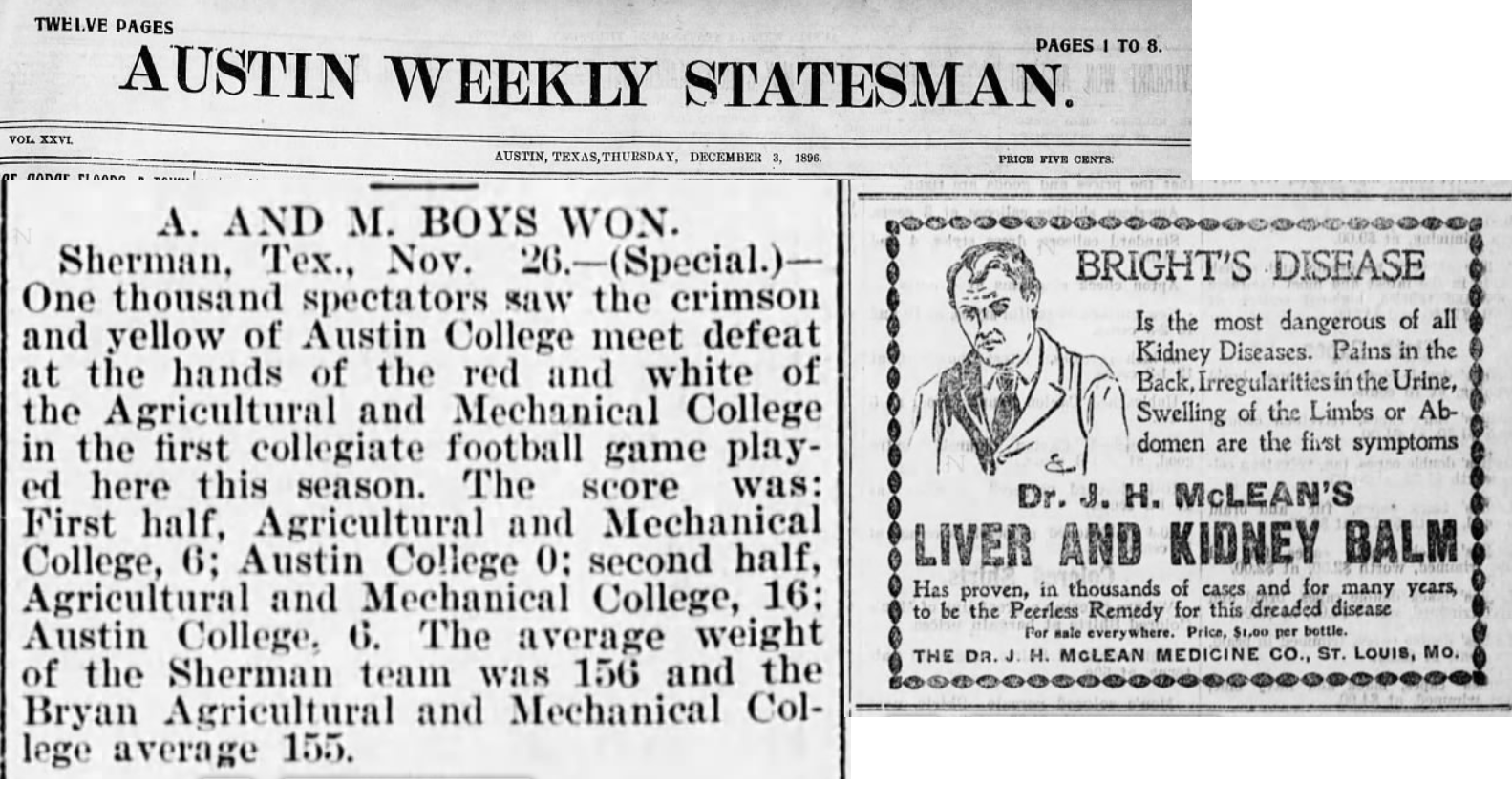

The ties between AC and Texas A&M run deep. Founded in 1876 and only 20 years old, A&M was, like Austin College, an all-male military institution in 1896. The Austin College student newspaper at the time was named “The Reveille;” the AC football team was referred to as “The Cadets.” It was only natural that AC would reach out to A&M to schedule the first ever football game, and it was not surprising that A&M accepted. The matchup would take place at Batsell’s Park in Sherman on Thanksgiving Day. November 27, 1896.

The day began with rain, but the sun soon broke out on a muddy field. Approximately 1,500 fans attended the event, most cheering for the hometown AC boys. Colorful hats, dresses, fine attire and tin horns were common sights. AC kept A&M close for the first half, and even scored in the second. But A&M eventually pulled away and won, 22-6. It was Texas A&M’s first victory over a collegiate opponent. It was also the first instance of a collegiate opponent finding the end zone against the A&M “Wrecking Crew” defense. The son of the first ever Austin College Kangaroo to score a touchdown would become Attorney General of the State of Texas 60 years later.

Because of student enthusiasm at the two schools, additional games were quickly scheduled against Texas A&M in both 1897 (in Sherman) and 1898 (in College Station). The Aggies won both contests, the second one by a score of 22-6 once again. That game, however, marked the first time that a collegiate opponent found the end zone in College Station. The game was played in a vacant lot not far from the A&M administration building. 115-year old Kyle Field had yet to be born.

By the end of the century, AC athletics had relocated to Luckett Field north of campus (corner of Lewis & Luckett). Batsell’s Park, located somewhere near the corner of Odneal & S. East St. in Sherman, is nothing more than a memory today.

Tomorrow, Chapter 4:

Texas A&M 1894: Aggies and the Thanksgiving Day rivalry

https://www.amazon.com/Years-Yards-Austin-College-Football/dp/B008FCOXYO

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_interpretations_of_The_Wonderful_Wizard_of_Oz

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2937766?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

The Birth of Texas College Football

Chapter 4: Texas A&M 1894: Aggies and the Thanksgiving Day rivalry

Texas A&M, Austin College, and the United States all share an important year: 1876. The nation celebrated its centennial that year, while 27-year old Austin College completed the move to its permanent home of Sherman, TX. Meanwhile, Texas A&M celebrated its founding, 7 years before the University of Texas.

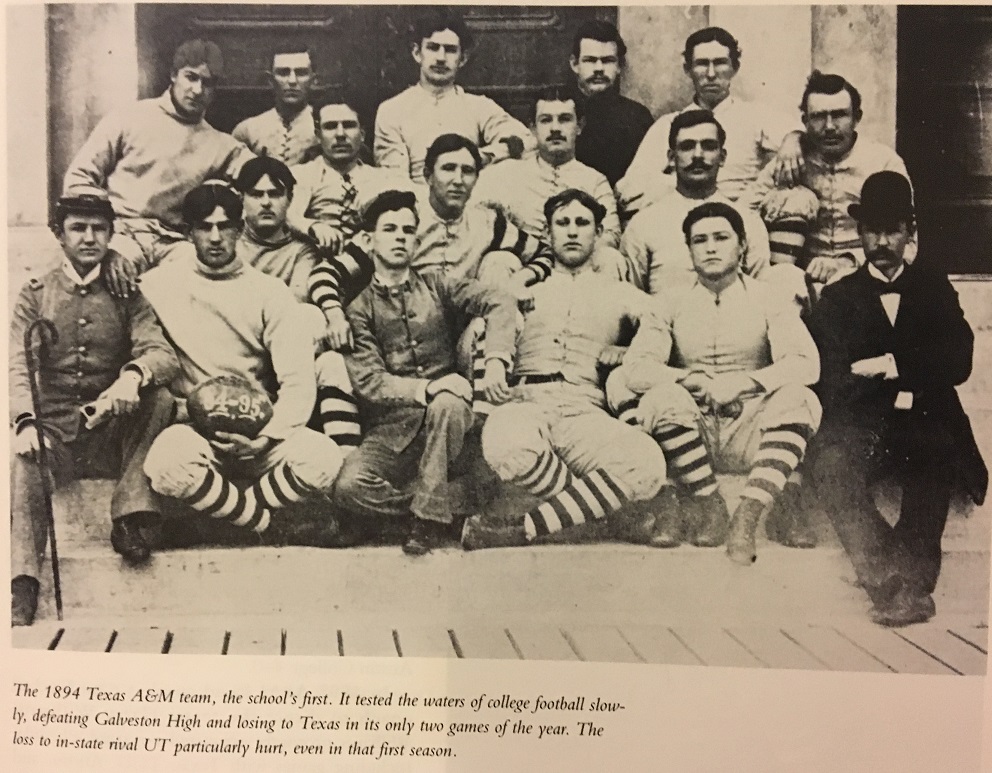

In 1893, word had already gotten around College Station. Those youngsters at “Varsity” in Austin had fielded a football team. Aggies became immediately determined do the same, and formed the first A&M squad one year later. With few colleges participating in the sport, the Aggies scheduled their first contest against Galveston Ball High School. A&M won going away in College Station, 14-6.

Flush with confidence, the Aggies immediately requested a game with the University of Texas, and traveled to Austin in late October. It was a mismatch. Aggie Milt Sims, a player who had spearheaded the effort to create the team, explained. From “100 Years of A&M Football,” by Gene Schoor:

“Well,” explained Sims, “Texas had a professional coach and they wore those big turtleneck sweaters, and when we got there and saw the size of those Texas players, I said to Mossenburg, ‘Mossey, if those SOB’s are as big as they look from across the field, God help us.”

UT won easily, 38-0.

Graduation, injury, and expulsion meant no A&M football in 1895, but the team was reborn in 1896 without UT. Instead of traveling to Austin, the Aggies accepted an invitation to journey to Sherman to take on Austin College on Thanksgiving Day. The 22-6 win was A&M’s first ever victory against a collegiate opponent.

Austin College and Texas A&M squared off on the gridiron 12 times between 1896 and 1917. No AC opponent was faced more frequently during that time span. An A&M win over AC in 1898 marked the first time a collegiate opponent scored in College Station. An 18-11 Aggie win in 1905 was marked by controversy; it was also the last Austin College-A&M game to be played in Sherman.

The Roos visited Kyle Field for the first time in 1909, and almost pulled off an upset in 1913. With one of its best teams in history, Austin College fell 6-0 at Kyle to a Charlie Moran Aggie team that was coming off of an 8-1 season.

That was as close as it would ever get.

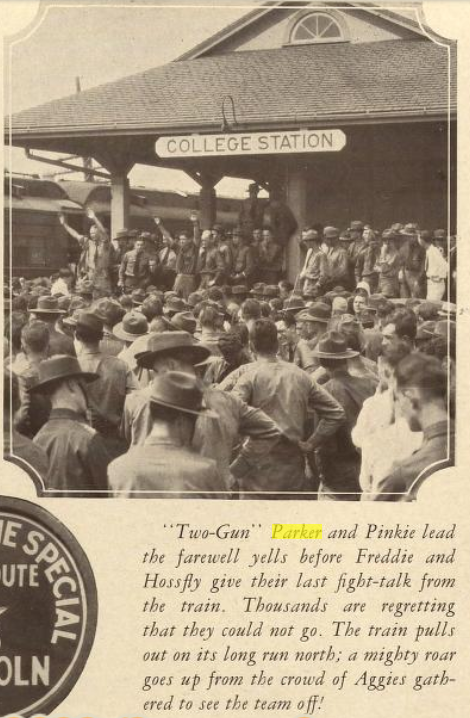

Texas A&M hired legendary coach Dana X. Bible in 1917. Bible’s Aggies went undefeated and unscored upon that year, earning an unclaimed national championship. They kicked off the season with a 66-0 win over Austin College. Unlike Baylor, a school which never ceases to keep up the Horns, Aggies, & Joneses, the Roos recognized the increasing disparity and ended the matchups forever.

It should come as no surprise that AC & A&M enjoyed such a close rivalry during the two-decade period after 1896. After all, both schools in the 1890s were all-male military institutions. Even the Austin College mascot “Kangaroo” comes from “Kangaroo Kourt,” an institution from the Sherman school’s military past.

The 1894 Aggie loss to UT was followed by one Texas victory after another. That first A&M win over the Horns finally came, in 1902. It ushered in one of collegiate sport’s greatest rivalries.

The UT-A&M rivalry is characterized by numerous periods. From the arrival of Charlie Moran in 1909 to Texas A&M’s national championship in 1939, the Horns and Aggies were deadlocked at 14-14-3. UT dominated the rivalry from 1940 to 1973, as the University of Texas grew substantially in the post WW2 period while A&M remained all-male and small. Texas A&M’s dramatic growth in the early 1970s, however, renewed the rivalry again. From 1974 to 2011, the Horns and Aggies were again deadlocked at 19-19.

The rivalry has since entered yet another period since 2011. It’s on life support. But vital signs remain. Let’s hope for a full recovery for this Texas institution sooner rather than later.

Tomorrow, Chapter 5:

Texas 1893: Longhorns and the Birth of Texas College Football

The Birth of Texas College Football

Chapter 5: Texas 1893: Longhorns and the Birth of Texas College Football

The Dallas Heavyweights were champions of the Texas football world.

It was a laborer’s game. Football was too rough for scholars at university, it was assumed. Even if a college were to field a team, the outcome would not be pleasant. In the early 1890s, football was dominated by working class teams from Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, Houston, & Galveston.

Year after year, the Heavyweights topped them all.

The game was spreading across the country, and was destined to eventually arrive at college campuses in Texas. It did, in the year 1893. The Great Panic of 1893 was devastating Wall Street, the Chicago World’s fair was gripping the nation, and the University of Texas officially established its first ever football team.

From “Long Live the Longhorns! 100 Years of Texas Football”, by John Maher & Kirk Bohls:

“The fathers of the football movement at UT were two brothers, Paul and Ray McLane, and James Morrison. Star fullback Addison Day later recalled, ‘I entered the University of Texas in September, 1893, and found Morrison and the two McLane boys had played football before, so we started out to get up two teams, which we did in almost no time.’”

The Heavyweights in Dallas received the news in Austin with interest.

From “Longhorn Football, An Illustrated History,” by Bobby Hawthorne:

“The Dallas football club billed itself as the ‘champions of Texas,’ and deservedly so. They were a thuggish bunch that cheated freely and often. Many of the other football clubs in Dallas refused to play them, so they constantly searched for new victims.”

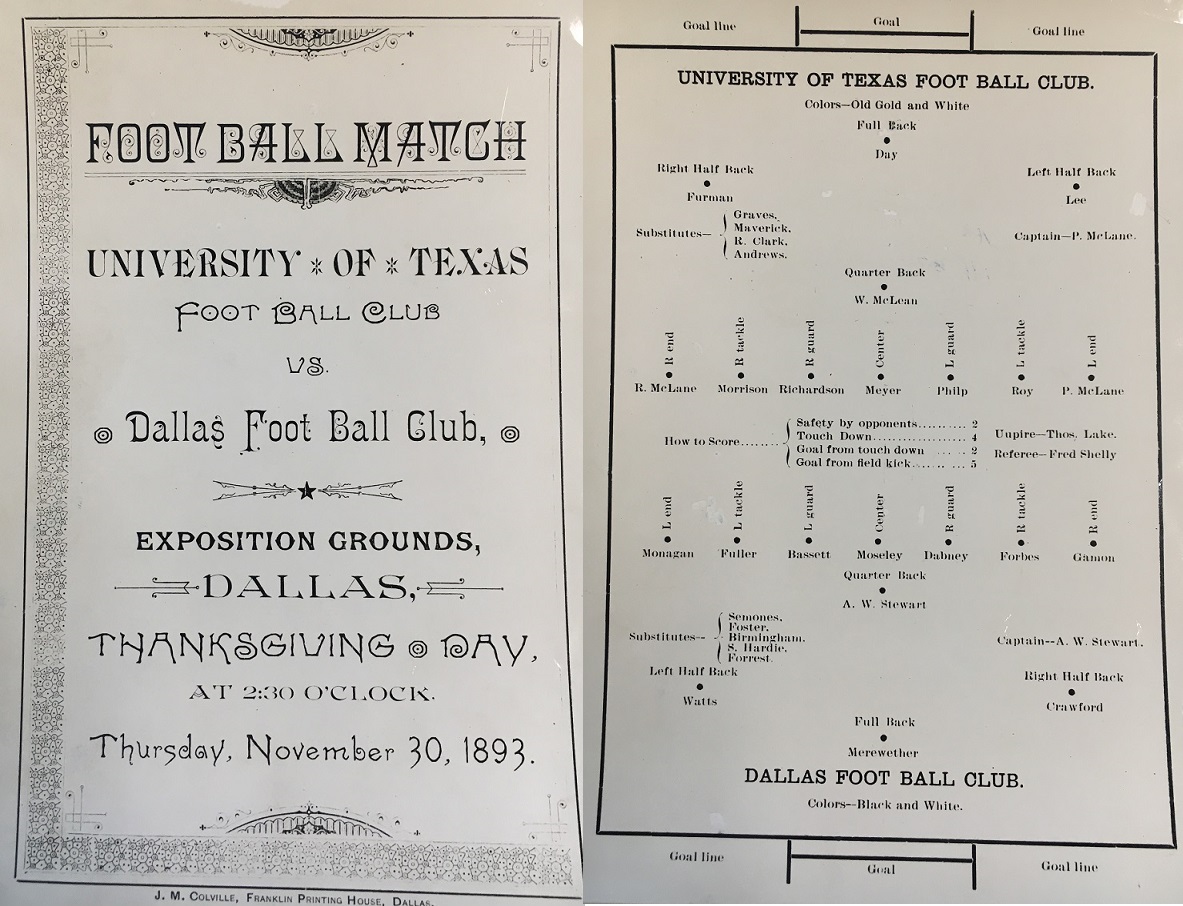

After defeating the Dallas YMCA football club in early November of 1893 at Fair Park, the Heavyweights offered an invitation to the University of Texas team for a game in Dallas. The game would take place in Fair Park, on Thanksgiving Day. November 30, 1893. The University of Texas accepted.

Thousands of fellow students, faculty, alumni, and Austin residents made the journey by rail to Dallas to support their boys. Waiting for them was the best team in Texas, alongside thousands of Heavyweights fans from the Dallas area. Most expected an easy win for the home team.

From “Long Live the Longhorns:”

“Dallas vs. Texas wasn’t just a game, it was an event. Dallas supporters wore the black and white colors of their team. The old gold and white, the Texas colors back then, were proudly displayed by the University’s fans at the fairgrounds.”

Texas received the ball first, and to the surprise of everyone marched right down the field and scored. The Heavyweights responded to each UT advance, and found themselves down just 12-10 at halftime. In the second half, the University boys found new life. They dominated on both sides of the ball; adding yet another touchdown in the process. A late score by Dallas cut the lead to 18-16, but by then it was too late. The final whistle sounded; “Varsity” had shocked the “Champions of Texas.”

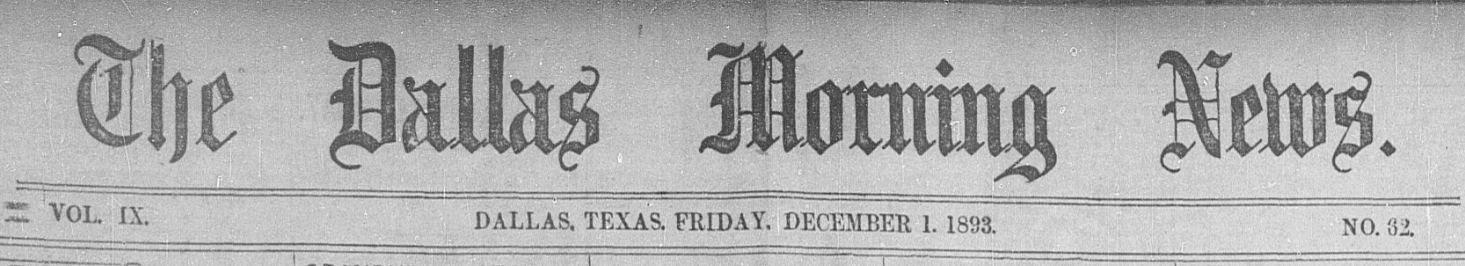

The Dallas Morning News gave extensive coverage to the game, devoting most of Page 2 to highlights of the game itself and its impact on the attendees and the state:

“It was the biggest football crowd ever assembled in Dallas. The grand stand at the fairgrounds was crowded with men and women, while the long line of carriages stretching around the inclosure were full, [while] the lawn in front of the stand….was a mass of men and boys who knew it all, who talked of Walter Camp…”

“The white and black of the Dallas eleven was everywhere fluttering, from the parasols of fair women and twisted in the button holes of the men. There were white and black flags, white and black ties, white and black dresses, [and] black hats with white bands. The varsity boys were not without friends. Besides the eleven they brought along with them a crowd of rooters, and these made the air hideous whenever their side scored.”

The Dallas Morning News seemed to understand the magnitude of UT’s win:

“This tale is of woe to Dallasites and bright to the Austinians. ‘Our name is pants and our glory has departed,’ said [UT’s} Tom Managan as he pulled his overcoat over his sweater yesterday afternoon, jerked his cap down over his eyes, ……and started for [his Austin] home by the unseen route.”

As the University of Texas football team began the long trip back to Austin, things had changed in the state of Texas. Football had arrived for good, college football was here to stay, and the University of Texas had become the “first” college in the state to play the game.

The Dallas Morning News also devoted ink on the same page 2 to other games around the country on that Thanksgiving Day of November 30th, 1893:

In New York, Princeton upset Yale 6-0 at the Polo Grounds in a game attended by over 40,000, the largest crowd to ever see a game in American history.

In Boston, Harvard dominated Penn, 26-4.

In South Bend, Notre Dame won 22-10 in a blinding snowstorm.

In San Francisco, Stanford and California tied 6-6 in second ever edition of the “Big Game.”

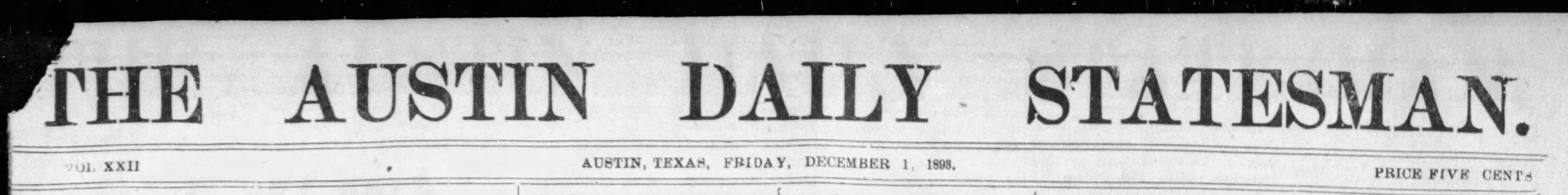

And in Sherman, TX, Austin College defeated Dallas YMCA by a score of 16-4.

.

.

.

Wait, What???

Tomorrow, Chapter 6:

Wait, What???

https://www.amazon.com/Longhorn-Football-Illustrated-Bobby-Hawthorne/dp/0292714467

https://www.amazon.com/Long-Live-Longhorns-Years-Football/dp/0312093284

The Birth of Texas College Football

Chapter 6: Wait, What???

In the early days of the fall of 1893, the Dallas Heavyweights football club had met the Dallas YMCA football team at Fair Park. As they often did, the Heavyweights won. After the win, the invitation by the Heavyweights to the Longhorn football team was extended. The game between the two Dallas teams was witnessed by a moderately sized crowd.

Turns out, there were Austin College Kangaroos in attendance.

Collegiate athletics spread like a wildfire across the South and Midwest in the 1880s; not surprisingly, Austin College was one of the first schools to catch an ember. From the foreword by Dr. Light Cummins in “100 Years, 100 Yards: The Story of Austin College Football:”

“College records indicate that students had been playing the game among themselves on the Sherman campus as early as the 1880s, although without the official sanction of the faculty or administration. In 1892, a group of students approached President Samuel M. Luckett with a proposal to play a football match in the name of Austin College with a team from the Dallas YMCA. Luckett consulted the faculty, who voiced strong disapproval of the game.”

“Although President Luckett and the faculty initially denied permission for the game in 1892, student persistence eventually triumphed the following year [1893] when the college reluctantly permitted them to play the Dallas team.”

Austin College administration’s decision did not officially sanction the sport on campus. It did, however, grant permission for the cadets to play in the name of Austin College. Permission in hand, the AC cadets traveled to Fair Park to watch the Heavyweights take on Dallas YMCA. After the game, and with full knowledge of the invitation extended to the Longhorns, Austin College invited Dallas YMCA to play a football game on the very same day: November 30, 1893. The game took place at Batsell’s Park in Sherman, TX; the park was located a half mile south of downtown along the main rail line, near the corner of Odneal & South 1st.

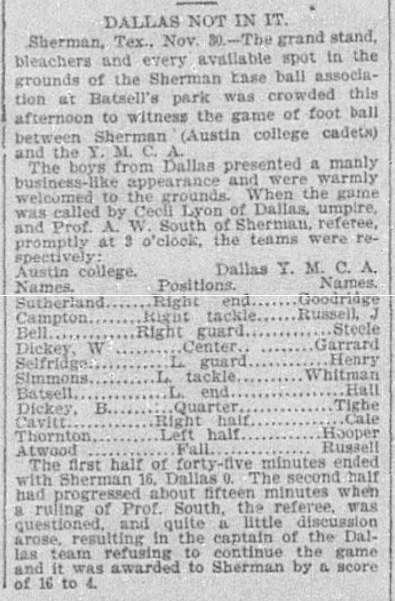

The Austin College game was reported in the Dallas Morning News on the same day and same page as the Longhorn victory at Fair Park. According to the News:

“The grand stand, bleachers, and every available spot in the grounds of the Sherman baseball association at Batsell’s Park was crowded this afternoon to witness the game of football between Sherman (Austin College cadets) and the Y.M.C.A.”

AC got off to a quick start, score 16 points in the first quarter. A Dallas YMCA touchdown in the 2nd quarter cut the lead to 12. Just before halftime, a dispute of unknown origin ended the game prematurely. AC Professor A.W. South, serving as referee, abruptly called the game after a resolution was not to be found. Austin College walked off the field with a 16-4 victory.

The game is briefly mentioned in the “100 Years, 100 Yards: The Story of Austin College Football” in the foreword by Dr. Light Cummins. While the 1893 team did not earn official faculty approval, the lack of sanction did “little to dampen student eagerness for the sport.” Two years later, football would finally win over the hearts and minds of AC administration.

“The popularity of football was apparent to everyone who attended the college’s annual athletic field day held on November 28, 1895. The most spectacular event of the day was a football match between two competing groups of Austin College Students. An estimated five hundred spectators watched an exhilarating game that stirred excitement to high levels of enthusiasm.”

Football would officially arrive at AC one year later.

Nevertheless, in spite of an AC administration’s less-than-complete blessing, Austin College was still playing the game on November 30, 1893 at the very same time as the University of Texas. One state, two colleges. One day, two football games. All of which leads to the most important question in this Roo Tale.

Which kickoff occurred first?

History provides the answer.

A program of the UT-Heavyweights game is a part of the Briscoe Center documentation accumulated for the Bohls/Maher “Long Live the Longhorns” book. It clearly shows a start time of 2:30 p.m. This is corroborated by the Dallas Morning News article itself, which states:

“At 2:20 o’clock there is a flutter on the grand stand. A lot of people clad very much like baseball players, only more so, with striped stockings and long hair march out into the field where a white line has been drawn.”

So, 2:30 it is.

Well, what about the AC / Dallas YMCA game?

From the same page of the same edition of the Dallas Morning News:

“When the game was called by……….Prof A.W. South of Sherman, referee, promptly at 3 o’clock, the teams were respectively……..”

By 3 o’clock, AC had already played nearly an entire half of football. By the time the Longhorn game kicked off at 2:30 in Dallas, Austin College was already battling in Sherman.

The Austin College kickoff occurred first.

Austin College: The birthplace of Texas college football.

Tomorrow, Chapter 7:

Austin College 1893: Kangaroos and the Birth of Texas College Football

The Birth of Texas College Football

Chapter 7: Austin College 1893: Kangaroos and the Birth of Texas College Football

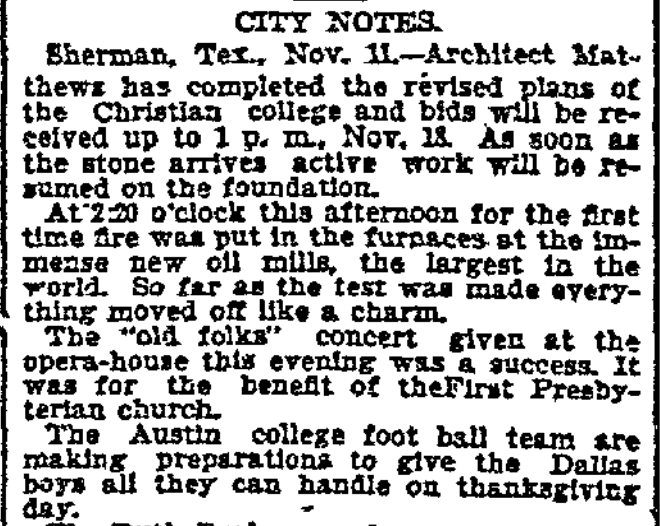

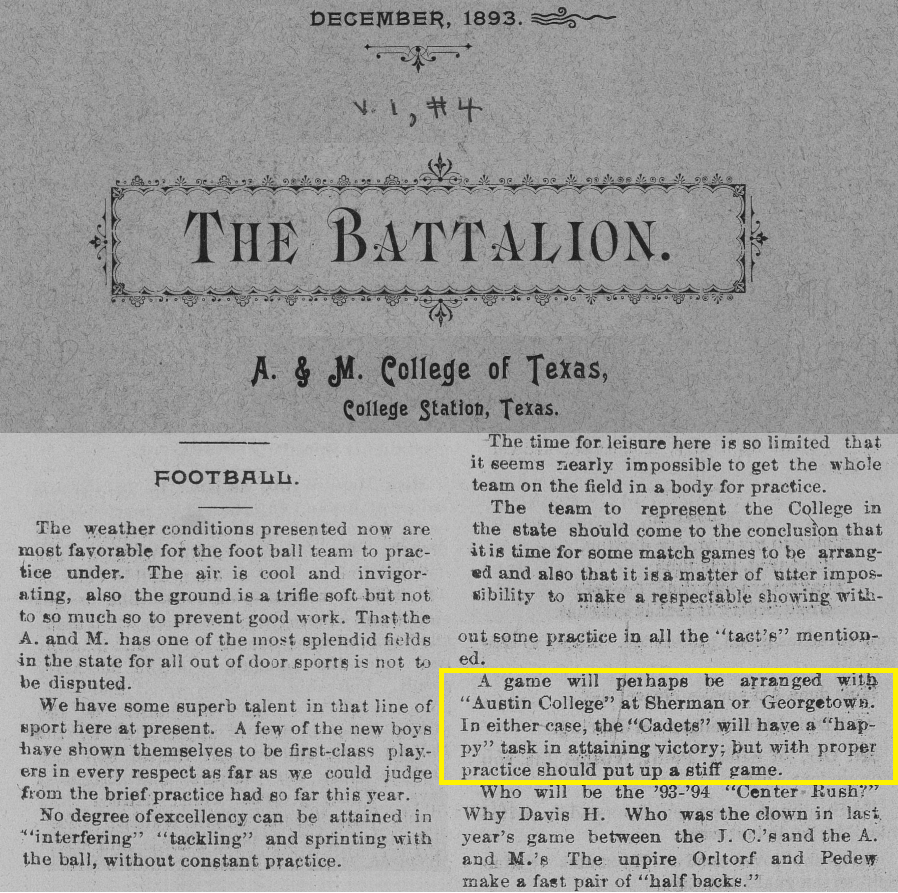

1893 was the first year when Texas A&M began to think seriously about the sport. In the December 1, 1893 edition of “The Battalion,” the same day as the Dallas Morning News and Austin Statesman reporting on the Austin College and University of Texas games, the Batt editor placed emphasis on A&M participating in the new game:

“The weather conditions presented now are most favorable for the football team to practice under. That the A. and M. has one of the most splendid fields in the state for all out of door sports is not to be disputed.”

“The team to represent the College in the state should come to the conclusion that it is time for some match games. A game will perhaps be arranged with Austin College at Sherman or Georgetown. In either case, the ‘Cadets’ will have a ‘happy’ task in attaining victory; but with proper practice should put up a stiff game.”

The Aggies would play in 1894, and eventually schedule that game with Austin College in 1896.

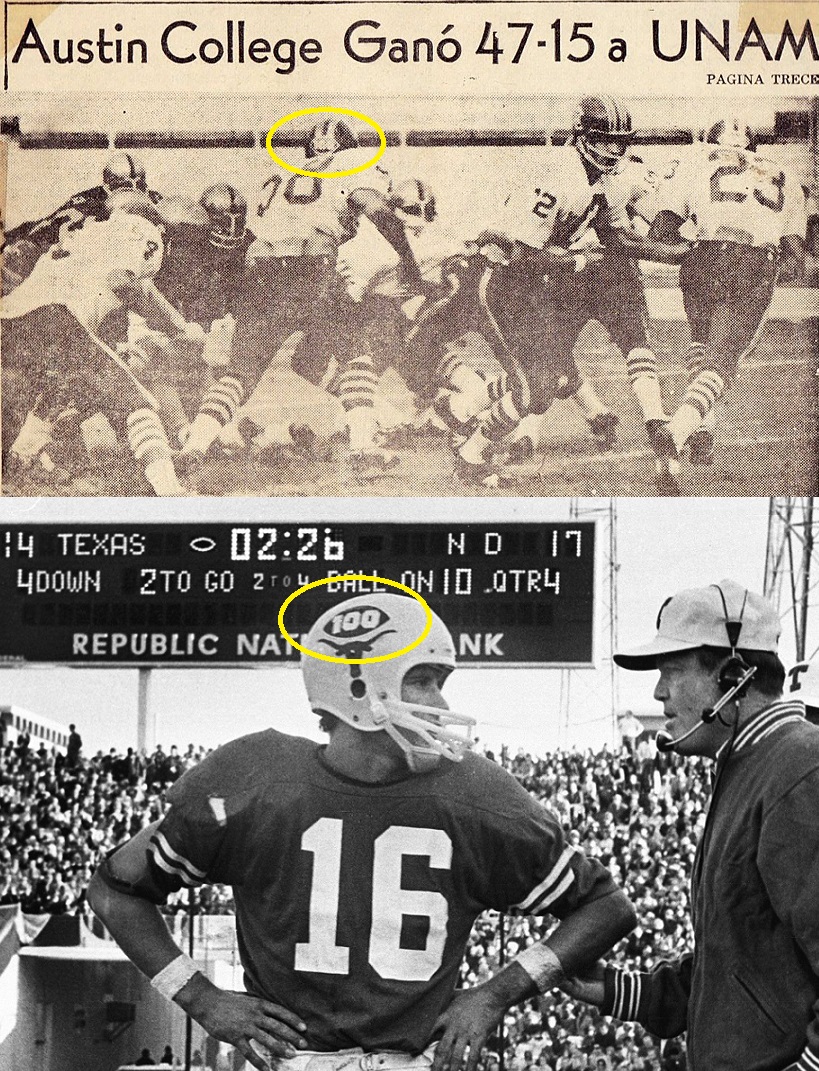

Austin College and the University of Texas both revere the past. During the 1969 season, Former OU Sooner QB Darryl Royal and the Longhorns wore the “100” patch on their helmets to commemorate the 100th anniversary of college football. Former SMU Mustang QB Duane Nutt and the Austin College Kangaroos did as well. The “100” patch can be seen in the 1969 UNAM game in Mexico City. AC & UT? They know their history.

Yet history is murky. It is debatable. It’s nuanced. It refuses to play nice.

Is Austin College the birthplace of Texas College football? It’s up for discussion. Unlike the UT team in 1893, the Austin College team did not yet have full official sanction. Jim Nicar, writer at the excellent site “The UT History Corner,” interestingly points out that the debate about which kickoff occurred first might hinge upon the definition of the word “called.” If that word denotes the “beginning” and not the “end” of the AC game, then the AC-Dallas kickoff occurred at 3pm, just after the UT-Dallas kickoff at 2:30.

Also, the Longhorns can point to their own unofficial scrimmages in the 1880s. See the comments. From “The UT History Corner:”

“In December 1883, less than three months after the University of Texas had formally opened, a group of UT students decided to have a football game. They might have been inspired by reports of the Thanksgiving Day contests back East. With no other team available, one of the would-be players – law student Yancey Lewis – arranged a match with the Bickler School, a private academy in downtown Austin. Lewis had been a tutor at Bickler before he enrolled at the University. In a week, both schools had to form teams, learn the rules, and practice. The game was held on a less-than-ideal patch of pasture land near the present day Blanton Museum of Art. No one on the field had actually seen a football game, and there certainly weren’t any refs available to enforce the rules. No matter. Both sides muddled through, though when it was over, the Bickler School was victorious, two goals to none.”

Documents about the Bickler school game itself, however, refer to kicking, leading one to suspect this game have had more in common with Rutgers/Princeton (descended from soccer) instead of Tufts/Harvard (descended from rugby, the ancestor of American football).

Is Austin College the birthplace of Texas College Football? Well, it just depends. In this sense, it’s similar to a different question:

Is Austin College, founded in 1849, the oldest college in Texas?

Baylor, founded in 1845, would dispute. Austin College claims to be the oldest college in Texas operating under an original charter. Baylor’s new charter adopted after AC’s birth is an (admittedly somewhat weak) argument for Austin College to claim the title.

Southwestern, founded in 1840, would also dispute. The foundation story of Southwestern, however, weakens its case. The school traces its founding to four earlier Methodist institutions, none of whom were affiliated with the school in Georgetown and none of whom existed in 1860 before the outbreak of civil war.

If we apply the “Southwestern rule” (ties to historic, defunct colleges of the same denomination) to determine the oldest, the story becomes even murkier. The oldest, now defunct denominational college in the state is San Augustine University in San Augustine, TX. Founded by Presbyterians in 1837, just one year after the Alamo, its existence would seem to strengthen AC’s argument.

However, the school in San Augustine was founded by the less traditional “Cumberland” branch of the Presbyterian church, allowing the Cumberland Presbyterians at Trinity University in San Antonio to claim the title. Well, we can’t have that now can we Dan Monson?

But why stop at the birth of the republic?

There were Catholic schools in Spanish Texas which could arguably claim the title. Native America educational entities before colonization could also make their case. Just when does an education become “higher education” anyhow?

As Dr. Light Cummins might say, history is murky. It is debatable. It’s nuanced. It refuses to play nice.

And yet, we can still say some things definitively.

In Texas, football is king. This sport, descended from rugby in England, made its way to the United States via a quirk of history in New England. From a game at Jarvis Field between Harvard and Tufts in 1875, it spread west like a wildfire and inevitably made its way to Texas.

In the early afternoon of Thanksgiving Day, 1893, Princeton & Yale were battling in New York in front of 40,000 fans. At the Polo Grounds in Manhattan, the game was being elevated into a national pastime. At that same moment down in Texas, the University of Texas Longhorns took the field for the first time in Dallas, giving official birth to the sport in the Lone Star State.

And Austin College was playing at the same time.

November 30, 2018 will mark the 125th anniversary of the birth of Texas college football. It’s likely you will read or hear about this “first” Longhorn football game in the weeks to come. When you do, be sure to point out to anyone listening. As the Longhorns were winning that first game, the Austin College Kangaroos were doing the same 60 miles north.

It’s not that a little school like Austin College wants or expects the glory that will inevitably be shined on the largest public university in the state. We understand our small role in Texas history compared to our much larger neighbor in Austin. But, we’re here. And we have something to say.

In the modified words of Tufts Coach Rocco “Rocky” Carzo:

“…politically, the Longhorns/Dallas Heavyweights game is right there. But just as the game changes, times change. We’ve got the evidence, and the point is, 125 years later, no one says it’s Austin College. Well, it is Austin College, and our family wants to be recognized.”

The Austin College family wants to be recognized.

And we’re not done! We’ve got a bonus chapter tomorrow:

Tomorrow, Epilogue: 100 Years of Austin College Football.

The Birth of Texas College Football

Epilogue: 100 Years of Austin College Football.

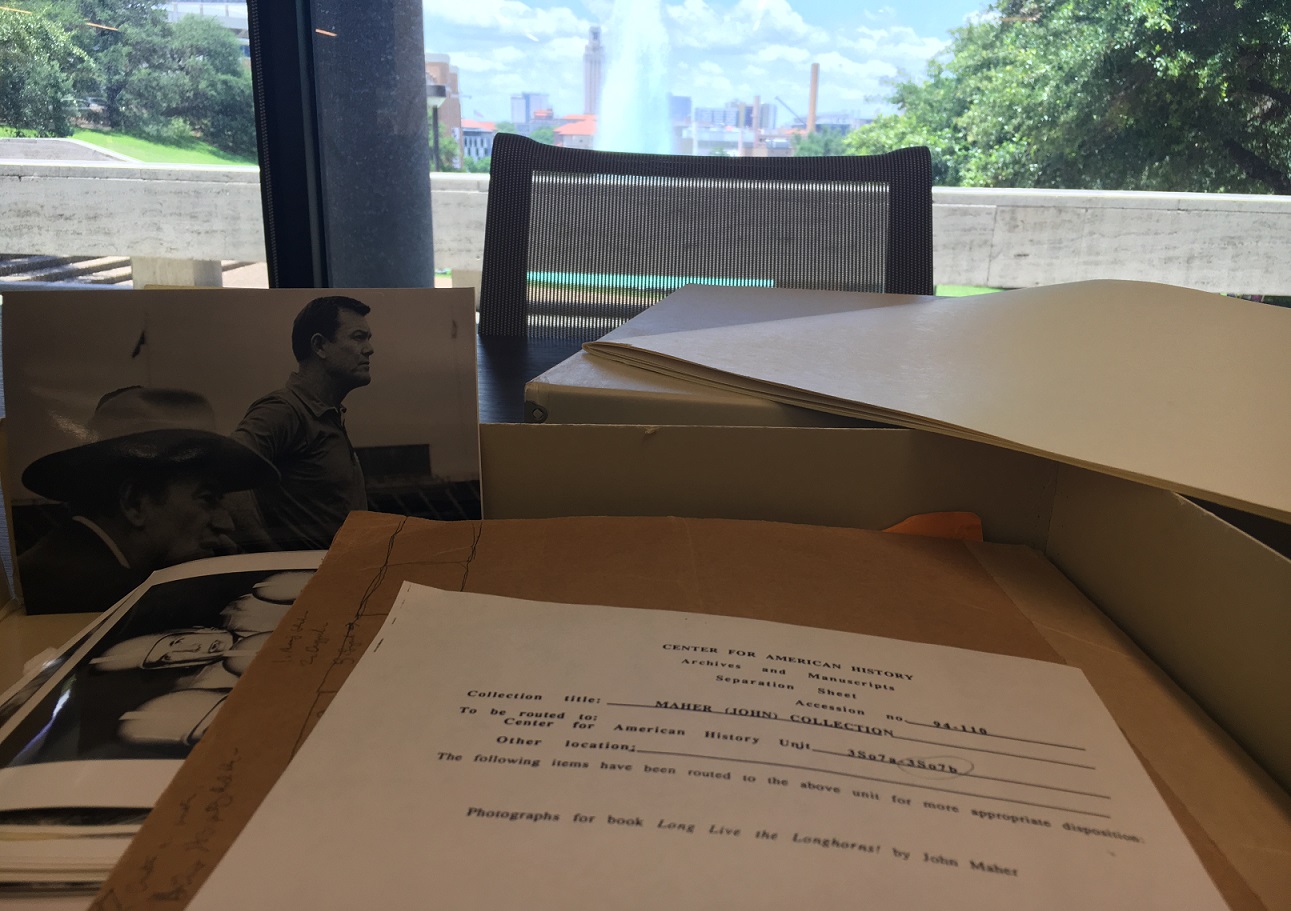

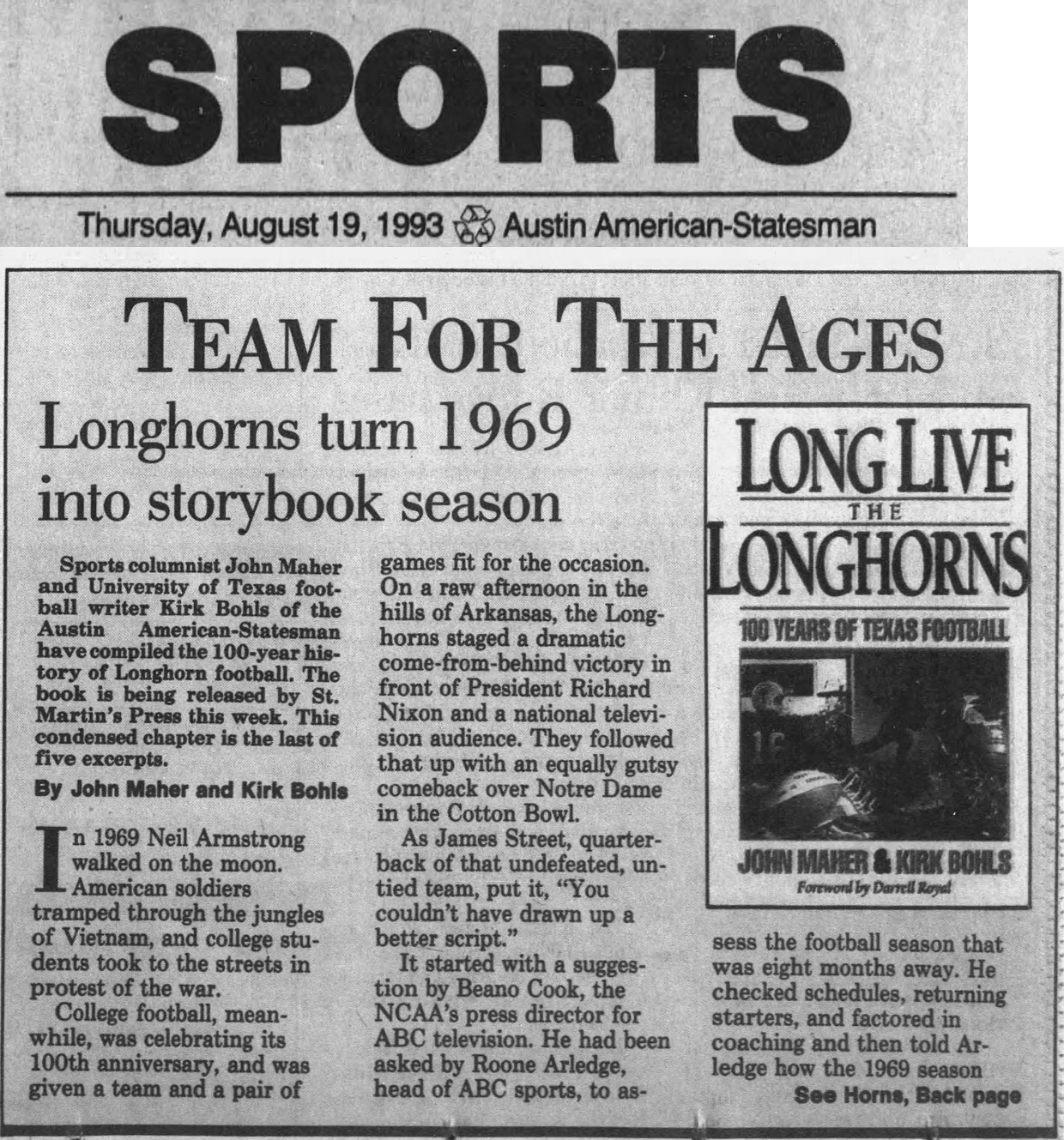

The Texas Longhorns celebrated the 100th anniversary of UT football in 1993. The season kicked off with the publication of “Long Live The Longhorns!” by Kirk Bohls and John Maher; it ended on Thanksgiving Day, just as it had in 1893. Texas A&M defeated the University of Texas in College Station to advance to the Cotton Bowl. The Aggies had the 50-yard line of Kyle Field marked with a football celebrating 100 years of the rivalry.

On September 18th of that year, UT opened the home portion of their season against Syracuse. The Longhorns kicked off at 2:30 p.m. at DKR Texas Memorial Stadium. 2:30 p.m., just as they had 100 years earlier in Dallas. It was the beginning of a second century of Texas Longhorn football.

And in Sherman, AC was already playing.

AC rival Trinity came to Sherman on September 18th, 1993. Barrett Jenkins caught two Brian Odom TD passes (h/t Shelley Odom), and Kirk Hughes hauled in a third. Rhett Box had over 100 yards rushing, and Ryan Nicholson picked off two passes. AC easily defeated its historical Presbyterian rival by a score of 31-0.

To mark the official 100-year football anniversary, Austin College published “100 Years, 100 yards: The Story of Austin College Football” in 1996. It’s a tremendous work by Willie Jacobs, the former “Voice of the Kangaroos,” with forwards by AC History Professors Dr. Edward Hake Phillips and Dr. Light Cummins. It’s been a great resource for my Roo Tales for years now.

I vaguely recall efforts to write the book in the 90s after I graduated. When I began to have interest in writing about Austin College back in 2015, I went about tracking it down. I had a copy transferred to a University of Texas library here in Austin. They called me to come pick it up, and I left the library with every intention of reading it at home. I began reading page 1 in the car.

The book was halfway finished before I even made it home.

Jacob’s work is full of detail and stories. Its research is well sourced, and the book was written in a pre-digital era when doing so was significantly more work. Jacobs passed away recently, and I’m grateful I was able to mention to his wife just how appreciated his work is before he passed. The book ends in 1996, the official 100th season of AC football.

But if 1996 is the official 100-year anniversary of Austin College football, then 1993…as this Roo Tale makes clear…is the unofficial 100-year anniversary. Inspired by Jacobs and his work, I’ve created a “100 Years of Austin College Football” video. It spans the years 1893 to 1993.

If you played for or studied at AC after 1993, you are not forgotten! While your years may not have fit within the 100-year theme of this Roo Tale, there will be story telling opportunities for more recent years in the future. Young Roos: enjoy this look at your past.

Art Clayton, a 1993 teammate of Kirk Hughes, made the season footage available online some time ago. I’ve borrowed footage from the 1993 AC win over Trinity, and have added it to photos taken over that century. Many of the photos come from “100 Years, 100 Yards.” Others come from AC Chromascope yearbooks. Still others were borrowed from newspapers and individuals. All of it has been put together in this tribute video, which documents the oldest* college in Texas and the first* college to play the sport.

*up for debate

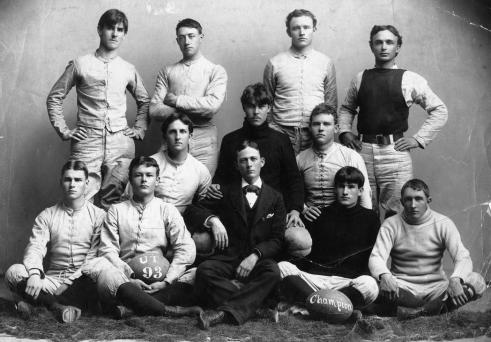

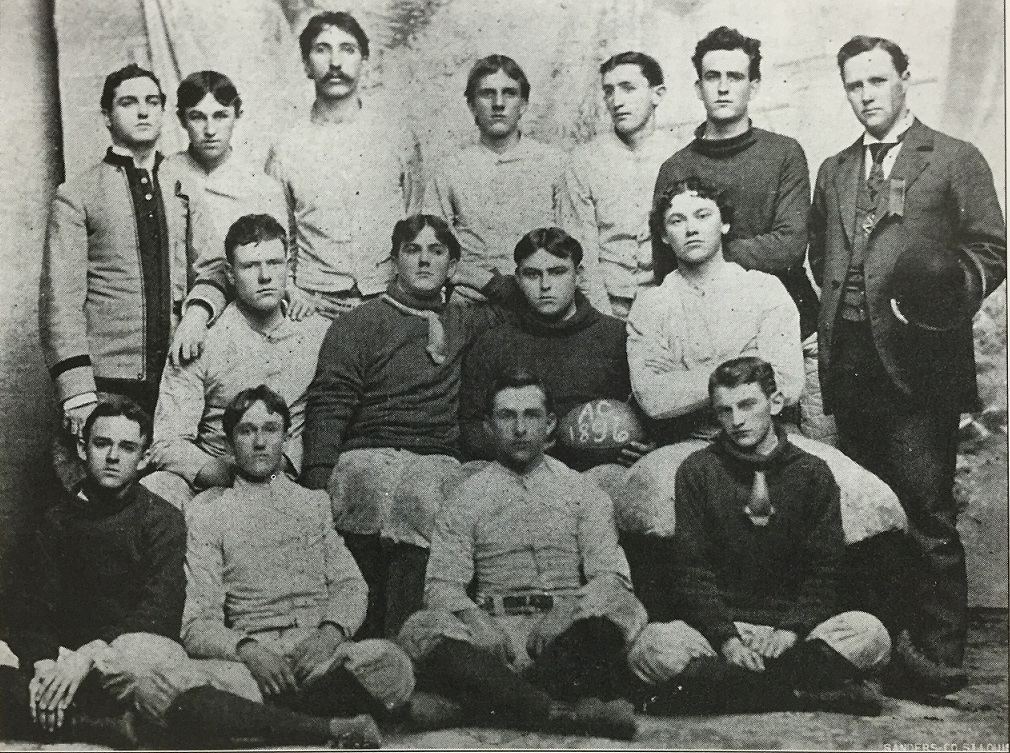

The 1893 Austin College Kangaroos:

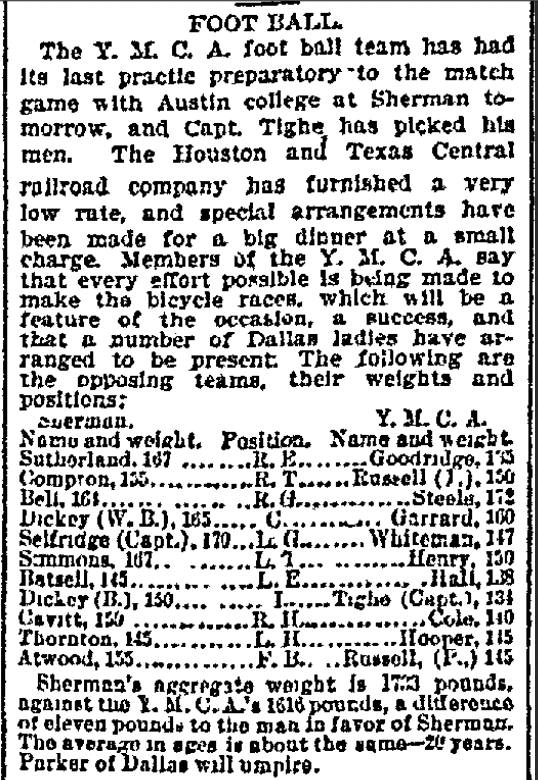

Sutherland, Compton, Bell, Dickey, Selfridge (Captain), Simmons, Batsell (he’ll come around again), Dickey, Cavitt, Thornton, Atwood

The 1993 Austin College Kangaroos (let me know who I missed):

Shane Allison, Brent Badger, Chris Bell, Nate Bostian, Rhett Box, Bruce Boykin, Matt Clark, Art Clayton, Clark Ericksen, DyShan Dunn, David Hall, Dusty Gray, Chris L. Grizzaffi, Max Hawsey, Kirk Hughes, Tyrone Johnson, Barrett Jenkins, Miles Maliska, Chris Melton, Brian Odom, Mike Olvera, Charles Owens, Ryan Nicholson, Raul Reyes, David Rapp, Marco Sanchez, Chris Sanders, Damon Price, Matt Richardson, Staley Shiller, Joey Staples, Jeff Tapp, Stephen Sullivan, Jason Sutherland, Lynn Varnell, Frank Vasquez, Kyle Warren, Randy Watson, Kevin Wilson, Dennis Womack, Rawleigh Williams, Lonnie Williams, Brandon Williams, George Harrison Jr

Hope you enjoyed this Roo Tale, as well as the 100-year video. We’ll see you for the next one.

https://www.amazon.com/Years-Yards-Austin-College-Football/dp/B008FCOXYO