On a trip back to Boston in 1993, I stopped by the Field of Dreams in Dyersville, Iowa. The film deals with many topics I love…. sport, loss, youth, fatherhood, even writing. I highly recommend a visit. People should visit, Ray, people should most definitely visit. 😉

Another season of baseball is nearly here. You’ve likely seen photos of ballplayers being shared on Facebook. Politics is important, but can be exhausting. We all need escapism, and baseball can provide. Stratford HS baseball kicks off another season today, and Coach Jason Willis offered to give me a ballplayer to post as others are doing. I asked him to give me an old timer and that I would try to link to Austin College. Jason gave me a pitcher for the Chicago White Sox.

This is the Roo Tale of Eddie Cicotte.

Chapter 1: If you build it, he will come

Cicotte made his major league debut with Detroit in 1905, and was traded to the Chicago White Sox in 1912. At Chicago, he became a star. He led the AL in winning percentage in 1916 and won 28 games in 1917. That same year, he tossed a no-hitter against the St. Louis Browns. And in 1919, he was close to notching 30 wins.

30 wins was a big deal. The salary owner Charles Comiskey paid Cicotte was $6,000, but Cicotte had a contract bonus of $10,000 if he were to hit that magic number of wins. Legend has it that as the regular season came to a close, and with Cicotte sitting on 29 wins, Comiskey benched his star pitcher for nearly a week to avoid having to pay the bonus. Cicotte was furious. So were the rest of his teammates.

The 1919 White Sox advanced to the World Series, but Cicotte, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and six others threw it in exchange for cash payments. The “Black Sox” scandal is the stuff of baseball lore, and it might never have happened if not for the injustice and greed of owners like Comiskey. Cicotte and the other members of the Eight Men Out were banned from baseball for life.

Cicotte had a teammate, however briefly, during the 1919 season. Austin College Kangaroo Charlie Robertson graduated in 1919, and was immediately signed by the White Sox. He pitched in a few games at Comiskey that year, before being sent to the minor league club in Minneapolis. From there, he watched the scandal unfold.

Read the Roo Tale of Charlie Robertson’s perfect game

Chapter 2: Ease his Pain

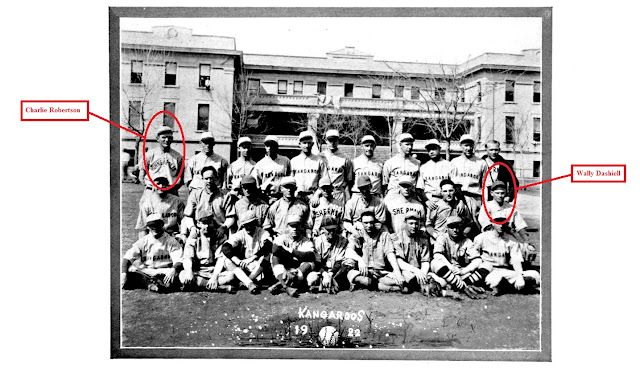

Robertson also never lost touch with AC. During the offseason, he’d return to Sherman to assist with football and winter baseball. He was back in the winter of 1922 to prepare Roo baseball for another season. See the team photo in front of Luckett Hall. Robertson is wearing his Minneapolis uniform, top row, far left.

Just a few months after this photo was taken, Robertson would be nationally famous. On April 30, 1922, he threw a perfect game against Ty Cobb and Detroit at Tiger Stadium. The feat would not be repeated until Don Larsen’s gem in the 1956 World Series. There were a number of fine Roo ball players in 1922, all pictured in the photo. But one of them has a special story. Wally Dashiell.

The Black Sox scandal players are immortalized in the movie Field of Dreams, and Eddie Cicotte is one. Played by actor Steve Eastin, Cicotte is the pitcher who faces Doc “Moonlight” Graham at the plate. Cicotte gives Graham a brushback pitch and puts him on the ground in one scene. Graham’s transgression? “He winked at me”, says Cicotte.

Steve Eastin as Eddie Cicotte in “Field of Dreams.”

Frank Whaley as Moonlight Graham in “Field of Dreams.”

A good portion of the movie focuses on Moonlight Graham. In 1905, this rookie was called up to the New York Giants for one game. He was inserted into the lineup in the ninth inning, but never made it past the on deck circle. The game ended, and Graham was sent down to the minors for the rest of his career. He never got to bat. In the movie, Graham’s dream is to face a big league pitcher.

After the brushback, Graham hits a long fly ball off of Cicotte to right field. The runner at third tags, and scores. This is actually a significant event in the movie. A sacrifice does not count as an at-bat in the record books. This is done to ensure that the batter is neither rewarded for an out nor penalized for an RBI. In this way, Graham achieves his dream of facing a major league pitcher without disturbing the sacred record books with an official at-bat. His contribution to the team is silent.

Chapter 3: Go the Distance

Wallace Dashiell graduated from Austin College in 1922, and like Robertson was also signed by Comiskey and the White Sox. Imagine his excitement. This Roo was headed to Chicago, to play alongside his former Roo coach, perfect game hurler, and now teammate. Dashiell spent 1923 in the minors, but was called up to Chicago to start the 1924 season. He watched Robertson pitch on a few outings, and patiently waited to get the call.

It came on April 20, 1924.

Dashiell was inserted at shortstop halfway through the game. His first two plate appearances were both strikeouts. The White Sox 8thinning began with the Cleveland Indians up 4-1. But a rally was about to get underway at Comiskey, and Dashiell would be a part of it.

Chicago closed the gap to 4-3, and had men on 1stand 2nd. Dashiell was called to sacrifice, and he delivered. The runners advanced, and would later score on a hit and squeeze play. Chicago won 5-4, and Dashiell was a contributor. As he left Comiskey that afternoon, his fellow Roo teammate Robertson probably slapped him on the back and muttered “fine job.”

Dashiell would never play in the majors again.

His career major league statistics: 3 plate appearances, 2 at-bats, 1 sacrifice hit, 0 hits/walks. One game.

He was Austin College’s Moonlight Graham.

After a few days, Dashiell was sent back down to the minors, where he began a successful 15 year playing career. He transitioned to manager in the 1930s and 1940s, and guided the Pensacola Flyers to numerous minor league pennants.

Chapter 4: Wanna Have a Catch?

Don Larsen’s 1956 perfect game renewed interest in Charlie Robertson’s feat for the White Sox. Robertson eventually retired to Texas, and passed in 1984. It’s unknown whether Robertson & Dasheill…..the two Roos of Luckett Hall & Comiskey…….remained close.

In real life, “Moonlight” Graham became a doctor and a pillar of the Chisholm, MN community. In a similar vein, Dashiell and family found a home in Pensacola. He managed the Flyers for many years, ran a small business, and was a beloved member of the city when he passed in 1972. Just this past year, the mayor of Pensacola declared August 22, 2016 as “Wally & Virginia Dashiell” day.

Like Shoeless Joe Jackson, Cicotte never played baseball in the majors again after the 1919 scandal. He went to work for Ford Motor Company, and was a Michigan strawberry farmer in retirement. He passed in 1965.

But just like the film, both Cicotte and Dashiell both probably had days where they dreamed of a field in Iowa to face off one last time. Cicotte, to continue what might have been. And Dashiell, what never was.

“Man, I did love this game. I’d have played for food money………. shoot, I’d have played for nothing.” – Shoeless Joe Jackson

“We just don’t recognize the most significant moments of our lives while they’re happening. Back then I thought, well, there’ll be other days. I didn’t realize that that was the only day.” – Moonlight Graham

“Wanna Have a Catch?” – Ray Kinsella

Good luck this season to Stratford HS. Go get ’em Coach Willis.